Military Triumph and Mistresses

Dr. Leen Kelchtermans

The Brussels painter Adam Frans Van der Meulen (1632-1690) created quite a furore at the court of the French King Louis XIV (1638-1715). He immortalised his military triumphs, embellished with the necessary pomp and bravado, as he did the royal couple’s entry in Douai, Northern France, in 1667. Van der Meulen actually depicted this event several times: at least three versions are known to date. The version in the collection of The Phoebus Foundation is without a doubt the most intriguing. For if you look closely, you will discover that the work not only includes the portraits of the king, his generals and his wife, but also … of his mistresses!

Entry in Douai

On 23 July 1667, Douai was honoured with a prestigious visit.((P.A. Plouvain, Souvenirs à l’usage des habitans de Douai ou Notes pour servir à l’histoire de cette ville, jusques et inclus l’année 1821, Douai, 1822: 386-387. I. Richefort, Adam-François Van der Meulen (1632-1690). Peintre flamand au service de Louis XIV, Antwerp, 2004: 224 mentions 30 August 1667. Sometimes 4 or 23 August 1667 is also mentioned, as in the online databases of the Musée du Louvre and the Château de Versailles. See https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010237037, [consulted on 06.02.2022]; http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#b3e9466e-c935-49a3-bc84-4976792fc90f, [consulted on 06.02.2022].)) The people flocked to the streets that were decked out in his honour. After it had been captured by the French army earlier that month, Louis XIV and Maria Theresia of Spain (1638-1683) paid the city a visit. Their marriage was nothing more than a business transaction. Maria Theresia was a good match: she was the daughter of the former enemy, the Spanish King Philip IV (1605-1665). When she married, she renounced her inheritance – which meant the Spanish territories would not belong to the French crown – in exchange for a dowry of 500 000 écus. However, the dowry was never paid. When his father-in-law died in 1665, Louis XIV was of the opinion that his wife had retained her inheritance rights, especially the right to the Spanish Netherlands. Moreover, Maria Theresia was the only surviving child from Philip IV’s first marriage. So, according to the devolution law that the Sun King liked to use to his advantage, devoid of nuance, she was the first heiress.((F. Lauwaerts, Het slagveld van Europa. De rol van de Spaanse Nederlanden in de internationale politiek van Engeland (1665-1668), master’s thesis, UGent, 2015-2016: 98-140.)) Since the Spaniards did not readily accept this claim, he launched a military campaign in May 1667, heralding the start of the so-called War of Devolution. The violence continued until the Treaty of Aachen was signed on 2 May 1668.

Louis XIV set off to the front with his entire court. His army defeated the weakened Spanish troops with ease. Important cities such as Courtrai, Tournai, Lille and Aalst fell into French hands. Douai, too, was occupied on 1 July 1667, and after just five days, was forced to surrender. As a charm offensive and to emphasise the fact that the conquered city belonged to the French crown ‘anyway’ through his marriage to the Spanish Maria Theresia, Louis XIV summoned his wife from Compiègne so they could pay an official visit to Douai. In his memoirs, the Sun King wrote of the irritation of the city leaders who felt they were given insufficient time to prepare for this important visit: ‘Je menais la Reine avec moi à dessein de la faire voir aux peuples des villes que je venais d’assujettir: de quoi ils se sentent tellement obligés qu’après avoir tout mis en usage pour la bien recevoir, ils témoignèrent encore qu’ils étaient fâchés de n’avoir pas eu plus de temps de s’y préparer.’((Richefort 2004: 224-225.))

Top job in Paris

Adam Frans Van der Meulen was the son of a Brussels notary who opted to become a painter. On 18 May 1646, he registered as a pupil of the battle painter Peter Snayers (1592-1667).((S. De Vries, ‘Adam-Frans van der Meulen (1632-1690), hofschilder van Lodewijk XIV, in de Republiek: 1672-1673’, Jaarboek Monumentenzorg (1990): 134-147; Richefort 2004; R. Wellington, ‘The Cartographic Origins of Adam Frans van der Meulen’s Marly Cycle’, Print Quarterly, 28, 2 (2011): 142-154, especially 144-145; L. Kelchtermans, Geschilderde gevechten, gekleurde verslagen. Een contextuele analyse van Peter Snayers’ (1592-1667) topografische strijdtaferelen voor de Habsburgse elite tussen herinnering en verheerlijking, 1, doctoral thesis, KU Leuven, 2013: 44. See also L. Starcky, Dessins de Van der Meulen et de son atelier, mus. cat., Paris, Mobilier national, 1988; À la gloire du roi: Van der Meulen, peintre des conquêtes de Louis XIV, exh. cat., Dijon, Musée des beaux-arts de Dijon, Luxemburg, Musée d’histoire de la ville de Luxembourg, 1998.)) He became Snayers’ apprentice when the latter was at the height of his career. Snayers became renowned for his large-scale topographical battle scenes in which he recorded the military feats of distinguished generals with great attention to detail. Van der Meulen’s style is very similar to that of his teacher. Five years later, in 1651, he himself became a master painter in the painters’ guild in Brussels. Van der Meulen’s talent was soon noticed abroad, for in 1664 he left his native city to settle in Paris at the request of Charles Le Brun (1619-1690). At the time, Le Brun was Louis XIV’s principal court painter, who glorified his patron through all manner of allegorical scenes or through depictions from Classical Antiquity. So when, in 1662-1664, the idea arose of designing an ambitious series of tapestries in which the Sun King was lauded by means of a detailed depiction of actual events, attracting the Brussels landscape and battle painter was a smart move.

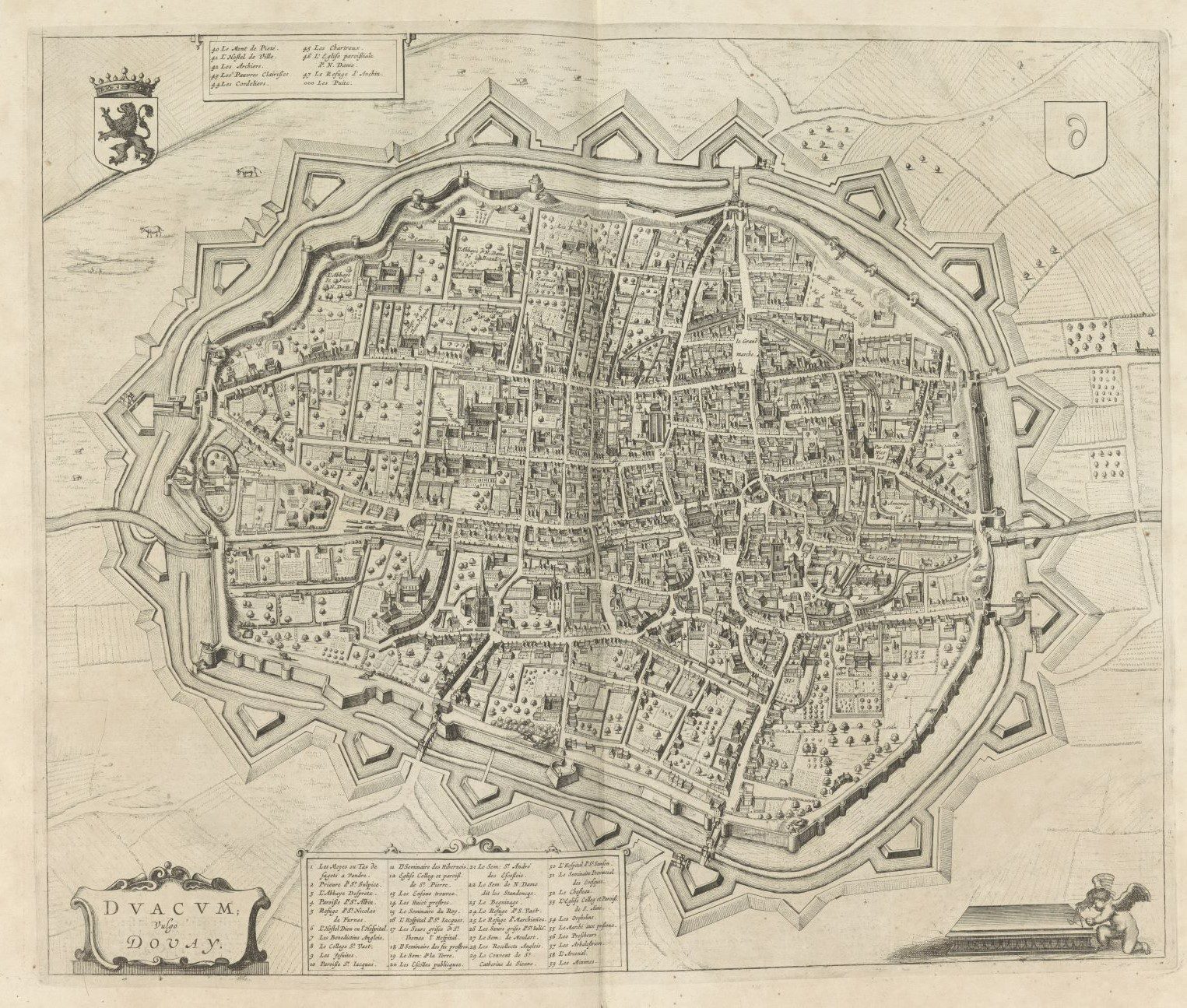

The series of tapestries was called L’Histoire du roi. The first edition consisted of fourteen tapestries, woven between 1665 and 1679 in the prestigious Manufacture Royale des Gobelins in Paris.((Richefort 2004: 73-83; J. Vittet, ‘[History of the King, cat. nos. 41-47]’, in: T.P. Campbell (ed.), Tapestry in the Baroque: Threads of Splendor, exh. cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Madrid, Palacio Real, 2007: 374-389, especially 374-384.)) They depict events that date from the King’s coronation in 1654 and the capture of Dole in 1668. They all highlight the Sun King’s military valour, diplomatic qualities and love of art. The War of Devolution was a vital component of this magnificent series. In preparation, Le Brun and Van der Meulen accompanied the King to the front. Van der Meulen’s approach differed from that of his teacher in this regard, as contemporary biographers indicate that Snayers never accompanied a campaign. Van der Meulen produced a considerable number of preliminary studies of the military events and of the conquered cities and their surroundings. A drawing of the French royal couple’s entry in Douai in July 1667 has also been preserved.(( For this drawing (inv. 27633), see https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl020213469, [consulted on 06.02.2022]. There is also another profile drawing of Douai that Van der Meulen produced in situ. Its viewpoint differs slightly from that of the painted versions. In the foreground, the figures are rendered very sketchy. The drawing is kept in the collection of the Mobilier national in Paris (inv. NO-90-000, paper, 410 x 230 mm), see https://collection.mobiliernational.culture.gouv.fr/objet/NO-90-000, [consulted on 06.02.2022].)) Van der Meulen produced the city’s profile in great detail. A comparison with the map of the city in Joannes Blaeu’s Novum ac magnum theatrum urbium Belgicae regiae (1652) shows that Van der Meulen depicted a view of the Porte d’Arras city gate. Le Brun drew the royal caravan in the foreground.

Since the entry in Douai was initially to be included in the L’Histoire du roi series, Van der Meulen made a modello or a small, preparatory oil sketch after that particular drawing, which is now located in the Château de Versailles (on long-term loan from the Musée du Louvre).((In total, Van der Meulen produced eight modelli for L’Histoire du Roi, including those depicting the sieges of Tournai and Douai. For the modello in the Musée du Louvre (inv. MV 5906), see https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010237037, [consulted on 06.02.2022]; http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#b3e9466e-c935-49a3-bc84-4976792fc90f, [consulted on 06.02.2022]; Richefort 2004: 79, 81, 224-225 (as a collaboration between Van der Meulen and Le Brun).)) The painted version only differs from the sketch with regard to minor details in the foreground. For example, the ladies in the carriage are wearing a scarf on their heads and their gaze is different from that in the painting. Van der Meulen’s modello formed the basis for a tapestry cartoon measuring no less than 352 by 580 cm, which was elaborated by Baudouin Yvart in the same period.((The cartoon is part of the collection of the Château de Versailles (inv. MV 2078), see http://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#29735b40-d543-4079-ad98-2b0aad966c53, [consulted on 06.02.2022].)) Four events related to the War of Devolution were eventually woven for the L’Histoire du Roi series: the sieges of Tournai, Douai, the capture of Lille and the defeat of the Count de Marsin. The king himself had taken part in these four military feats. Perhaps it was because he was not the only one who played a role in the entry in Douai, as he was accompanied by the queen, that he finally decided to remove the subject from the series. As a result, the cartoon was not woven.

Where’s Wally?

Although the scene of the royal entry in Douai was not included in the L’Histoire du Roi tapestry series, it was popular nonetheless. For Van der Meulen painted at least two other versions after the modello. There is the virtually identical representation, albeit somewhat larger in size, in the Musée de la Chartreuse in Douai,((For the version in the Musée de la Chartreuse (inv. 238, oil on canvas, 74 x 92 cm), see https://webmuseo.com/ws/musenor/app/collection/record/1393?vc=ePkH4LF7w6yelGA1CLiigvsIZ-I0NYZWj0QmJH3iUiY8m2FWvEaWBmg1tKEpenVPlC4TjEYCInMTymfQ_B2WmKcAqgB8U0uBIQg2DxbJALJTc08$, [consulted on 06.02.2022]. A very similar version was auctioned at Dorotheum on 12.05.2022 (lot 288, as the circle of Adam Frans Van der Meulen, oil on canvas, 65 x 82 cm). With thanks to Niels Schalley.)) and the version in the collection of The Phoebus Foundation. The design of the three works is the same, but remarkably, the faces of some of the horsemen and of the ladies in the carriage are much more detailed in The Phoebus Foundation’s painting. They are clearly individual portraits.((A visual analysis and an infrared reflectography image of the portraits on the canvas show that they are authentic and not overpainted or worked on at a later date. With thanks to Sven Van Dorst and Adri Verburg.))

First, there is the Sun King himself. Louis XIV can be recognised as the rider on the brown horse behind the royal carriage. He is dressed in a lavish cloak decorated with gold thread and his black hat sports red plumes. He looks in the direction of the spectator and holds the commander’s staff in one hand and the reins of his horse in the other. The latter is significant because, just as he controlled his steed, he ruled his people – and thus the newly captured city of Douai – as absolute monarch. While Van der Meulen depicts the king in the modello with a firm jawline, in The Phoebus Foundation’s version he paints a less idealised royal face. Louis XIV not only looks slightly older, but his cheeks are fuller, his nose plumper and he has a fine moustache on his upper lip. A comparison with Le Brun’s pastel drawing of the king from 1667 – the year of the entry in Douai – makes it clear that Van der Meulen depicted him more lifelike in The Phoebus Foundation’s version than in the modello. The horseman, who is also wearing a richly decorated cloak, portrayed astride a white horse, is probably Louis XIV’s brother, Philip ‘Monsieur’ d’Orléans (1640-1701). Monsieur’s luxuriant black curls and large nose can also be recognised in his portrait print by Antwerp-born Pieter Van Schuppen (1627-1702), who worked in Paris. The two brothers’ high rank can be deduced from the fact that they are the only ones wearing hats, whereas the others have taken them off out of respect. Another recognisable figure is Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, Viscount of Turenne (1611-1675), who played an important role in the campaign of 1667. He is the rider behind Monsieur, with dark sleek hair, a moustache and goatee. Pieter De Jode II’s print after Anselm Van Hulle’s portrait of the general confirms his identification. Between Louis XIV and his brother, Van der Meulen possibly depicted Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707), as a comparison with his portrait by the studio of François de Troy (1645-1730) suggests. This military engineer, whom Louis XIV held in high esteem, suffered a gunshot wound to the face during the fierce siege of Douai.((J.J.E. Roy, Histoire de Vauban, Lille, 1850: 40-41.)) De Troy’s portrait shows the scar on his left cheek. Did Van der Meulen want to hide his disfigured face by turning him towards the king so that only the right side of his face had to be visible?

In the stunning carriage, positioned in the centre of the scene, is the queen with her ladies-in-waiting. While the heads of the women in the modello are less detailed – the queen on the left is not easy to recognise and her companions are not particularly distinctive – this is not at all the case in The Phoebus Foundation’s version. The facial features of Maria Theresia, with her full cheeks, long nose and narrow mouth, as recorded in print by another Antwerp-born artist, Nicolaes Pitau I, in Paris in 1662, correspond to the severe-looking lady sitting in the carriage on the left. In the painting the leaders of Douai, dressed in black with a red sash over their shoulders, are kneeling in front of her out of respect.

What about the other ladies in the carriage? They are none other than the king’s mistresses! In front of the queen sits Louise-Françoise de La Baume Le Blanc de La Vallière (1644-1710), revealed by her printed portrait produced by Nicolas de Larmessin I in around 1667-1674. The similarities of her appearance, including her almond-shaped eyes, rather pointed chin and ringlets, are unmistakable in the two works. Van der Meulen may also have included her – albeit much less obviously – in the tapestry modello.

Louise de La Vallière was a lady of modest noble birth, who was hopelessly in love with Louis XIV and managed to win his heart as lady-in-waiting to his sister-in-law Henrietta Anne of England (1644-1670).((J. Lair, Louise de la Vallière et la jeunesse de Louis XIV d’après des documents inédits, Paris, 1881: especially 173-182; C. Hanken, ‘De koning en de dame. Over de ontwikkeling van de functie van de koninklijke maîtresse in Frankrijk (1444-1774)’, Amsterdams Sociologisch Tijdschrift, 19, 4 (1993): 70-78; A. Fraser, Love and Louis XIV. The Women in the Life of The Sun King, London, 2007: 67, 80, 84-97, 101-105.)) It was common knowledge that Louis XIV and his wife’s relationship was not very loving. Maria Theresia was never really accepted. She did not master French particularly well, was not interested in French fashion and dance culture, and was not exactly a great beauty. Louise de La Vallière, on the other hand, was gracious, sweet and obliging. Initially they kept their affair secret and when she became pregnant in 1663, De La Vallière moved to a country estate near the palace of Versailles. To improve her position, the king organised a grand festival in the summer of 1664, the eight-day spectacle Plaisirs de l’île enchanté, and appointed her maîtresse en titre. Thus De La Vallière became the Sun King’s first official mistress. From then on, the couple appeared in public together, although De La Vallière found it difficult to cope with the intense pressure and the piercing eyes that inevitably accompanied her status as the king’s ‘lover’.

Whereas nowadays extramarital adventures are usually conducted in the greatest secrecy, it was completely different at the court of Versailles.((Hanken 1993: 79-84.)) After all, Louis XIV had little to no privacy whatsoever. To anchor his autocratic rule, he had gathered the nobility around him and assigned them all kinds of positions within the cumbersome court etiquette that had to be followed at all costs. Its rules were based on the principle of inequality: one rank enjoyed more privileges than the other. Competition among the nobility was cut-throat: they all strived for the king’s favour and coveted a higher position. Everyone with whom the Sun King spoke – and everyone with whom he did not – every glance, every gesture, was closely observed. However stifling, this set-up ensured that Louis XIV was firmly in control. His mistress was – to a far greater extent than the queen – his confidante, for she knew everyone at court and was extremely loyal. After all, she owed her distinguished but precariously insecure status solely to the monarch.

Therefore, De La Vallière’s official title afforded her protection and a certain prestige. The children she had with Louis XIV were recognised and, before the king left on the military campaign of May 1667, he appointed her – for her security and out of his love for her, or as he wrote in his memoirs: ‘convenable à l’affection que j’avois pour elle depuis six ans’ – Duchess of Vaujours.((A. Chéruel, Mémoires de Mlle de Montpensier, petite-fille de Henri IV, collationnés sur le manuscrit autographe avec notes biographiques et historiques, 4, Paris, 1859: 47, note 1.)) But the court interpreted it as a subtle hint: their affair had almost run its course. Impulsively and against the King’s orders, the heavily pregnant De La Vallière travelled after her lover on her own initiative, much to the irritation of Maria Theresia. The queen was so distraught upon her arrival that Louis XIV’s niece Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, better known as Mademoiselle de Montpensier (1627-1693), wrote about the event in her memoirs: ‘Je trouvai la reine qui pleuroit, qui avoit vomi, qui se trouvoit mal.’((Chéruel 1859: 49; Fraser 2007: 134-137.))

Yet, it was during that very campaign that Louise de La Vallière lost her privileged position. The king became increasingly interested in the beautiful, flamboyant, lover of art Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart-Mortemart, Marquise de Montespan (1641-1707).(( Chéruel 1859: 490; Fraser 2007: 124-133, 200.)) After her impoverished husband had opted for a military career and left her with two young children, she set her sights on a career as a lady-in-waiting to Maria Theresia; the two women got on famously. The next step was to win over the king and she succeeded in this endeavour during the campaign of 1667. According to Mademoiselle de Montpensier, she stayed in one of the rooms ‘qui étoient proche de la chambre du roi’ and he often saw the marquise ‘à ce que l’on disoit, à sa chambre.’((Chéruel 1859: 50, 52.)) She also recalled the predicament she suddenly found herself in when, at one of the dinners, the queen complained about the fact that the king did not go to sleep until four in the morning and asked her ‘à quoi il peut s’amuser.’ The king defended himself – rather feebly – by saying that he had been going through the mail and answering letters. ‘Il sourit, et pour qu’elle ne le vît pas, tournoit la tête de mon coté. J’avois bien envie d’en faire autant; mais je ne levai pas les yeux de dessus mon assiette.’((Chéruel 1859: 52.)) There was another uncomfortable evening worth mentioning in early August. The queen started talking about a letter she had received in the presence of the Marquise de Montespan (!): ‘J’ai reçu hier une lettre qui m’apprend bien des [choses], mais que je ne crois pas. On me donne avis que le roi est amoureux de Madame de Montespan et qu’il n’aimoit plus La Vallière.’((Chéruel 1859: 58.)) The naive Maria Theresia ignored the advice and continued to believe, unjustly, in the innocence of her renegade lady-in-waiting. The facial features of the lady on the right in the carriage in Van der Meulen’s painting in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection – such as her round face, arched eyebrows and large eyes – are extremely similar to those in surviving portraits of the Marquise de Montespan, such as the one from Pierre de Mignard’s studio dating back to the last quarter of the seventeenth century. It is no coincidence that the lady who can be identified as Louise de La Vallière is looking (angrily or wistfully perhaps?) at her successor.

In her memoirs, Mademoiselle de Montpensier recounts that the king, after Louise de La Vallière’s unexpected arrival at the front, ordered that she and the queen go to church in the same carriage in an attempt to calm the tension between the two ladies. ‘Le lendemain elle [Madame de La Vallière] vint à la messe avec la reine; quoique le carosse fût plein, on se pressa pour lui faire place, et elle dina avec la reine.’((Chéruel 1859: 50; Fraser 2007: 136.)) This probably took place in Avesnes between 9 and 14 June 1667. It is also likely that the Marquise de Montespan, as Maria Theresia’s lady-in-waiting, would have done the same on several occasions. Yet it is unclear whether the three love rivals actually shared a carriage during the official entry in Douai. This is not so important in itself, because what really counts is that the main characters involved in the royal love saga can be identified. As in his battle scenes – and similar to other battle painters – Van der Meulen always depicted the topographical setting with great accuracy, but sometimes he brought together events that took place at different times in the same painting.((De Vries 1990: 135.))

Who for?

It is not known for whom Van der Meulen produced The Phoebus Foundation’s fascinating painting.((The painting’s provenance only dates back to 1968.)) However, it must have been intended for someone at court, who would immediately recognise the portraits of the king, his generals and the ladies in the carriage, and who could recount the juicy stories right down to the last detail. Perhaps Van der Meulen painted it for Mademoiselle de Montpensier. As her memoirs reveal, she knew the intrigues of the court like no other. Moreover, she was very fond of Van der Meulen. She became his son Louis’ godmother in 1669 and ordered smaller versions of almost all the paintings he produced for the king – including the modelli for L’Histoire du roi – to decorate her country house near Choisy. In her memoirs, she wrote:

‘Le Petit Cabinet est orné de conquêtes du roi peintes par Van der Meulen, un des plus habiles peintres de ces manières. Les sièges, les combats, les occasions y sont écrites, afin que l’on sache ce que c’est. On y connaît le roi partout, il est fort bien peint, il est sur la cheminée à cheval. Il n’y a rien à dire sinon que le Cabinet est trop petit, il y aurait encore bien des actions à y ajouter; je trouverai des places ailleurs pour avoir la joie de voir les grandes actions qu’il a faites, et qu’il continuera à faire.’((Richefort 2004: 124-130, quotation on p. 127.))

The inventory of the estate of Anne de Souvré, the Marquise of Louvois, who later acquired the residence, mentioned that it still housed twenty paintings by Van der Meulen in 1715, including ‘La ville de Douai’. It is currently impossible to prove with certainty whether it is the siege, or the entry in the city, or whether it is the version in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection. But one thing we can be sure of is that Mademoiselle de Montpensier would have delighted in the lively portraits.

Details create the bigger picture

In autumn 1667, Louise de La Vallière gave birth to Louis XIV’s fourth child in Paris. She left the court and became a nun. Marquise de Montespan continued to be the king’s official mistress for another fifteen years and bore him six children. She enjoyed the attention and her privileged position until she herself was toppled from her dubious throne by Françoise d’Aubigné, Marquise de Maintenon in 1682. Maria Theresia remained queen until her sudden death in 1683. On her deathbed, she is reported to have said that she had only been happy for one day since her marriage.((‘Depuis que je suis Reine, je n’ai eu qu’un seul jour heureux.’ Fragmens de lettres originales De Madame Charlotte-Elizabeth de Bavière, Veuve de Monsieur, Frère unique de Louis XIV, Ecrites à S.A.S. Monseigneur le Duc Antoine-Ulric de B** W****, & à S.A.R. Madame la Princesse de Galles, Caroline, née Princesse d’Anspach, 1, Hamburg, 1788: 15.)) She did not specify which day she meant. It was probably not 23 July 1667. During that hot summer, her husband conquered major cities that were part of her father’s empire and she was painfully reminded of her unhappy marriage. Her husband’s pregnant mistress, maîtresse en titre Louise de La Vallière, had the audacity to join the military campaign uninvited, in which she was afforded a prominent role through entries as the French queen and Spanish heiress. Her beloved lady-in-waiting, the Marquise de Montespan, also betrayed her shamelessly by secretly sharing her bed with the king at the time. Adam Frans Van der Meulen subtly incorporated all this drama into his intriguing version of the French royal couple’s entry in Douai in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection. The master conveys his skill in the smallest of details. Because if you look closely and are privy to the rumours, he makes it perfectly clear that during the military campaign of 1667, it was not only the French troops who were fighting for the Spanish Netherlands, but also the three ladies in the carriage who were fighting for the Sun King’s heart.

How to cite this item?

L. Kelchtermans, ‘Military Triumph and Mistresses’, Phoebus Findings, https://phoebusfoundation.org/phoebus_findings/3/, accessed on [dd.mm.yyyy].

All rights reserved. No part of this Phoebus Finding may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from The Phoebus Foundation. If you have comments or want to make use of our images, we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: info@phoebusfoundation.org