From Mary Magdalene to the Virgin Mary. A Glimpse Underneath the Paint Layers of an Eighteenth-Century Our Lady of the Candelaria

Carlos González Juste

Mid-June 2024, the exhibition History and Mystery: Latin American Art and Europe opens at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, Estonia and will feature more than a hundred Latin American artworks from The Phoebus Foundation’s collection. In preparation for this project, a large-scale conservation and restoration programme was launched in The Phoebus Foundation’s restoration studio to conduct in-depth research into the selected works. Our Lady of the Candelaria, an eighteenth-century oil painting from the ‘Cuzco school’, was also included. This Phoebus Finding focuses on the fascinating results of that research.

Virgin mother conceived without sin

The depiction of Our Lady of the Candelaria is based on the story of the apparition of Mary to two shepherds on the island of Tenerife in 1392. They found a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary bearing a candle in her left hand and the Christ Child with two doves in the other.1 Because of the key role played by Tenerife and the other Canary Islands in maritime trade between Spain and the Americas (the Carrera de Indias), the iconography of Our Lady of the Candelaria and all sorts of variations on it soon spread across the Americas aided by missionary activities.2 Our Lady of the Candelaria in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection is a fine illustration of this, as it was painted by an artist probably active in the Peruvian city of Cuzco. In the eighteenth century, the territory belonged to the Spanish Crown, and was known as the Virreinato del Perú or the Viceroyalty of Peru.3 The scene in the painting is a variation on the miracle statue of Tenerife, as the doves were omitted. The Christ Child blesses with his left hand and holds a globe in his right: he is the Salvator Mundi, or Saviour of the World.

In keeping with the miracle statue of Tenerife, Mary is holding a candle. The candle, as well as the doves, refer to the Presentation in the Temple described in the Gospel of St Luke, who is merging two different Jewish ceremonies in one.4 According to Jewish law, every first-born boy had to be dedicated to God after around forty days in the temple. During this ceremony, called Pidyon ha-ben, the father buys the child’s freedom by paying five shekels to the priest. Around the same time – forty days after the child’s birth – the new mother also had to purify herself by making a sacrifice. Usually this was a dove and a lamb, but if she could not afford that, two doves sufficed, as in Mary’s case. Often, the purification ceremony (Qorban yoledet) did not take place on the same day, but both ceremonies were commemorated together, being depicted with Joseph and Mary presenting the Child in the temple while carrying a basket with two doves as an offering. In Western Christianity, the Feast of the Presentation in the Temple became known as Candlemas. Pope Sergius I (687-701) introduced a procession featuring candles to mark the occasion, and two centuries later the custom developed in which candles were consecrated to celebrate Mass, hence the name.5

Yet Mary was not like all other mothers. After all, she was a virgin mother and, moreover, was not burdened with the sins of inheritance. This is precisely what Our Lady of the Candelaria in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection emphasises. The crescent moon at the Virgin’s feet is often associated with the Immaculata Conceptio or the Immaculate Conception. Although, according to Catholic teaching, only Christ can assume the role of mediator between man and God, Mary was often seen as intercessor. As a result, she was also associated with the moon as a bridge between heaven and earth. And as the moon reflects the light of the sun, so does Mary with the image of her Son, making her the role model of role models.6

Painted sculpture

Not only does the iconography of Our Lady of the Candelaria refer to the miracle statue of Tenerife, the way Mary and Jesus are depicted also refers to religious sculpture. The distinctive S-shape of the candlestick in Mary’s hand can be linked to the actual use of decorative statues on altars featuring candles. The candlesticks were shaped in such a way as to reduce the risk of fire; the flame could thus be kept further away from the wooden statue and her precious clothing.7

The triangular shape of Mary’s robe in Our Lady of the Candelaria is also reminiscent of the garments used to decorate actual sculptures. Statues that were intended to be dressed were called vestideras or de vestir. The bodies consisted of simple wooden structures; only the visible parts – the head, hands and feet – were executed in greater detail.8 They were often attributed miraculous properties and were therefore depicted in paintings, as it was thought that part of that miracle power would be transferred to the painting itself. Our Lady of the Candelaria belongs to these vera effigies: trompe-l’oeil representations of real religious statues, including the jewellery, curtains, flowerpots and candles with which they were adorned. These ‘painted sculptures’ were common, and were erected both in churches and in places of worship for private devotion.9

Two for the price of one

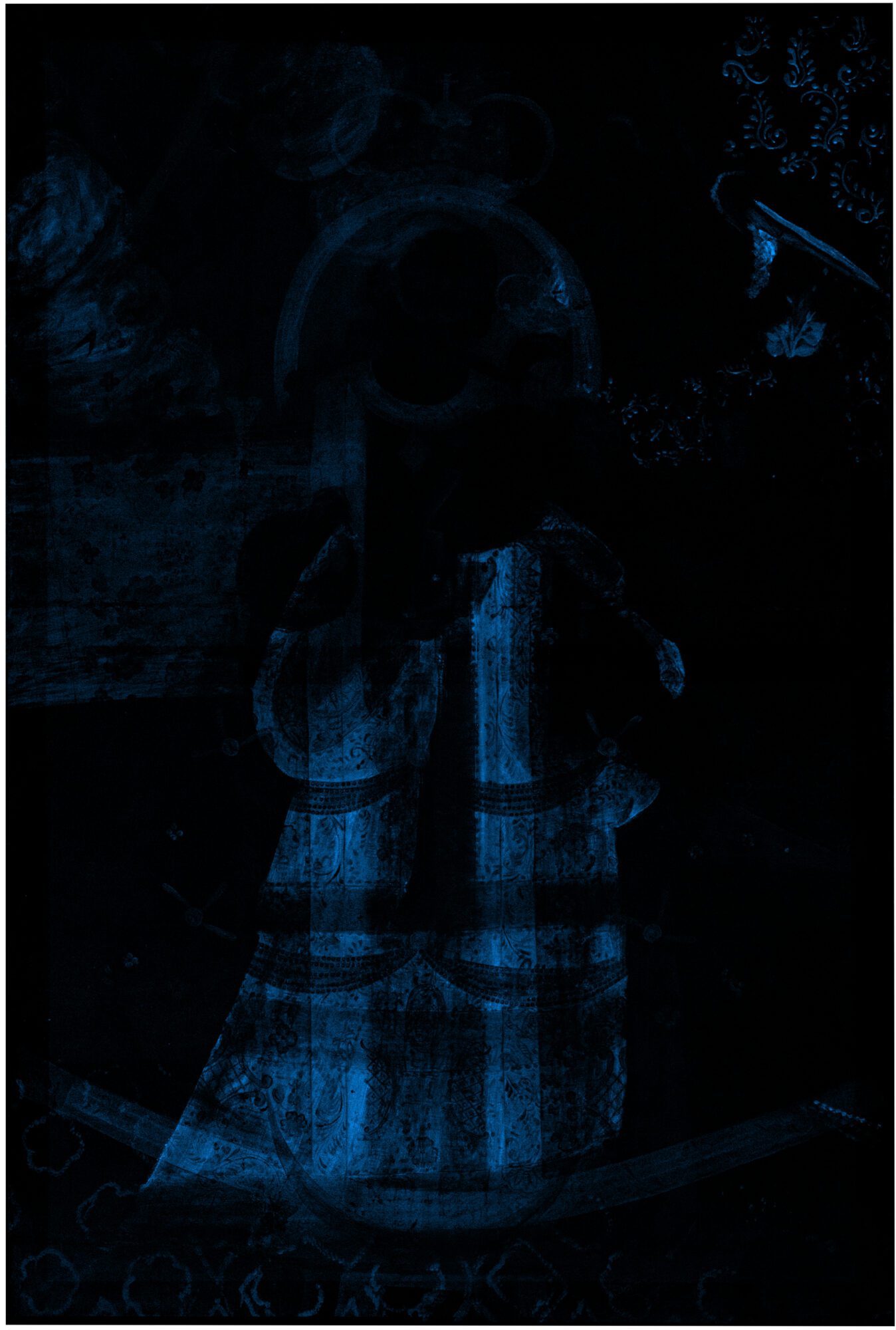

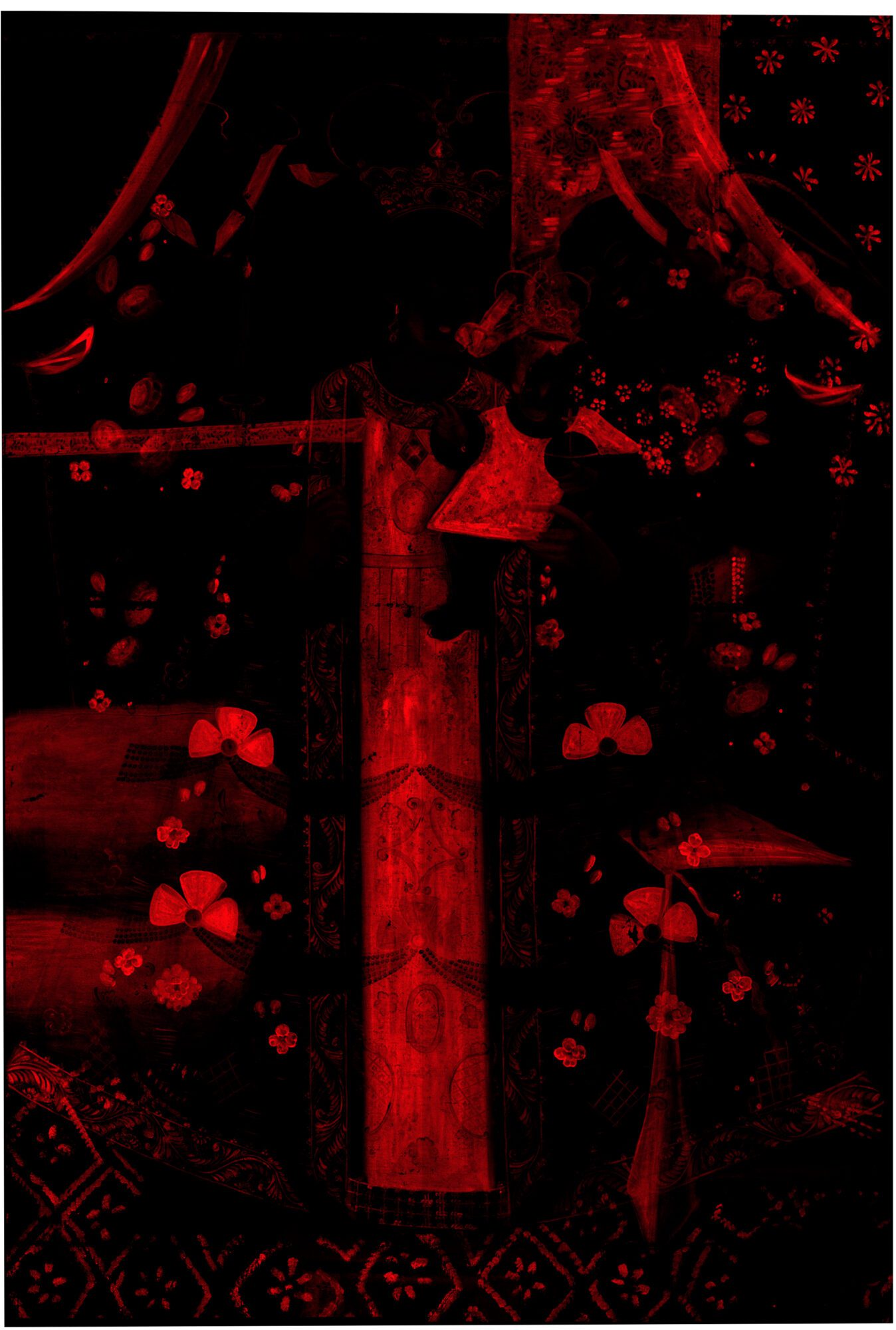

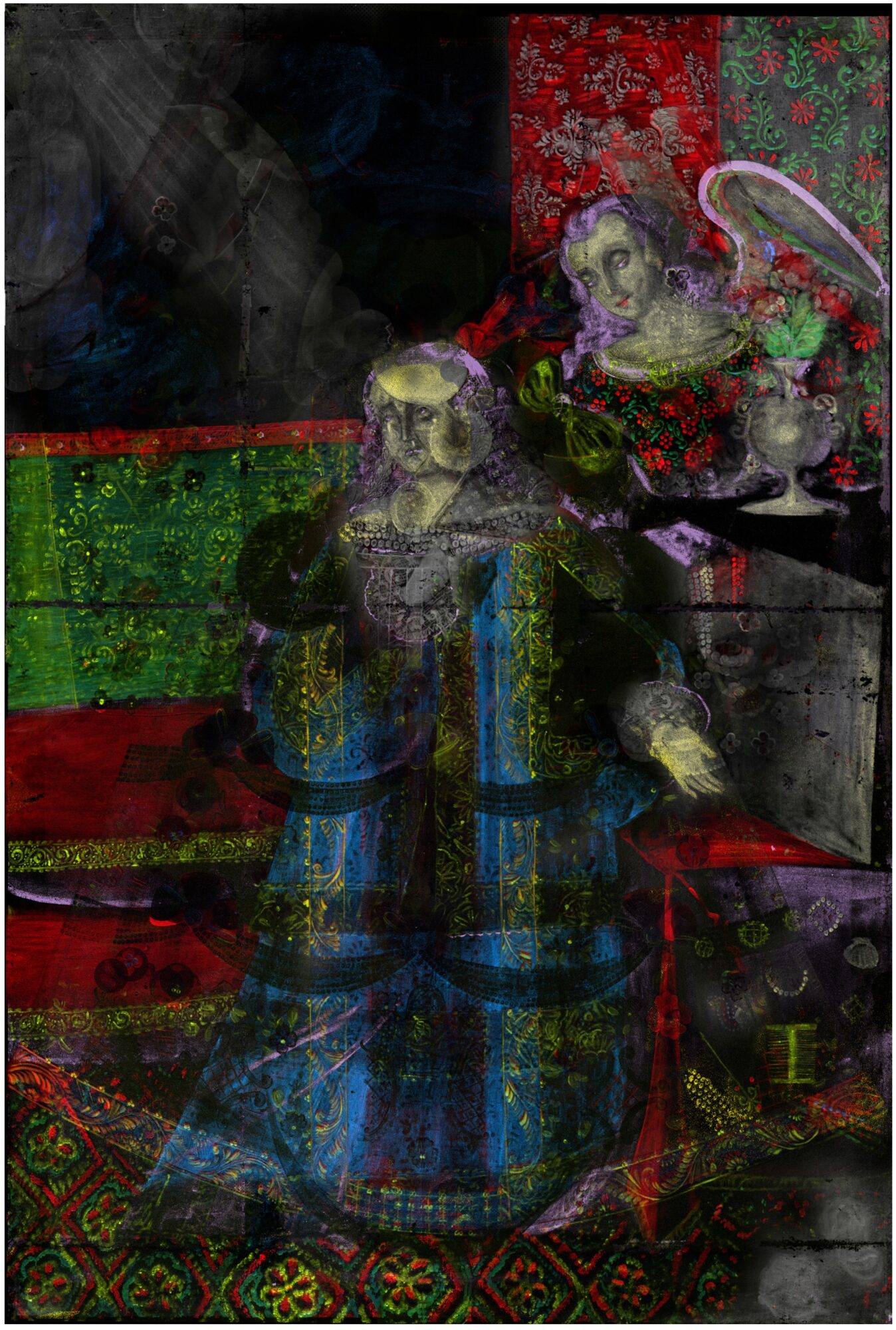

Our Lady of the Candelaria was analysed in detail using various imaging techniques: macro-X-ray fluorescence scanning (Ma-XRF), X-ray radiography (XRR), ultraviolet fluorescence (UVF), infrared reflectography (IRR) and infrared false colour photography (IRFC).10 Macro-XRF scanning in particular yielded unexpected results. This non-invasive imaging technique identifies a range of chemical elements present in different paint layers. These elements give us an idea of the pigments used. For example, the element mercury (Hg) indicates the bright red pigment vermilion. In addition, Ma-XRF scanning can reveal underlying paint layers or compositions.11 And what transpired? Hidden underneath Our Lady of the Candelaria is a detailed depiction of a penitent Mary Magdalene!

Vermilion, a red pigment obtained naturally by crushing cinnabar or chemically from mercury and sulphur, was used, for example, in the clothes, ribbons and curtains of Our Lady of the Candelaria, as well as in the wall decoration and tablecloth in the overpainted depiction of Mary Magdalene.12 Her dress was painted using smalt blue. This artificial pigment, obtained by pulverising glass coloured with cobalt oxide, can become opaque and discoloured over time when mixed with oil. Because it was cheaper than the other available alternatives, it was widely used in Europe in the eighteenth century, as well as in Lima and the Andean region.13

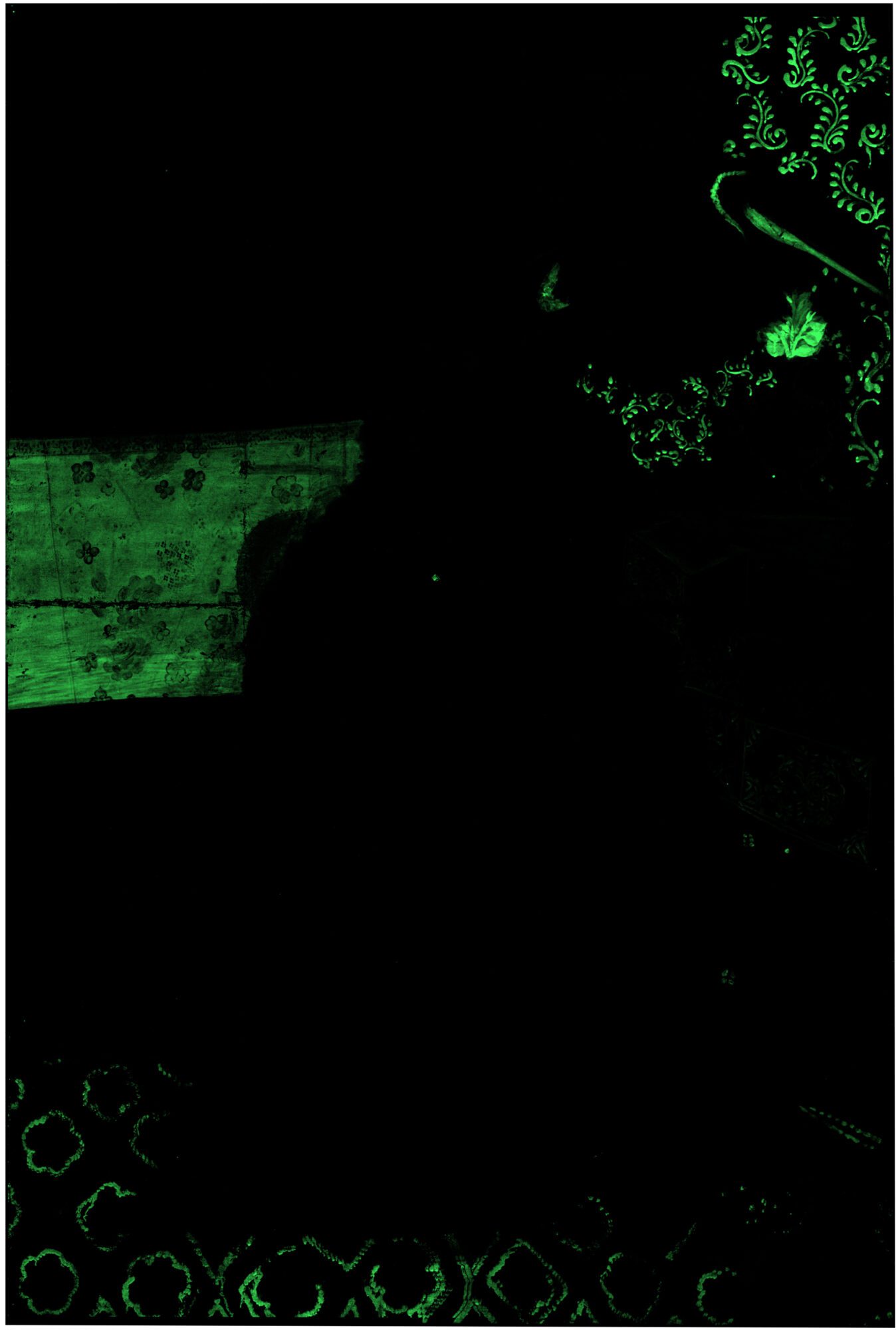

Lead-tin yellow, commonly used since the seventeenth century, and which can be related to glass production, was detected too.14 So was orpiment, also known as yellow arsenic, which often appears in pre-Hispanic murals and remained popular with painters of the ‘Cuzco school’. For the greens, a copper-based pigment was used, perhaps malachite, verdigris or some other mixture.15

Overpainted Mary Magdalene

The iconography of Mary Magdalene was booming in Europe after the Council of Trent in 1563. The latter’s aim was to reform the Catholic Church from within, re-profiling its teachings and rituals in the face of heretical Protestantism. Converted following a sinful existence, Mary Magdalene was the prime example of penance and reconciliation. By depicting her as a rich courtesan who renounced her wealth, she symbolised the rejection of worldly life and vanity.16 Besides, she was not just a saint: she was the first to see Christ after he had risen as she made her way to his tomb to embalm his body. This is why the ointment jar is her main attribute.

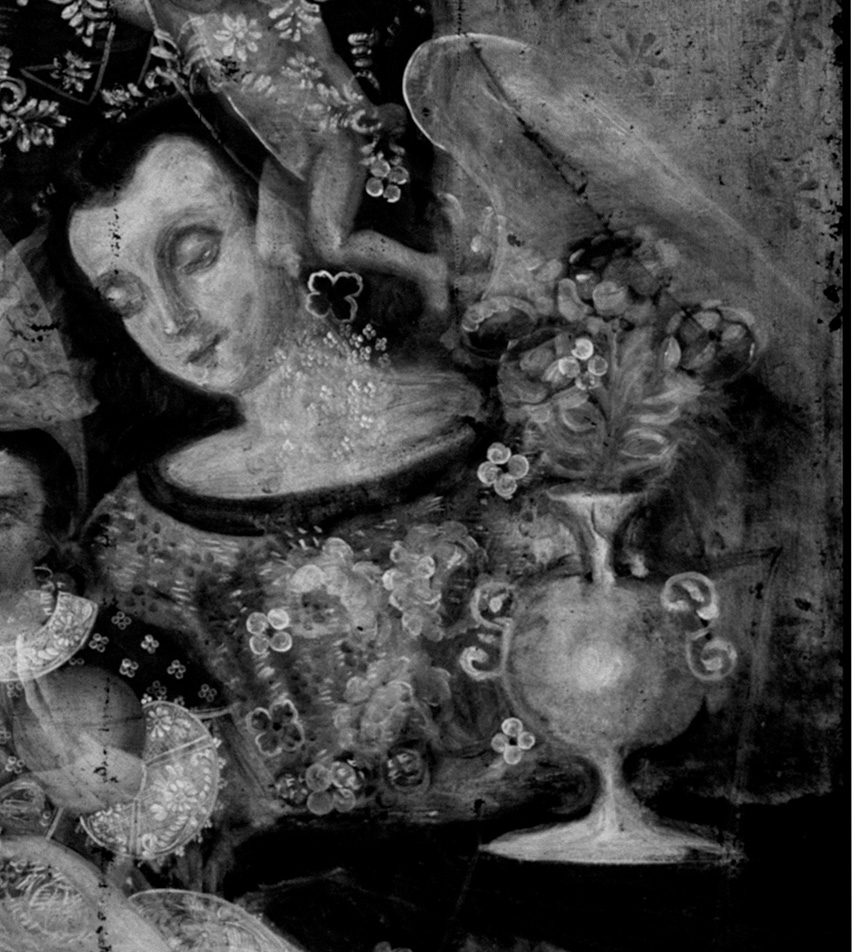

Several representations of the penitent Mary Magdalene also circulated in Peru, and all are derived from the same model. Probably a widespread but as yet unidentified engraving served as the ultimate source of inspiration for these figures. The same applies to the concealed Mary Magdalene in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection. Compared to other examples, such as in the Barbosa-Stern collection in Lima, the execution of The Phoebus Foundation’s version is more refined and richly elaborated with all kinds of details.17 Mary Magdalene is displayed in an area of the room called the estrado, a distinguished women’s space in the homes of the Spanish elite. It consisted of a raised platform furnished with rugs, cushions, small furniture, and textile wall hangings. Such rooms were also introduced in interiors in Spanish America.18

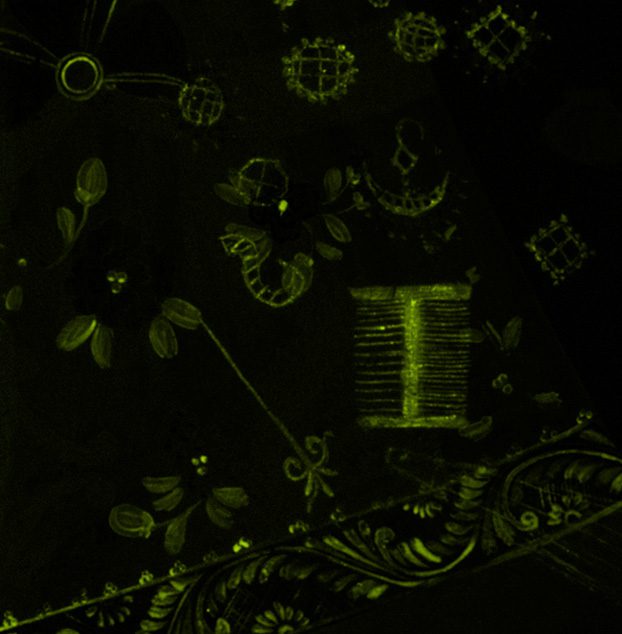

Furthermore, the painter aimed to showcase Mary Magdalene’s earthly prosperity through her elaborate toilette. Thanks to the macro-XRF scan, various accessories and jewellery can be seen: a comb, pearl necklaces, brooches, hair jewellery, a pin, a shell, a mirror, a small bottle of perfume and probably a fan. The pin possibly refers to the tupu and ttipqui pins, which Inca women used to fasten their dresses and which were still in circulation during the period of the Viceroyalty.19 In turn, the perfume bottle, or pomo, is a symbol of luxury because of its expensive contents, but is also a nod to Mary Magdalene’s ointment jar.20

Noteworthy too is that, as far as we know, only The Phoebus Foundation’s version features an angel in Mary Magdalene’s room, dressed in a lavish tunic featuring floral designs, a large bow and a brooch on the chest. Such jewellery was fashionable in Spain in the second half of the seventeenth century, especially during the reign of Charles II (1665-1700).21 This date is also consistent with Mary Magdalene’s attire: a dress with a straight neckline trimmed with pearls and openwork puffed sleeves with detailed lace, a fashion trend that can be dated back to around 1670.22

Efficient production

The ‘Cuzco school of painting’ flourished in the first half of the eighteenth century because of the considerable demand for paintings in the Viceroyalty of Peru.23 When demand is high, supply has to keep up. So there was large-scale production, preferably carried out as efficiently as possible. This meant that artists had to be clever about the division of labour in their studios, with assistants in charge of some parts of the composition while the master focuses on the most important areas of it, which translated into differences in the execution and quality of the finished paintings.24 Besides the mass-produced pieces, which were mainly intended for the market, the ‘Cuzco school’ also produced higher-quality work commissioned by more affluent clients. The highly refined execution of Our Lady of the Candelaria in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection suggests that it was painted to order.

However, the import, production and distribution of textiles – and thus also of painter’s canvas – in Peru proved to be a complex issue.25 As linen or hemp were not produced there, these fabrics had to be imported from Europe, making them difficult to obtain and therefore more expensive. In addition, Peru’s geographical location with its high plains and remote ports, hampered cloth imports. The high demand for paintings, and subsequent semi-industrial production meant that reusing canvas was not that unusual, in order to reduce costs and speed up production. Perhaps the studio where Our Lady of the Candelaria was produced was also working as cost-efficiently as possible or was struggling with a temporary shortage of canvas, and the Mary Magdalene was therefore – sadly – painted over. Another possibility would be that the commissioner of the Our Lady of the Candelaria provided the artist with the painting of Mary Magdalene, for the canvas to be reused, a practice that was not unusual.26 However, fortunately, recent conservation treatment made it possible to catch a glimpse of this overpainted scene, and the virgin Mary briefly became a penitent Mary Magdalene once more.

How to cite this item?

González Juste, ‘From Mary Magdalene to the Virgin Mary. A Glimpse Underneath the Paint Layers of an Eighteenth-Century Our Lady of the Candelaria’, Phoebus Findings, https://phoebusfoundation.org/phoebus_findings/7/, accessed on [dd.mm.yyyy].

All rights reserved. No part of this Phoebus Finding may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from The Phoebus Foundation. If you have comments or want to make use of our images, we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: info@phoebusfoundation.org

Footnotes

- J. de Orellana Rojas, ‘Variaciones sobre el tema de la Virgen de la Candelaria. La advocación mariana en el sur andino peruano y la evolución de su iconografía’, Revista de Arquitectura, 2 (2015): 91-128.[↩]

- Local people were very active patrons and maintained chapels and celebrations for local saints. J. Porres, ‘La difusión de modelos en la pintura devocional del barroco en el virreinato del Perú’, in: N. Campos Vera (ed.), Mestizajes en diálogo. VIII Encuentro Internacional sobre Barroco: historia, arquitectura, arte, antropología, literatura, gastronomía, La Paz, 2017: 23-33; P.F. Amador Marrero & C. Rodríguez Morales, ‘Aportaciones a la iconografía de la Candelaria isleña en América’, in: C. Rodríguez Morales & A.D. Laguna (eds.), Imagen y reliquia. Nuevos estudios sobre la antigua escultura de la Candelaria, s.l., 2018: 129-257.[↩]

- It was vast, as it included not only Peru but also the whole area between present-day Panama and Argentina, excluding Brazil.[↩]

- D.C. Shorr, ‘The Iconographic Development of the Presentation in the Temple’, The Art Bulletin, 28 (1946): 17-32; S. Ward, ‘The Presentation of Jesus: Jewish Perspectives on Luke 2:22-24’, Shofar, 21 (2003): 21-39.[↩]

- On this pope, see ‘Saint Sergius I, pope’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Sergius-I, accessed 01.12.2022. See also Shorr 1946: 17-32. De Orellana Rojas 2015: 91-128 refers to the Jewish tradition of blessing the candles.[↩]

- J. Peinado Guzmán, ‘Simbología de las letanías lauretanas y su casuística en el arzobispado de Granada’, in: J. Peinado Guzmán & M. Rodríguez Miranda, Lecciones barrocas: ‘aunando miradas’, Córdoba, 2015: 159-190.[↩]

- E. Telias Gutiérrez, ‘Breves señalamientos a dos imágenes marianas’, in: I. Cruz de Amenábar, E. Telias Gutiérrez, A. Fuentes González et al., Vírgenes Sur Andinas. María, territorio y protección, Santiago de Chile, 2014: 14-17.[↩]

- R. Sigüenza Martin, ‘Arte y devoción popular: una imagen vestidera en el Museo Cerralbo’, Museo Cerralbo, Pieza del mes, enero (2010): 1-25.[↩]

- Porres 2017: 23-33.[↩]

- Imaging performed by Adri Verburg, Ma-XRF scanning by David Lainé (IPARC), for which we extend our thanks.[↩]

- For more information on Ma-XRF scanning and other analysis techniques, see: S. Van Dorst, Crazy about Dymphna. The Story of a Girl who Drove a Medieval City Mad, Veurne, 2020: among others 39, 43, 97-104, 110-113, 182-183, 220-241.[↩]

- The mines of Huancavelica in Peru were the main source of vermilion in South America. The pigment had ritual significance for the native people, who called it ichma or llimpi, and it was used for art and body decoration. R. Bruquetas Galán, ‘Técnicas y materiales en la pintura limeña de la primera mitad del siglo XVII: Angelino Medoro y su entorno’, Revista de arte Goya (2009): 144-161. Vermilion fluoresces with an ochre-yellow tone on IRFC images. M. Herrero-Cortell, P. Artoni, J. Madrid et al., ‘Caracterización de pigmentos históricos a través de técnicas de imagen, en diversas bandas del espectro electromagnético’, Ge-conservación, 22, 1 (2022): 58-75.[↩]

- Ibidem. R. Bruquetas Galán, Técnicas y materiales de la pintura española en los siglos de oro, Madrid, 2002: 149-150.[↩]

- During the eighteenth century, this pigment was replaced by ‘Naples yellow’ and yellow lead oxide, ‘massicot’. Bruquetas Galán 2009: 144-161.[↩]

- This pigment, like lead white, was imported from Spain and often cropped up in trade registers. Bruquetas Galán 2009: 144-161.[↩]

- E. Monzón Pertejo, ‘Cubrir el cuerpo y transformar el alma: la conversión y la penitencia de María Magdalena en la pintura barroca y el cine’, in: R. García Mahiques & S. Domenech García, Valor discursivo del cuerpo en el barroco hispánico, Valencia, 2015: 265-276; L. Wijna, The Lamentation of the Dying Mary Magdalene. Melchior de la Mars (c. 1580-1650) and the power of emotion in the Counter-Reformation, Phoebus Focus, 20, Veurne, 2021.[↩]

- For a picture of this work, see the Colección Barbosa-Stern website: https://barbosa-stern.org/siglo-xviii/, accessed 21.03.2024.[↩]

- P.L. Betancourt, ‘La sala doméstica en Santa Fe de Bogotá, siglo XIX. El decorado: la sala barroca’, Historia critica, 20 (2000): 93-106.[↩]

- D. Pierce & J. Wilson Frick, Glitterati. Portraits & Jewelry from Colonial Latin America, Denver, 2015.[↩]

- E. Monzón Pertejo, ‘La evolución de la imagen conceptual de María Magdalena’, in: R. Zafra Molina & J. Azanza López, Emblemática trascendente: hermenéutica de la imagen, iconología del texto, Pamplona, 2011: 529-540; A. Gutiérrez Usillos, ‘Obsesión por los sabores y olores. Un universo mágico para los sentidos’, and ‘El recuerdo de América en España. El ajuar de Doña María Luisa y de otras damas nobles a finales del siglo XVII’, in: A. Gutiérrez Usillos, La hija del Virrey. El mundo femenino novohispano en el siglo XVII, Madrid, 2019: 85-220, 455-487.[↩]

- Gutiérrez Usillos 2019: 455-487.[↩]

- This clothing style, developed in Lima at the end of the seventeenth century and consolidated during the eighteenth century, was a feminine adaptation of a military doublet. D. Terreros Roldán, Historia de la indumentaria virreinal limeña: en búsqueda del origen de un traje tradicional para Lima, Lima, 2021: 76. See also A. Gutiérrez Usillos, ‘Estudio comparativo del retrato de Doña Maria Luisa’, in: A. Gutiérrez Usillos, La hija del Virrey. El mundo femenino novohispano en el siglo XVII, Madrid, 2019: 221-260.[↩]

- See also K. Van Cauteren, The Holy Family in Nazareth. On Diego Quispe Tito (c.1611-1681), the art of Cuzco, and Antwerp as Hollywood on the Scheldt, Phoebus Focus, 35, Veurne, 2023.[↩]

- In large Spanish and Flemish studios, it was quite common to specify tasks. Apprentices and assistants worked alongside the masters, each focusing on executing just one part of the painting, such as hands, faces, the landscapes or floral motifs. A. Balta Campbell, ‘El sincretismo en la pintura de la Escuela Cuzqueña’, Cultura, 23 (2009): 103-113; L. Wuffarden, ‘The rise and Triumph of the Regional Schools, 1670-1750’, in: L. Alcala & J. Brown, Painting in Latin America 1550-1820: from Conquest to Independence, New Haven, 2014: 307-364.[↩]

- Bruquetas Galán 2009: 144-161.[↩]

- Ibidem.[↩]