New Information About the Baroque Composer Henricus Liberti

Dr. Leen Kelchtermans

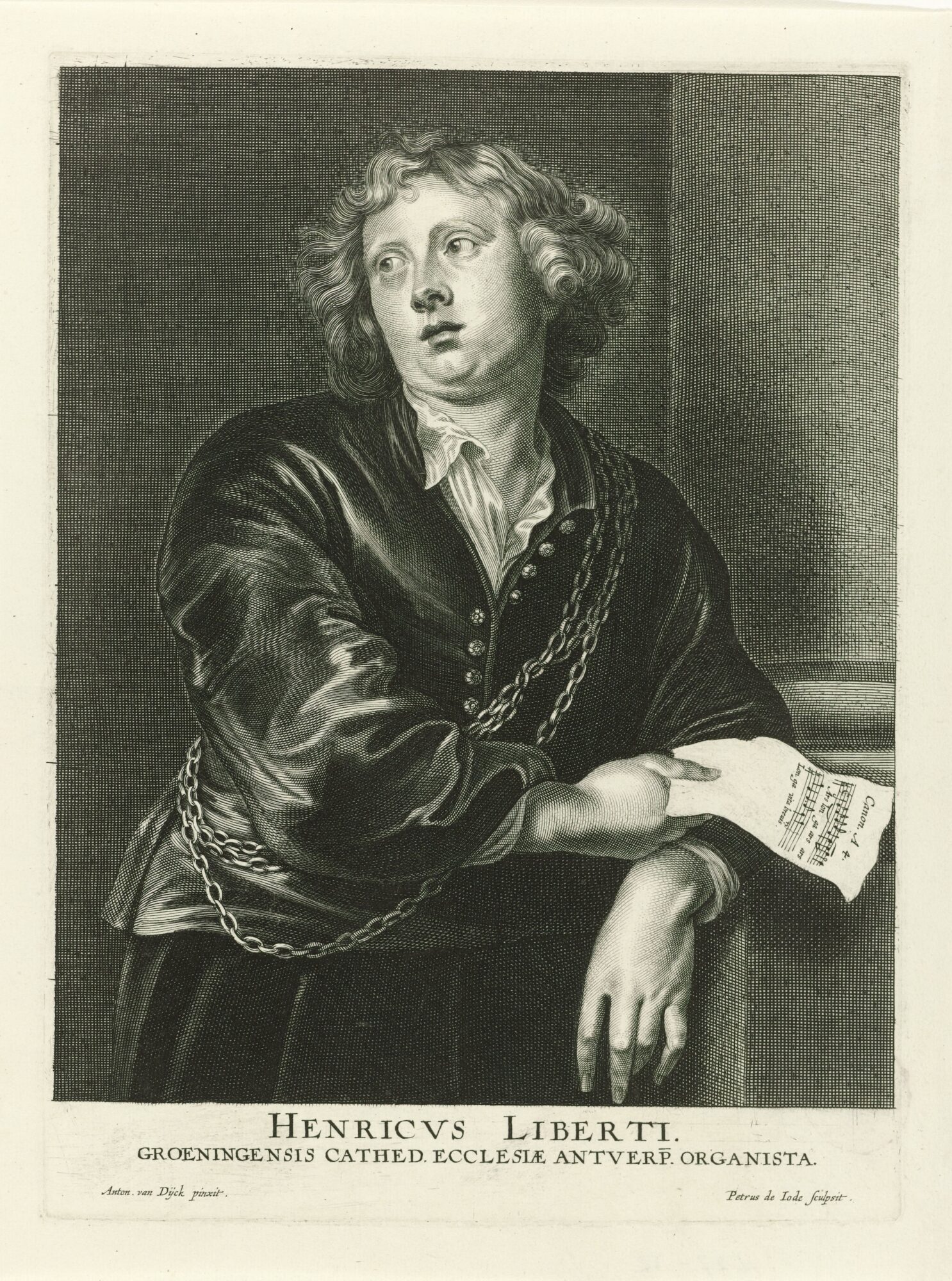

Anthony Van Dyck, Portrait of Henricus Liberti, c.1627-1632. Oil on canvas, 114 x 88.5 cm. Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation

Baroque portrait virtuoso Anthony Van Dyck painted the compelling portrait of Henricus Liberti (c.1610-1669) between 1627 and 1632.1 The blond-haired young man is gazing into the distance, lips slightly parted. He adopts a nonchalant posture, his shirt collar unbuttoned. Van Dyck masterfully captured his inspired, melancholic gaze and the light reflecting on his black outfit. The portrait was not only distributed in different versions and copies, but also in print form. The inscription under the engraving by Pieter De Jode II confirms the identity of the person in the portrait: ‘Henricus Liberti. Groeningensis Cathed. Ecclesiæ Antverp. Organista’ (‘Henricus Liberti of Groningen, organist of Antwerp’s Church of Our Lady’).

In the painting a musical score can be seen on the white piece of paper Liberti holds in his hand. In the print a legible text has been added. In both cases, the score probably refers to one of Liberti’s own compositions. The text ‘Ars longa, vita brevis’ proclaims that an artist’s life is fleeting like everyone else’s, but his art lives on. In retrospect, that adage turns out to apply to the composer himself to some extent. Although much of his music, such as a collection of instrumental dance music, was lost or only partially preserved, complete compositions also survived. It includes a pair of organ pieces, two motets and two cantiones natalitiae. The latter are polyphonic Christmas carols, accompanied by Latin or Dutch lyrics, that recount the Biblical story of the nativity, the birth of Christ. They were very popular in Antwerp during the first half of the seventeenth century, and unique to the city on the Scheldt. At Christmas, they were performed during or after the liturgical service in the cathedral by the church choir, accompanied by Liberti on the organ. Today, Liberti is best known for the cantiones natalitiae. While his oeuvre partly withstood the test of time, there is not much we know for certain about the organist’s life.

Biographical puzzle

We do not know where or when Henricus Liberti was born.2 It was probably in around 1610. His surname Liberti with the suffix ‘Groeningensis’ indicates that his father’s name was Libertus or Librecht (Liberti is ‘of Librecht’) and that he was from Groningen. The eighteenth-century biographers Arkstee and Merkus mention that the Librecht family was well-to-do, although no specific records are known to confirm this.3 Yet, the family must have been rich enough to allow Henricus to take music lessons so that he could develop his talent. Arkstee and Merkus also indicate that Liberti resided in several northern Netherlandish cities before settling in Antwerp. In fact, ‘Henri’ Liberti was, according to them, ‘le plus habile organiste qu’il y eut alors à Anvers’. The city on the Scheldt was an important centre for music in the seventeenth century, which was also home to the famous Ruckers family who produced coveted harpsichords.4 Liberti may have been a young choirboy in Antwerp’s Church of Our Lady as early as 1617. One thing we can be certain of is that in 1626 he was allowed to replace the church’s ailing principal organist, John Bull. When the latter died in 1628, Liberti was appointed his successor. Liberti served as the permanent organist at the Church of Our Lady until his own death in 1669.

Besides these snippets of information about Liberti’s professional life, his personal life is also sparsely documented. On 8 January 1631, he married Lucretia Gardini, daughter of the wealthy merchant and broker Herman Gardini and Marie de Francqueville.5 Whether or not it was true love is a mystery; on the other hand, it was definitely a smart move. Liberti was an immigrant and through his marriage he firmly entrenched himself in the city on the Scheldt’s wealthy middle class. It was also precisely in these circles that musical culture flourished. House concerts were organised and learning to play a musical instrument was considered an important part of your offspring’s education.6 In August 1632, the Liberti couple had a son, Johannes Antonius.7 Meanwhile, Liberti’s fame as an organ player and expert was also on the rise. In 1633, he was even offered a position in Archduchess Infanta Isabella’s music chapel in Brussels. However, the organist declined the offer. The reason for this is still unknown. A second son, Ludovicus, was born in September 1634.8 Between 1632 and 1651, a number of Liberti’s compositions appeared in music compilations. Several of these were published in Antwerp by the heirs of Peter Phalesius, who owned the most important music printing firm in the Low Countries.

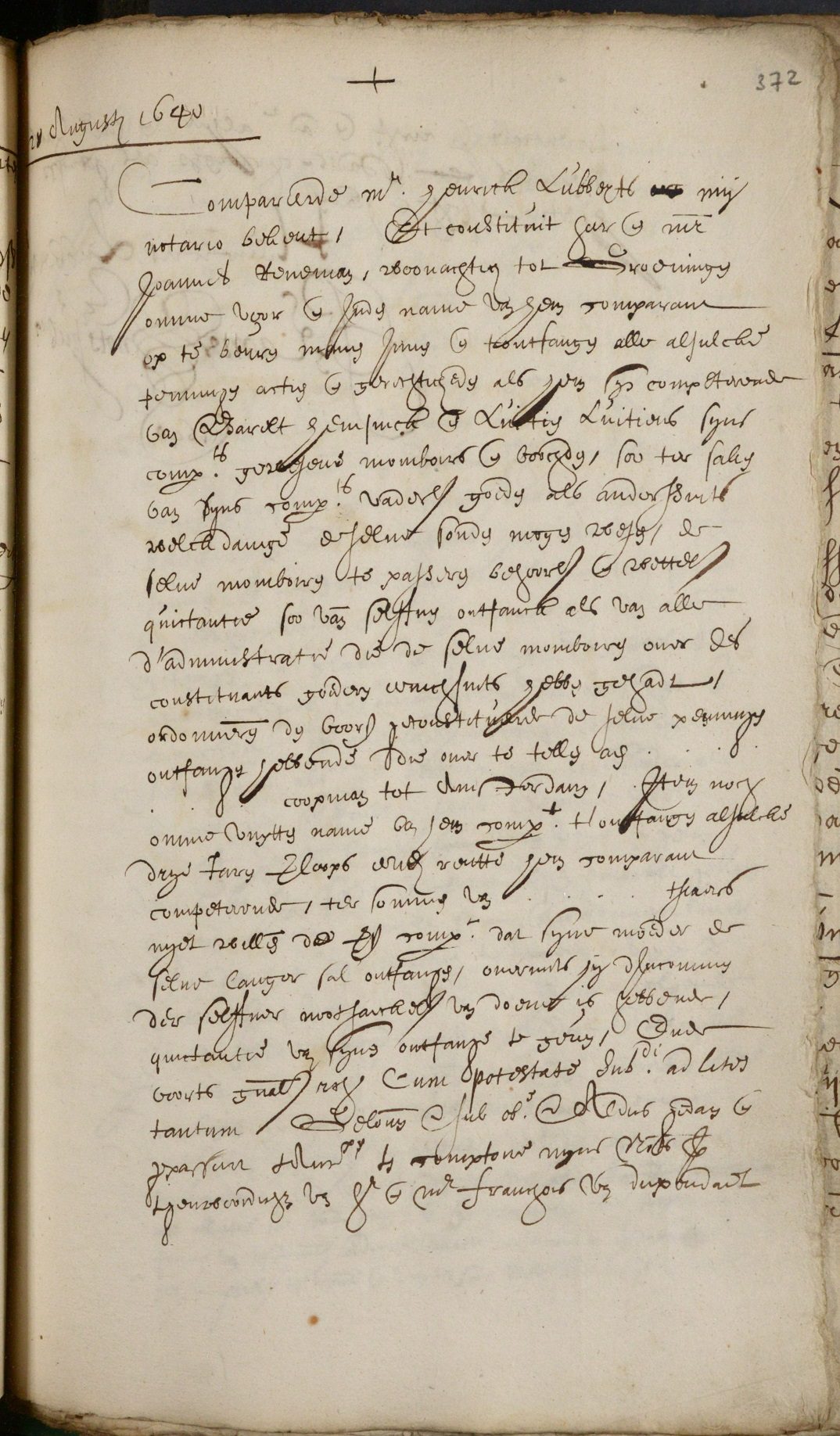

Three recently discovered archive documents – two notarial deeds and a bundle of court documents –provide new pieces of information that allow us to add substance to the few details we know about Liberti’s life outlined above. They can all be dated between August 1640 and January 1642, during the heyday of his career.

Link with Groningen

On 28 August 1640, ‘Henrick Lubberts’ – in the seventeenth century the spelling of first names and surnames was by no means fixed – visited Antwerp notary Pieter Lams.9 He instructed a certain Joannes Reneman, ‘living in Groningen’ (‘woonachtich tot Groeningen’) to collect on his behalf all ‘sums of money, legal claims and everything to which he is entitled’ (‘penningen actien ende gerechticheden’) relating to his father’s property from his former guardians Barelt Hemsinck and Luitien Luitiens. For the first time, Liberti’s family link with Groningen is actually confirmed in an archive document. The fact that the musician had guardians indicates that he lost his father before he came of age. So perhaps it was not so much the religious turmoil, as Prims assumed, that explains Liberti’s stay in several northern Netherlandish cities before he settled in Antwerp. With no father to support them, the young Liberti’s family basically had to fend for itself. In that respect, his musical talent and ditto upbringing probably helped him survive. Liberti expected Reneman to report to him and gather any available paperwork concerning his father’s property. The money he was to receive was to be transferred to a merchant in Amsterdam. Unfortunately, the latter’s name is not mentioned. It is unclear why the organist specified the transaction to be conducted this way. Did Liberti still owe the merchant money or would the Amsterdammer take the money to Antwerp? All in all, it is certain that Liberti’s network of contacts extended not only to the city on the Scheldt, Brussels and Groningen, but thus also to Amsterdam.

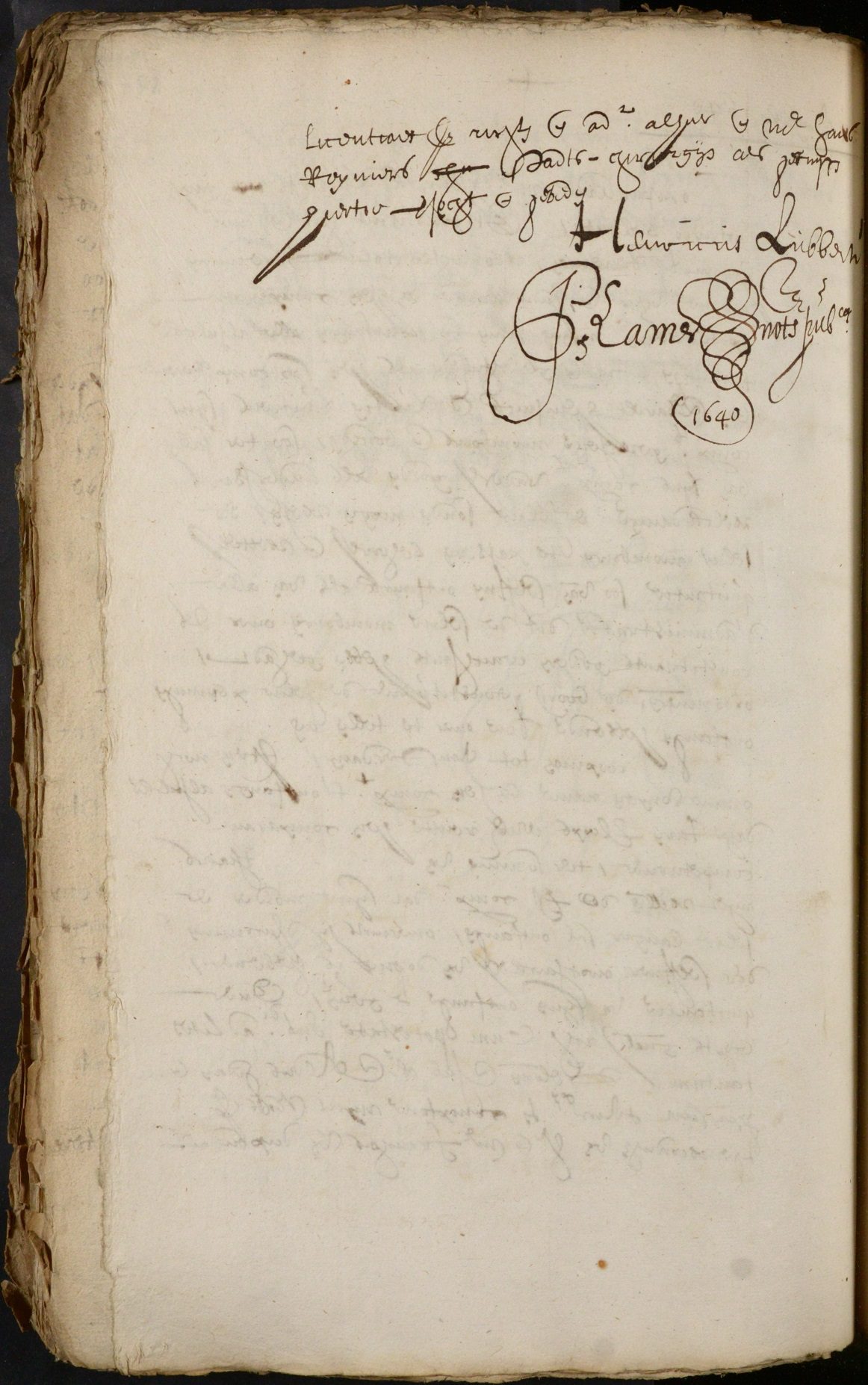

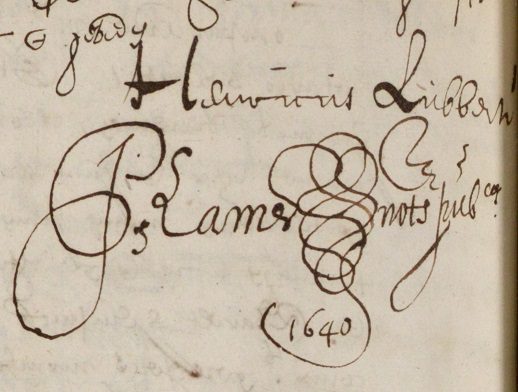

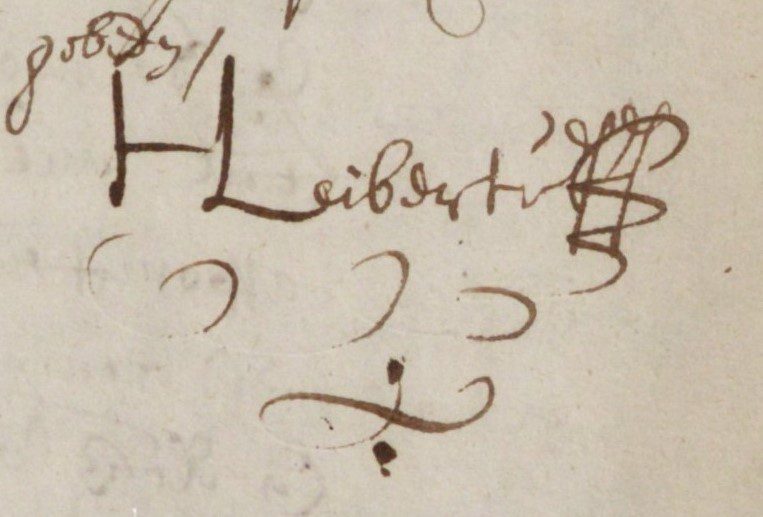

Apparently, Reneman had been working for Liberti for some time. For three years, he had been receiving the proceeds of interest in the organist’s name. The corresponding sum per year was not specified. Either way, Reneman had always paid the money to Liberti’s mother. But now that was to end. He did not want ‘his mother to receive the money any longer, because he needs that income himself’ (‘sijne moeder de selve langer sal ontfangen, overmits hij dIncommen der selffver nootsaeckelijk van doene is hebbende’). Since Reneman lived in Groningen and he transferred the money to Liberti’s mother, it seems logical that she also resided in Groningen. Perhaps she was still a widow in need of financial support? Or was it less of a hassle to give the money to her? And why did Liberti change his mind? It is difficult to ascertain whether the organist was in dire need of money. It does not seem very likely since he had been married to the daughter of a wealthy merchant for almost a decade by 1640. The fact that the amount was not specified makes it difficult to assess its importance. The witnesses present at the drafting of the deed – ‘Mr Franchois van Diependael, who has a degree in law and is a lawyer in Antwerp and Mr Hans Reyniers city surgeon’ (‘Sr ende Mr. Franchois van Diependael licentiaet in de rechten ende advocaat alhier ende Mr. Hans Reyniers Stadts-chirurgijn’) – may well indicate the circles in which Liberti moved: in the growing group of well-educated and affluent Antwerp residents. Although notary Lams called him ‘Henrick Lubberts’ in the deed, the organist signed his name in full as ‘Henricus Libberti’. It is the first signature known of the composer. But not the only one, as he also signed the second discovered notarial deed.

Standing surety

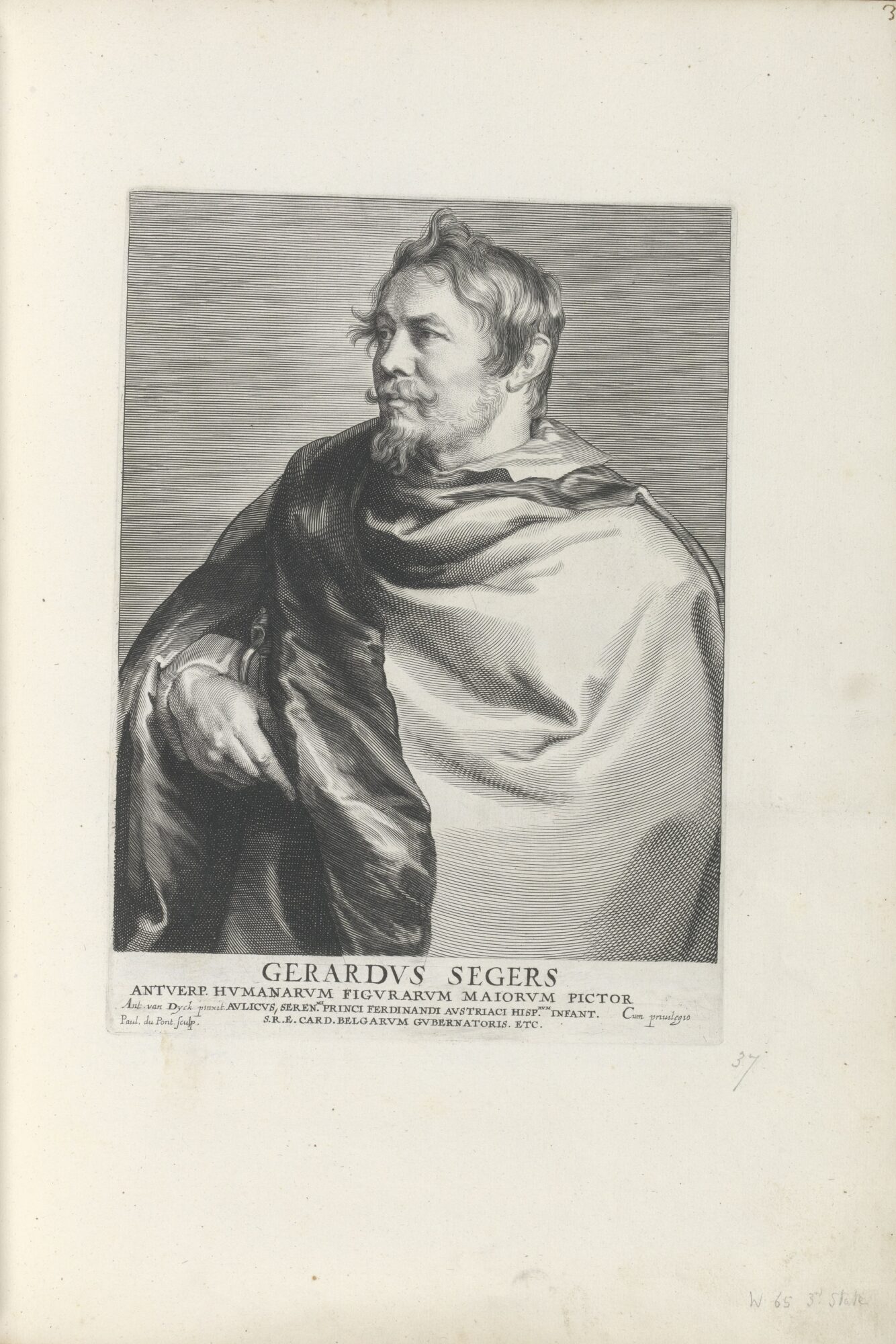

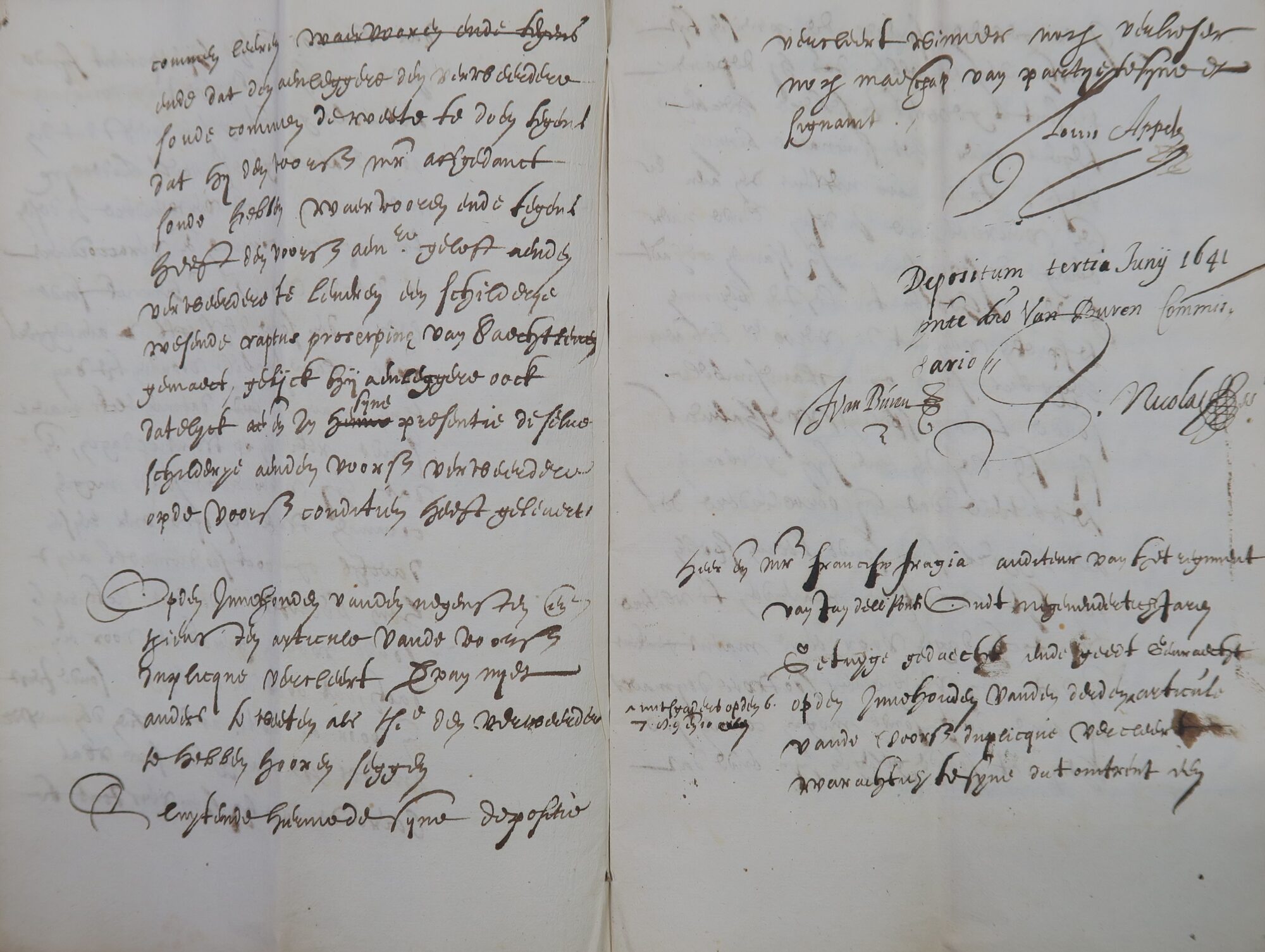

On 4 December 1641, ‘Mr Henrick Liberti, organist and resident of Antwerp’ (‘Mr. Henrick Liberti, organist ingesetene deser Stadt’) visited notary Lams again.10 He also signed this document in ornate letters: ‘HLiberti’. The musician wanted to reinforce his promise to stand surety for the litigation costs of ‘Sr. Geraert Segers’. The latter was involved in a conflict with a certain ‘Mr. Jan de Jonge’. Their case appeared before the Council of Brabant, but at the time the deed was drafted, a verdict had not yet been delivered. So it was still unclear who had to pay the legal costs – Segers or De Jonge. Whether ‘Sr. Geraert Segers’ refers to the Caravaggist painter Gerard Seghers (1591-1651), is not certain but not unlikely either. In December 1641, the master was residing in the city on the Scheldt, as in both May 1641 and June 1642 he was registered as a member of the Sodality of the Married Men of Age (Sodaliteit der getrouwden).11 Seghers’ portrait print, like Liberti’s, was included in Van Dyck’s Iconography (1645-1646). Did the composer and the painter know each other? His opponent ‘Jan de Jonge’ cannot be identified with certainty either; his name is not very unique, which does not help.

The fact that Liberti stood surety for Segers implies not only a bond of trust between the two gentlemen but also that the organist was wealthy enough to make such a commitment and, as the record shows, to renew it. Not much is known about Liberti’s financial situation other than his marriage to a wealthy merchant’s daughter. His annual salary as organist of Antwerp’s Church of Our Lady was one hundred guilders.12 For a similar amount – one hundred twenty and one hundred fifty guilders to be precise – you could order, respectively, a harpsichord, an instrument Liberti also played, or a three-quarter portrait, such as that of the musician, by Van Dyck.13 Given his reputation, it seems very plausible that he also earned additional income by playing the organ for specific chapels in the Church of Our Lady, composing occasional music, performing at house concerts and giving music lessons.14

Liberti, the music teacher (conspicuous by his absence)

The fact that Liberti also gave lessons can be substantiated for the first time thanks to the third archive document discovered. It concerns a bundle of court documents related to the lawsuit Pauwels Lodewycx brought against Liberti in October 1640.15 At the beginning of that year, the two gentlemen had met in the inn located ‘opposite the Seminary of the Most Venerable Bishop’ (‘tegens over het Seminarie van den Eerweerdichsten Heere den Bisschop’). It was run by Guilliamme Van Swol, and was frequented by both Lodewycx and Liberti. After negotiations lasting about two hours, they struck a deal. Lodewycx would give Liberti two paintings for him to come and teach Gomarus (aka Gommer), his seventeen-year-old son, ‘to play the harpsichord’ (‘comen leeren opde claversingel’). As early as 1583, Antwerp’s Burgomaster for external affairs and security (buitenburgemeester), Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, advised noble boys to embrace the art of music: it was one of ‘the arts suitable for an honest young man’ (‘de kunsten die gepast zijn voor een eerlijke jongeman’).16 And what is good for the nobility, the bourgeoisie is keen to emulate. Liberti would teach him a ballet for ‘a small painting of a tobacco drinker/smoker, not worth more than ten pennies’ (‘een schilderyken wesende eenen toebackdrincker nyet weert synde thien stuyvers eens’). It probably concerned a genre painting of a pipe smoker of an inferior quality. The reason why people in the seventeenth century described smoking as ‘drinking tobacco’ can possibly be explained by the same narcotic effect produced by smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol, or by the similar way in which the smoke was inhaled by sucking and the alcohol was drunk by slurping.17

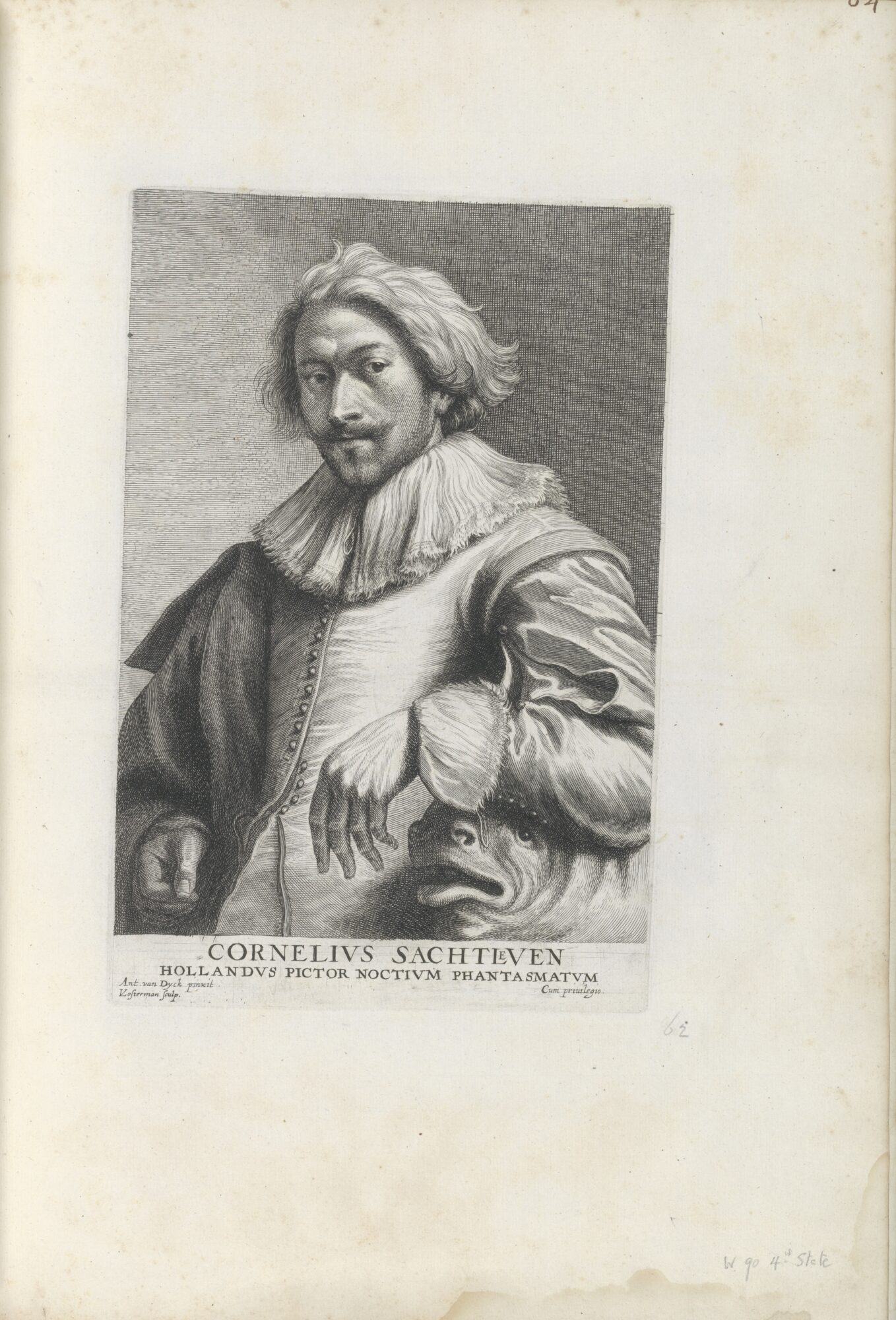

The second painting was of a different calibre. It was ‘painted by a certain experienced master Saechtleven. It depicted the Abduction of Proserpina. It was skillfully done with strange figures such as evil spirits, magicians and the like. Moreover, it was a nocturnal scene with burning candles or torches. Had the plaintiff [Pauwels Lodewycx] sold this painting to other art lovers he would have done them a great service’ (‘geschildert door sekeren geexperimenteerden meester Saechtleven behelsende in figure Raptum Proserpina, dat was constich gemaeckt van vrempde figuren als van boose geesten, tooveraers ende dyer gelycke, ende oock in forme van eenen nacht als behelsende brandende flambeeuwen oft fackelen met welck stuck den voorschreven Aenlegghere [Pauwels Lodewycx] int vercoopen noch eenich besunder profyt aen andere Liefhebbers van de conste soude hebben gedaen’). This depiction of the Abduction of Proserpina, the Greek goddess of the underworld and springtime, was apparently imbued with all the elements highly regarded by art theory of the time: it was a history painting, a night scene, playing with the effect of light and featuring all kinds of fantasy figures. The painter was most probably Cornelis Saftleven (1607-1681) from Rotterdam, who resided in Antwerp in the early 1630s. He even collaborated with Peter Paul Rubens, which we can deduce from the four ‘Sachtleuen’ paintings in the inventory of Rubens’ art collection, which explicitly states that the latter had painted the figures.18 Van Dyck also painted Saftleven’s portrait during this period, which was later included in print form in his Iconography. Liberti was given the painting to teach Gomarus Lodewycx for ten months. It actually amounted to a total of two hundred lessons, as it was specified that a month would consist of twenty ‘days’ (‘dagen’) and that Liberti ‘would be allowed to visit two, three or four times a day, or even as often as he wanted, and each time he visited would count for one day’ (‘soude mogen commen twee, dry ofte vier reysen daechs oft oock soo dicmaels alst hem belieffde ende dat elcke reyse soude worden gerekent voor een dach’). This suggests that Lodewycx had his own harpsichord at home, on which Liberti would teach his son to play. Liberti took delivery of the two paintings and set one condition: he would not start the series of lessons until Lodewycx dismissed (‘affdancken’) his son’s current harpsichord teacher. The aggrieved teacher, who incidentally was still willing to testify in support of Lodewycx, was Ferdinand Godrick, a young man aged twenty-eight ‘who came to teach the children to play the harpsichord’ (‘gaende de kinderen leeren opde claversingel’). He was cast aside for ‘Master Hendrick’ (‘Meester Hendrick’) who, ‘as far as the art of playing and teaching the harpsichord’ (‘de conste van te spelen ende te leeren spelen opde clavercimbale’) is concerned was ‘outstanding’ (‘seer is excellerende’). The deal was struck and they drank ‘a jug of wine’ (‘eenen pot wyns’) on it, at Lodewycx’s expense.

And then the quarrel began, because the lessons never materialised. According to Liberti, Lodewycx did not inform him about whether or not Godrick had been dismissed from his teaching assignment, and in the meantime kept himself ‘available’ (‘gereedt’) to begin his. In the end, he was not able to because Lodewycx ‘is said to have secretly sent his son to Leuven to study for two years there from St Bavo’s Day [i.e. on 1 October] onwards’ (‘synen sone stillekens naer Leuven gesonden, seggende dat hy van Bamisse aff aldaer twee jaeren lanck moeste blijven studeren’). He considered the idea that he would now have to return the two paintings ‘absurd, ridiculous and contrary to all right and reason’ (‘absurd, ridiculeux ende strydende teghens alle recht ende redene’). After all, the agreement had been broken by Lodewycx and ‘against the will’ (‘teghens den wille ende danck’) of the composer. Lodewycx took a very different stance. Liberti never showed up, even though, as his wife Elisabeth Smekens also testified, he had already ‘relieved Godrick of his duties and paid him’ (‘affgedanckt ende betaelt’). After having been confronted about this several times, Liberti is said to have promised ‘out of embarrassment’ (‘vuyt beschaemptheyt’) ‘to refund the cost of the two paintings’ (‘den prijs vande selve schilderijen te betaelen’). Lodewycx agreed and gave him the name of the ‘old clothes dealer’ (oudkleerkoper) from whom he had bought the pieces so the musician could inquire how much they had cost.19 But again, he heard nothing from Liberti, forcing him to take legal action against him. He demanded the return or payment of the two paintings. Moreover, he vehemently denied – as did his wife, for that matter – that he had sent his son to Leuven. Gomarus attended school every day at the Augustinian Fathers in Antwerp, where he was in the sixth grade. He would only start studying at Leuven University on 1 October 1641. ‘They are pure fantasy and far-fetched excuses made up by Liberti’ (‘Al soo dat naeckte fabulen ende opgesochte vuytvluchten syn die [Liberti] is voortbrengende’)! And the fact that the composer continued to ignore him, provoke him and even delay court proceedings by providing documents too late (which meant Liberti had to pay ‘late submission costs’ (‘costen van retardatien’) did not make Lodewycx any less ‘miserable’ (‘verdrietich’).

The court case dragged on and on. The last document mentioned is dated 13 January 1642, almost two years after the agreement was concluded. Among others, city clerk Jan Gaspar Gevaerts – aka Gevartius – collected the court documents to present them to the mayor and aldermen of the city on the Scheldt. It is notable that Gevaerts’ portrait print after Van Dyck’s sketch was also included in the Iconography, as were those of the other protagonists in this Phoebus Finding – Liberti in the starring role, as well as Saftleven and probably Seghers too. How the case ultimately concluded remains a mystery.

What is certain is that the bundle of court documents teaches us a great deal. Not only do the documents provide information about Liberti’s secondary income as a music teacher (and perhaps also about his character?). They also highlight how private music teaching assignments were discussed, how such lessons were conducted and that paintings were used as a means of payment for them. Together with the two discovered notarial deeds, the bundle of court documents offers a new perspective on the life of the ‘outstanding’ (‘excellerende’) Baroque organist Henricus Liberti. At the same time, like little pebbles, they form part of the winding paths of both music and art history and the intersections at which the two converge. Ars – and artium historia – longa, vita brevis.

How to cite this item?

L. Kelchtermans, ‘New Information About the Baroque Composer Henricus Liberti’, Phoebus Findings, https://phoebusfoundation.org/phoebus_findings/4/, accessed on [dd.mm.yyyy].

All rights reserved. No part of this Phoebus Finding may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from The Phoebus Foundation. If you have comments or want to make use of our images, we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: info@phoebusfoundation.org

Footnotes

- For recent publications about this portrait, see L. Kelchtermans, ‘From Ambition to Self-Mockery. Baroque Artists’ Portraits in the Collection of The Phoebus Foundation’, in: K. Van Cauteren, The Bold and the Beautiful in Flemish Portraits, Veurne, 2020: 347-355; T. De Paepe, Portrait of Henricus Liberti. A Musical Painting by Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641), Phoebus Focus, 27, Veurne, 2022.[↩]

- See F. Prims, ‘Oud-Antwerpsche portrettengalerie: Hendrik Liberti van Groeninge (1600-1669)’, Zondagsvriend (15.07.1937), which can be consulted via Antwerp, City Archives Felixarchief (AFA), HN#586; R. Rasch, ‘Henricus Liberti, organist van de Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-Kerk te Antwerpen (1628-1669)’, in: A. Dunning (ed.), Visitatio Organorum. Feestbundel voor Maarten Albert Vente aangeboden ter gelegenheid van zijn 65e verjaardag, vol. 2, Buren, 1980: 507-518; R.A. Rasch, ‘Liberti, Henricus’, Grove Music Online (2001), doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.16571; De Paepe 2022.[↩]

- J.C. Arkstee & H. Merkus, Iconographie ou Vies des hommes illustres du XVII. siècle, vol. 1, Amsterdam/Leipzig, 1759: 133.[↩]

- T. De Paepe et al., Antwerpen klavecimbelstad: twee eeuwen uitzonderlijke muziekinstrumenten uit Museum Vleeshuis/Klank van de Stad, Antwerp, 2018.[↩]

- AFA, Parochieregisters, Marriage Records Church of Our Lady South, PR#197, fol. 46r.[↩]

- T. De Paepe, ‘Klavecimbels, virginalen en orgels in Antwerpen’, in: Klavier. Virginalen, klavecimbels en orgels verbeeld in de 16de en de 17de eeuw, Kontich, 2022a: 74-75.[↩]

- AFA, Parochieregisters, Baptism Records Church of Our Lady South, PR#14, fol. 100r.[↩]

- AFA, Parochieregisters, Baptism Records Church of Our Lady South, PR#14, fol. 130v.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Pieter Lams, N#2367, fol. 372r-372v.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Pieter Lams, N#2367, fol. 465r.[↩]

- P.F. Rombouts & T. Van Lerius, De Liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche Sint-Lucasgilde, onder zinspreuk ‘Wt ionsten versaemt’, vol. 1, Antwerp, [1864-1876]: 424 note 1; A. Delvingt, ‘A Self-Portrait by Gerard Seghers, “Tres Expert Peinctre En Grand”’, The Burlington Magazine, 147 (2005): 112-114.[↩]

- In 1650, it was increased to one hundred fourteen guilders. Rasch 1980: 513; De Paepe 2022: 47.[↩]

- B. Timmermans, Patronen van patronage in het zeventiende-eeuwse Antwerpen. Een elite als actor binnen een kunstwereld, Amsterdam, 2008: 159; De Paepe 2022: 47.[↩]

- De Paepe 2022: 47.[↩]

- AFA, Processen, 7#9129.[↩]

- De Paepe 2022a: 74.[↩]

- On this subject, see De Geïntegreerde Taalbank, under ‘tabak’, https://gtb.ivdnt.org/iWDB/search?actie=article&wdb=WNT&id=M067553.re.276&lemmodern=tabak~drinken, accessed on 26.11.2022; D. Geirnaert, ‘Tabak drinken’, Instituut voor de Nederlandse taal (11.10.2017), https://www.ivdnt.be/actueel/woorden-van-de-week/terug-in-de-taal/tabak-drinken/, accessed on 26.11.2022.[↩]

- F. Healy, ‘47. Een boer die zijn hond te eten geeft’, in: K. Lohse Belkin & F. Healy, Een huis vol kunst. Rubens als verzamelaar, exh. cat., Antwerp, Rubenshuis, 2004: 213. Saftleven’s scene of a vision, albeit only painted in 1660, gives some idea of how Lodewycx’s painting might have looked. See https://open.smk.dk/en/artwork/image/KMSsp435?q=saftleven%20cornelis&page=1, accessed on 26.11.2022.[↩]

- Oudkleerkopers usually, but not exclusively, traded in second-hand goods. J. Dambruyne, Corporatieve middengroepen. Aspiraties, relaties en transformaties in de 16de-eeuwse Gentse ambachtswereld, Ghent, 2002: 48.[↩]