Extraordinary Deathbed Portrait by Dirck van Delen

Dr Leen Kelchtermans

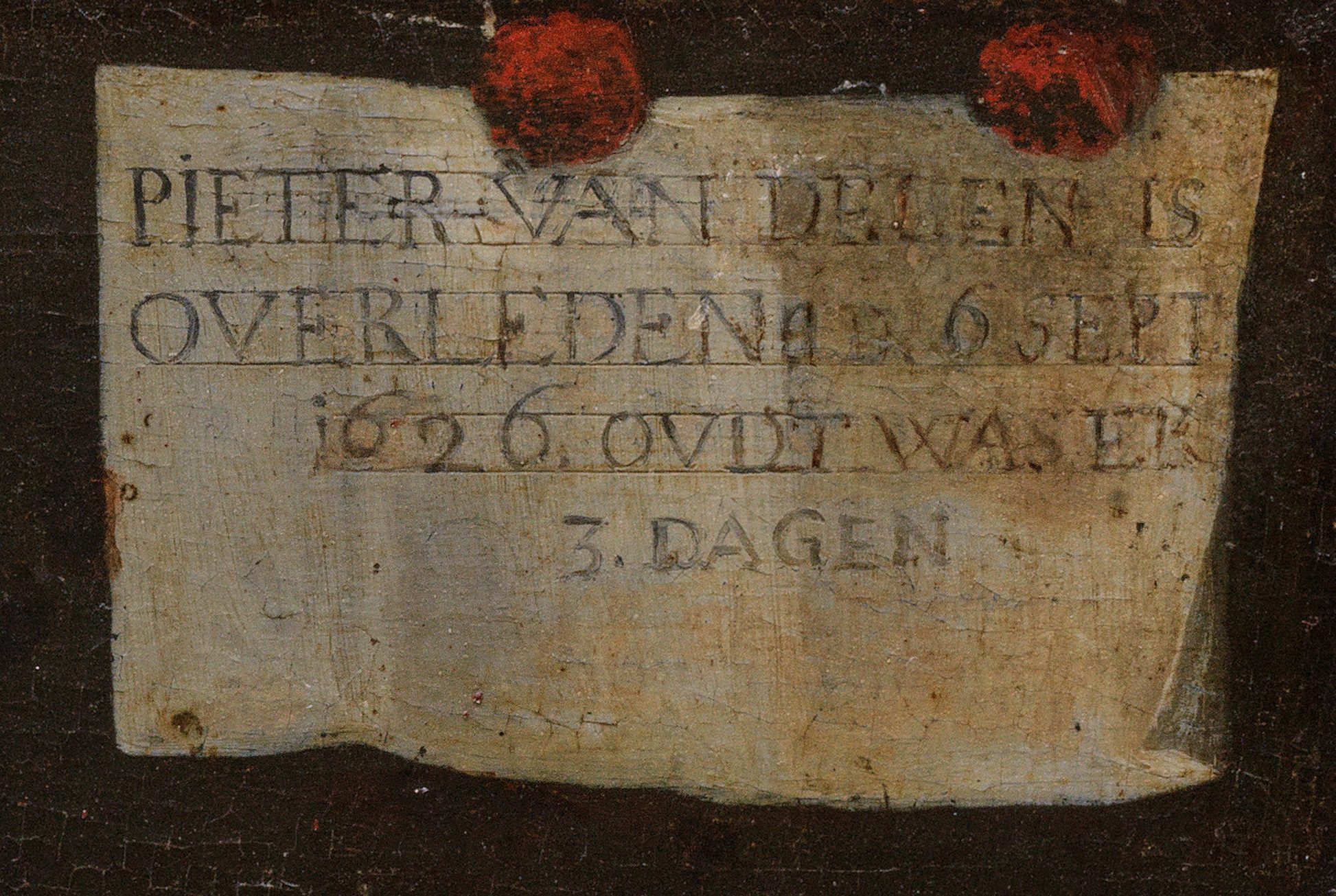

A child dressed in white with a wreath of twigs around his head lies, eyes closed, on rolled up fabric on a red surface.1 A black blanket completes his cot and contrasts sharply with the white sheet folded neatly over it. The background, too, is dark. The pale face and serenity exuded by the painting indicate that this is a deathbed portrait. This is also confirmed by the inscription on a trompe-l’oeil piece of paper in the top right-hand corner. It appears to be attached to the panel with two blobs of red wax. The inscription identifies the child as: ‘PIETER VAN DELEN IS OVERLEDEN A.D. 6 SEPT 1626. OVDT WAS ER 3. DAGEN’ (‘Pieter van Delen died on 6 September 1626, he was 3 days old’). The portrait has no other inscriptions. Initially, it was attributed to an anonymous master from the ‘Leiden school’.2 Who was Pieter van Delen and who painted his deathbed portrait?

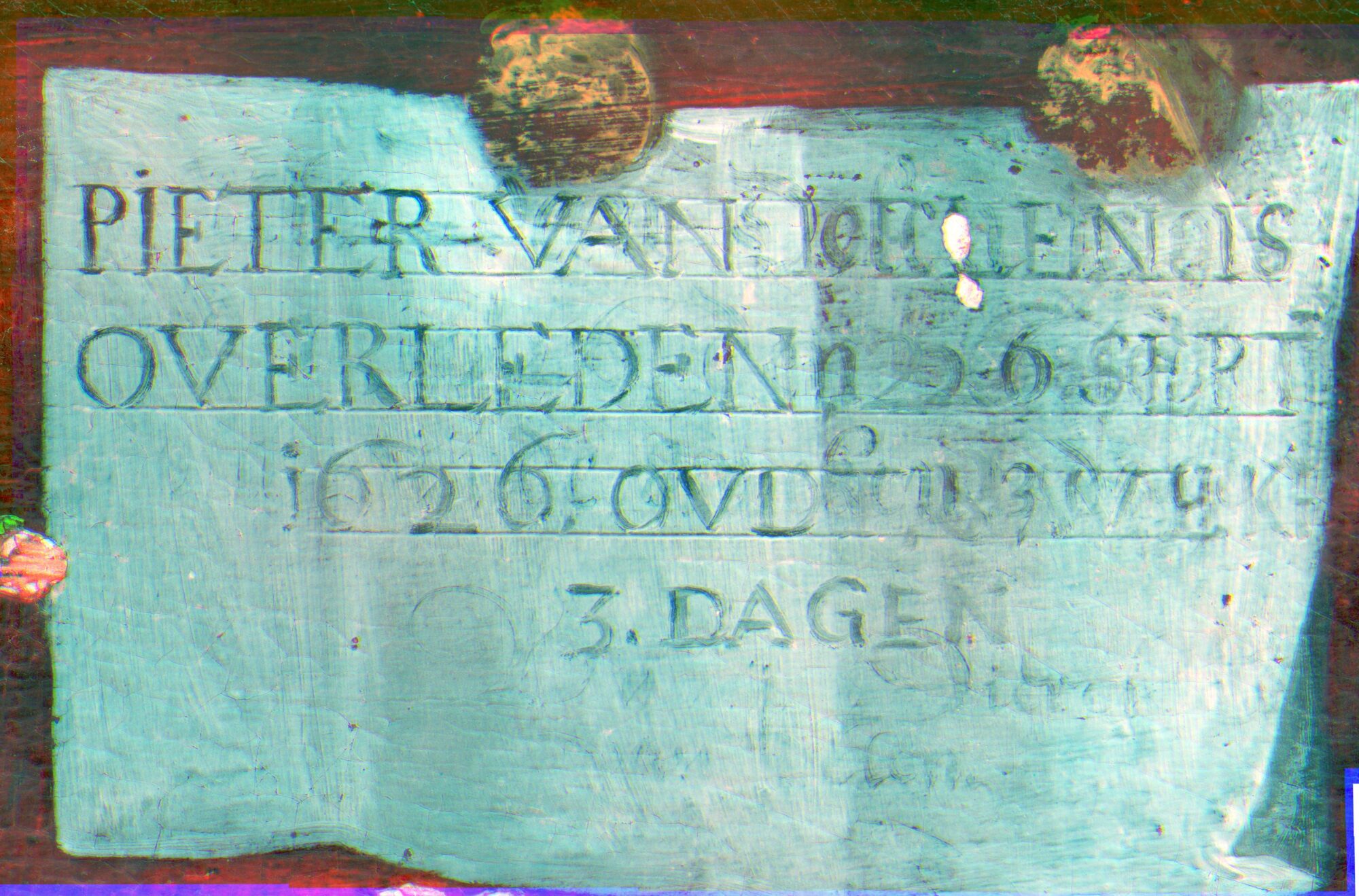

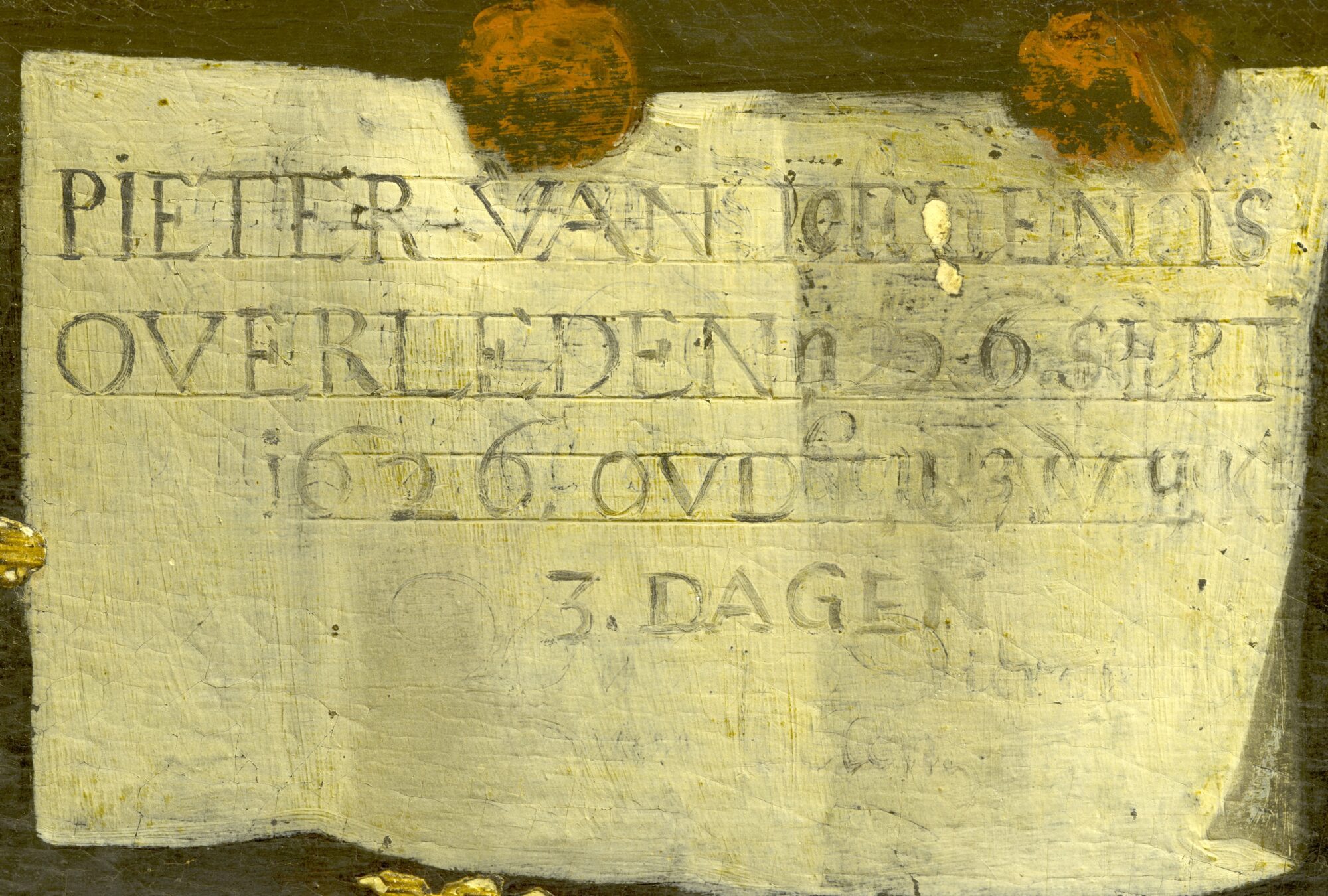

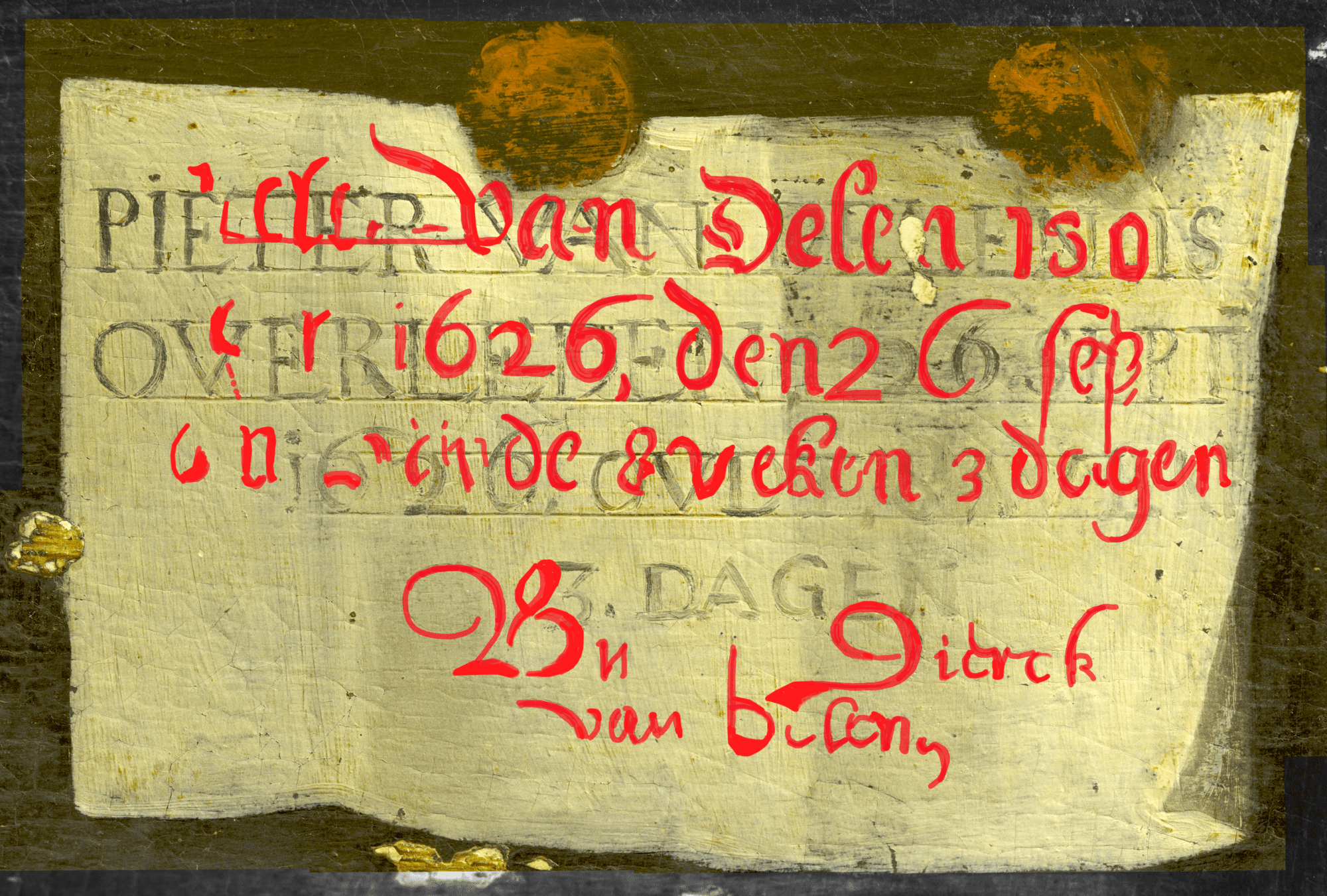

Overpainted inscription

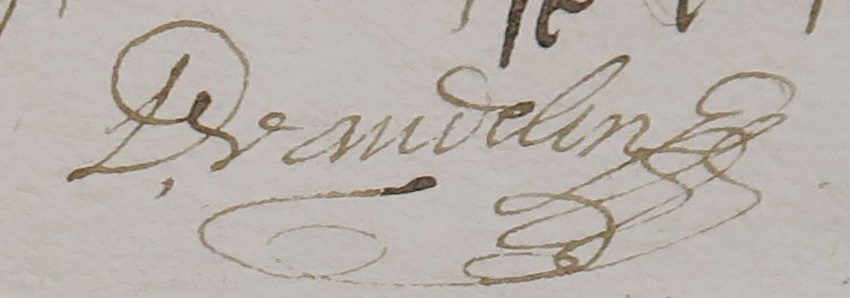

A thorough visual analysis of the panel reveals that ‘3 DAGEN’ (‘3 days’) is written differently from the rest of the inscription, whose letters appear with distinct outlines and are set between two lines. There also seem to be more words shining through the top layers of paint. Various image analysis techniques were used to try and make them visible again.3 Although an infrared image (IR) and false colour infrared image (IRFC) of the trompe-l’oeil piece of paper confirm that it originally featured a different text, they do not allow us to reconstruct the original inscription.4 After the varnish layer and overpaint were removed, it was possible to visualise the underlying text more clearly using infrared photography (IR) and infrared reflectography (IRR), during which images were taken at different wavelengths of the infrared spectrum (520-2200nm).5 This enabled the reconstruction of the original inscription on the deathbed portrait: ‘[P]iete[r] van Delen is o[verleden] 1626, den 26 sep o[u]d [z]ijnde 8 weken 3 dagen. By Dierck van Delen’ (‘Pieter van Delen died on 26 September 1626 at the age of 8 weeks and 3 days. By Dierck van Delen’).

Dirck, father of Pieter van Delen

This astonishing result sheds a whole new light on the deathbed portrait. First of all, it originally bore a signature: it was painted by Zeeland artist Dirck van Delen (Dirck Christiaensz. van Delen, 1605-1671).6 He was born in Heusden near ‘s Hertogenbosch, but moved to the Zeeland fishing village of Arnemuiden in 1625. Between 1639 and 1665, he registered in the Guild of St Luke in nearby Middelburg, although he continued to live in Arnemuiden.

On 23 August 1625, Van Delen announced his plans to marry Maria van der Gracht, who was almost 20 years older than him. She was the daughter of the then mayor. Their wedding took place on 21 September, and seven days later the painter also registered as a member of Arnemuiden’s Reformed Church.7 He became an official resident (poorter) there in 1628, and held the mayor’s office for several terms. After Maria van der Gracht died in 1650, Dirck van Delen married twice more. In 1651, he wed 33-year-old Catharina de Hane who died a year later, possibly in childbirth, and in 1658, he married the widow Johanna van Baelen, who was almost 60 years old.8

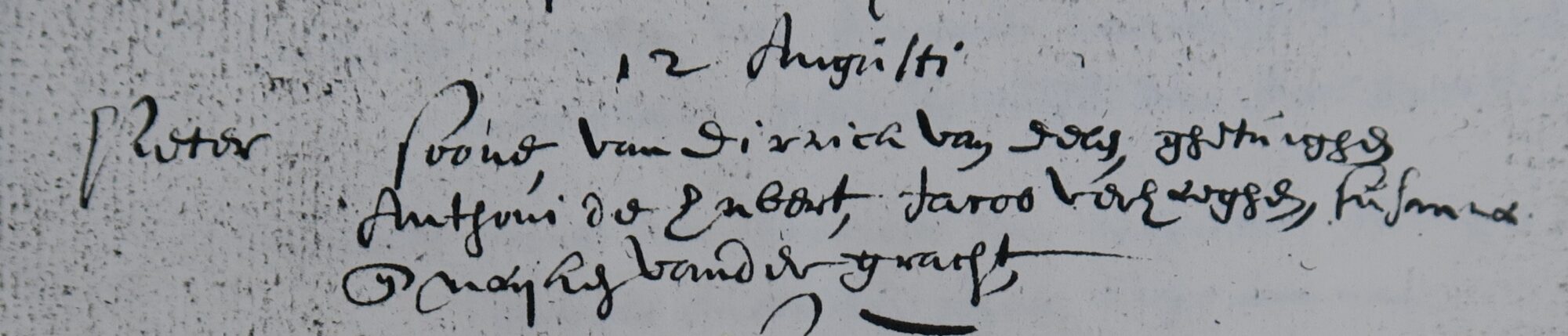

Thanks to the baptism records that have been preserved, it is known that Dirck van Delen and Maria van der Gracht did have a son named Pieter in 1626. He was baptised on 12 August.9 Moreover, he is the only child with that name born in Arnemuiden that year. The date of his death cannot be found in the parish registers because, unfortunately, the seventeenth-century burial records did not survive. Nevertheless, it seems very likely that Pieter died before 1671, as he is not mentioned as an heir in the resolutions of the village council in which, in September of that year, much was written about the debts of the deceased Dirck van Delen and the irregularities involving his estate that allegedly occurred to avoid confiscation.10 This makes it most probable that the son of Dirck van Delen, baptised in August 1626, is the Pieter the painter portrayed on his deathbed that same year. The reconstruction of the original inscription is also perfectly consistent with this theory. If Pieter was 8 weeks and 3 days old when he died, he was born in late July and baptised two weeks later. The reason why the date of his death, age and even his father’s signature were painted over, and by whom, remains a mystery (for now). Perhaps it was carried out still in the seventeenth century, given the age of the overpaint.

Up close and personal

Dirck van Delen is best renowned for his architectural pieces such as Palace Interior with the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus from 1626 and Interior of a Gothic Church from 1639, both signed. He is known to have painted one still life: Tulip in a Vase from 1637, also signed. Portraits are scarce in his oeuvre; in fact, to date Deathbed Portrait of Pieter van Delen is the only known signed portrait whose subject can be identified. Its intimate, family quality is truly unique: father Van Delen immortalised his deceased first-born (and probably only) child Pieter.

Given that family connection, it seems very plausible that the deathbed portrait was intended for ‘personal use’ and was afforded a place in the interior of Van Delen’s home in Arnemuiden. Most likely, it is one of the 30 succinctly described ‘conterfeytsels’ (‘likenesses’) in the painter’s extensive estate inventory drawn up in July 1671.11 Perhaps it hung in the ‘Camer’ (‘room’) with the green silk upholstered four-poster bed (ledikant), which featured no less than 32 paintings. Besides portraits of family members – of ‘the late Mr. secretary van Swieten and his wife’, ‘his grandfather and his grandmother’, ‘Mr van Delen and one [portrait] of his most recently deceased wife’ – ‘four other likenesses’ are specified.12 Also upstairs ‘in the front room’ where there was a small four-poster bed with green and yellow hangings, hung ‘7 likenesses, both small and large’.13 There, among other things, the painter also kept ‘various drawings and prints by different masters’.14 Furthermore, Van Delen had a particularly rich library: the list of books specifying the author and title takes up no fewer than 21 pages. They include publications on subjects as diverse as religion, antiquity, history, politics, law, agriculture, horticulture, mathematics, accounting, medicine, literature and music. Important art theoretical treatises like Albrecht Dürer’s On Human Proportion and Carel Van Mander’s Book on Picturing also adorned the artist’s bookshelf.15 Furthermore, he owned ‘41 books containing drawings and prints, both small and large’ and ‘388 loose prints’.16 The description of Van Delen’s ‘schilder camertien’ (‘studio’) also reveals much. It included most probably his own work such as ‘a church painted on marble’, ‘a palace on marble’ and ‘an unframed perspective’ as well as ‘4 unfinished paintings, large and small’.17 Also present in the room were several portraits, a map of the world, and a large and a small easel. His painting material was described too: including, a ‘box containing some paints and brushes’, a rubbing stone for grinding pigments, four ‘maulsticks’, three ‘palettes’, three ‘saws, large and small’, a ‘box with some carpenter’s tools’ and a cupboard containing ‘some paints’ and some ‘clutter’.18

Remember you must die

The extraordinary Deathbed Portrait of Pieter van Delen is a fine example of the importance of conducting art-historical research in conjunction with material-technical research. Only by combining the two was it possible to identify both the painter and the little boy portrayed. The panel evolved from an anonymous deathbed portrait into a highly personal effigy that provides a unique insight into the family life of Zeeland artist Dirck van Delen, who actually specialised in architectural paintings. Although not much is known about mourning and grief in the seventeenth century,19, it is not implausible that on the one hand Van Delen wanted to bid farewell to his dead son through the portrait and on the other wanted to immortalise him. In this sense, it is reminiscent of Kinder-lyck (meaning both ‘Child-like’ and ‘Child’s Corpse’), a poem composed by Amsterdam-based writer Joost van den Vondel six years later, in 1632, in relation to the death of his own son Constantijn, who, like Pieter van Delen, died the same year he was born.20 Vondel cleverly wrote the rhyme from the perspective of ‘Constantijntje, ‘t zaligh kijntje’ (‘Constantine, blessed child benign’) who looked down from heaven in wonder at his mother in tears.21 The poet concluded with the consoling words of resignation with which Van Delen also had to contend: ‘Eeuwigh gaat voor oogenblick’ (‘Moments yield to endlessness’). After all, earthly life is finite and fleeting, the afterlife eternal – it is the typical Baroque idea of vanitas. The fact that Van Delen was fully aware of that is also illustrated by the funerary hatchment he had made featuring the names of his three deceased wives.22 At the bottom is the unmistakable text: ‘Gedenckt te Sterven’ (‘Remember you must die’). Pieter van Delen is not mentioned on that memorial. He had already been immortalised by Dirck van Delen in 1626, as The Phoebus Foundation’s deathbed portrait shows. And thanks to the discovery of the hidden inscription, the memory of that little boy has lived on for almost four hundred years through his father’s portrait.

How to cite this item?

L. Kelchtermans, ‘Extraordinary Deathbed Portrait by Dirck van Delen’, Phoebus Findings, https://phoebusfoundation.org/en/phoebus_findings/5/, accessed on [dd.mm.yyyy].

All rights reserved. No part of this Phoebus Finding may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from The Phoebus Foundation. If you have comments or want to make use of our images, we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: info@phoebusfoundation.org

Footnotes

- This Phoebus Finding is part of the author’s research on pregnancy and motherhood in the early modern period.[↩]

- Paris, Tajan, 22.06.2022, lot 35.[↩]

- For more information on restoration and image analysis techniques, see S. Van Dorst (ed.), Crazy about Dymphna – The Story of a Girl who Drove a Medieval City Mad, Veurne, 2021.[↩]

- Many thanks to Adri Verburg for carrying out these analyses and to Sven Van Dorst for interpreting the technical analyses and the findings of Eva Van Zuien who restored the portrait in The Phoebus Foundation’s studio.[↩]

- Many thanks to David Lainé (IPARC) for carrying out these analyses and for reconstructing the original inscription in cooperation with Sven Van Dorst.[↩]

- On his life and oeuvre, see, among others, M.A. Lieveld-van Belzen, ‘Een bekend persoon uit Arnemuiden: Dirck van Delen (1)’, Arneklanken, 5, 4 (2000): 33-36; Idem, ‘Een bekend persoon uit Arnemuiden: Dirck van Delen (2)’, Arneklanken, 6, 1 (2001): 18-20; Idem, ‘Een bekend persoon uit Arnemuiden. Een burgemeester van Arnemuiden: Dirck van Delen (3 en slot)’, Arneklanken, 6, 4 (2001): 23-25; B. Haak, Hollandse schilders in de Gouden Eeuw, Zwolle, 2003: 342-343; P.J. Feij, ‘Dirck van Delen (1605-1671) (1)’, Arneklanken, 10, 2 (2005): 11-18; Idem, ‘Dirck van Delen (1605-1671) (2)’, Arneklanken, 10, 3 (2005): 12-19; K. Heyning, Zeeuwse meesters uit de gouden eeuw, 2nd edition, Zwolle, 2022: 76-77.[↩]

- Middelburg, Zeeuws Archief (MZA), Verzameling Doop-, Trouw-, Begraaf- en Lidmatenregisters Zeeland, access no. 995, inv. ARN-6, Trouwboek 1625-1731, dated 23.08.1625; Idem, inv. ARN-8B, Lidmatenregister 1610-1682, dated 28.09.1625.[↩]

- MZA, Verzameling Doop-, Trouw-, Begraaf- en Lidmatenregisters Zeeland, access no. 995, inv. ARN-8A, Trouwboek 1651-1716, dated 1651 and 26.12.1658; Lieveld-van Belzen 2000: 33; Lieveld-van Belzen 2001: 23-24.[↩]

- MZA, Verzameling Doop-, Trouw-, Begraaf- en Lidmatenregisters Zeeland, access no. 995, inv. ARN-1, Doopboek 1593-1627, dated 12.08.1626.[↩]

- Maria van Delen, presumably a niece of the painter, is mentioned along with her husband Samuel Boone, who was discredited. Lieveld-van Belzen 2001: 23; P.J. Feij, ‘Dirck van Delen, begaafd architectuurschilder, creatief boekhouder en corrupt licentmeester’, available online via http://www.arnehistorie.com/Artikelen-Bekende-personen-ak/dirck-van-delen-begaafd-architectuurschilder-creatief-boekhouder-en-corrupt-licentmeester.html, accessed on 09.08.2023.[↩]

- MZA, Rechterlijke archieven Zeeuwse Eilanden, access no. 10, inv. 180i, no. 4: ‘Delen, Dirck van, inventaris, 1671, juli 11 en 25’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘wylen dh.r secr[etari]s van Swieten en syn huysvrouwe’, ‘syn grootvader en syn grootmoeder’, ‘dh.r van Delen en een [portret] van syn laest overleden huysvrouwe’, ‘vier andere conterfeytsels’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘boven op de voorcamer’, ‘7 conterfeytsels soo cleen als groot’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘v[er]scheyde teyckeningen en printen van v[er]scheyde meesters’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘Durer van de menschelycke proportie’, ‘schilder bouck van Carel V[an]mander’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘41 boucken met teyckeningen en prenten soo cleen als groot’, ‘388 losse prenten’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘een kerck geschildert op marbersteen’, ‘een paleysjen op marmbersteen’, ‘een perspectyf sonder lyste’, ‘4 onvolmaeckte schilderien soo groot als cleen’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘doose met eenige verwe en pinceelen’, ‘schilder stocktjes’, ‘palletten’, ‘sagen soo groot als cleen’, ‘back met eenige timmermans gereetschap’, ‘een vaststaent casken daer in eenige verwen en voorts rommelinge bevonden’.[↩]

- More information on this subject can sometimes be obtained from egodocuments or poems. For instance, Peter Paul Rubens wrote of his grief almost a month after the death of his first wife Isabella Brant in a letter dated 15 July 1626, to the French archivist Pierre Dupuy. The grieving Constantijn Huygens also composed the sonnet Op de dood van Sterre (‘On the Death of Sterre’) in relation to the passing of his wife Susanna van Baerle. L. Huet, De brieven van Rubens, Antwerp/Amsterdam, 2006: 146-147: ‘Maar ik vind het heel moeilijk om de smart van het verlies te scheiden van de herinnering aan de persoon die ik zolang ik leef moet liefhebben en eren’ (‘But I find it very difficult to separate the anguish of loss from the memory of the person I must love and honour for as long as I live’); N. Büttner, Rubens. De schilder van mythen en goden, translated from German by Paul Heijman, Amsterdam, 2017: 100-101; F.R.E. Blom and A. Leerintveld, ‘“Vrouwen-schoon met Mannelicke reden geluckigh verselt”. De perfect match met Susanna van Baerle’, in: E. Kloek, F. Blom and A. Leerintveld (ed.), Vrouwen rondom Huygens, Hilversum, 2010: 107.[↩]

- Van Delen undoubtedly knew Vondel’s work because his library contained ‘Vondel van de helden godts’ and ‘J: van Vondels Palemedes’. MZA, Rechterlijke archieven Zeeuwse Eilanden, access no. 10, inv. 180i, no. 4: ‘Delen, Dirck van, inventaris, 1671, juli 11 en 25’.[↩]

- Vondel’s poem in full: ‘Constantijntje, ‘t zaligh kijntje, / Cherubijntje, van om hoogh, / D’ydelheden, hier beneden, / Vitlacht met een lodderoogh. / Moeder, zeit hy, waarom schreit ghy? / Waarom greit ghy, op mijn lijck? / Boven leef ick, boven zweef ick, / Engeltje van ‘t hemelrijck: / En ick blinck ‘er, en ick drincker, / ‘t Geen de schincker alles goets / Schenckt de zielen, die daar krielen, / Dertel van veel overvloets. / Leer dan reizen met gepeizen / Naar pallaizen, uit het slick / Dezer werrelt, die zoo dwerrelt. / Eeuwigh gaat voor oogenblick’. J. van den Vondel, J.F.M. Sterck, H.W.E. Moller et al., De werken van Vondel, deel 3: 1627-1640, Amsterdam, 1929: 388. Translated into English: ‘Constantine, blessed child benign / Cherub mine, sees from on high / Pomp and show in man below, / Therefore laughs with twinkling eye. / ‘Mother’, said, ‘Lo, wherefore fret so / Why regret so by my corpse? / I’m alive here, I survive here / Angel-child in heav’nly courts: / Brightly gleaming, sprightly cleaning / All the bounteous Giver showers / And unfolds on myriad souls, / Wanton with such lavish dowers. / Turn your face then and so hasten / To this place thence from the mess / Made on earth, of little worth. / Moments yield to endlessness’. P. King, ‘Three Translations of Vondel’s ‘Kinder-lyck’, Dutch Crossing. Journal of Low Countries Studies, 3, 8 (1979): 82-83. See also M.B. Smits-Veldt and M. Spies, ‘Vondel’s Life’, in: J. Bloemendal and F.-W. Korsten, Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679): Dutch Playwright in the Golden Age, Leiden/Boston, 2012: 66.[↩]

- The full text of the commemorative plaque, now located at Museum Arnemuiden: ‘DIRCK VAN DELEN heeft dit opgerecht ter gedachtenis sijner weerde en[de] lieve huysvrouwen. MARIA VANDER GRACHT. oudt synde 62 Jaren overleden den 30 Augustus 1650. Ende CATHARINA DE HANE, overleden den 4 December 1652 oudt sijnde 34 Jaren. midtsgaders IOHANNA VAN BAELEN, oudt 68 Jaren overleedt den 16 December 1668. DIRCK VAN DELEN. OVERLEDEN. DEN. 16. meij 1671. OVDT SYNDE. 66. JAREN, Gedenckt te Sterven’ (‘Dirck van Delen established this in memory of his beloved wives. Maria van der Gracht, died at the age of 62 on 30 August 1650. And Catharina de Hane, died on 4 December 1652 at the age of 34, and Johanna van Baelen, died at the age of 68 on 16 December 1668. Dirck van Delen died on 16 May 1671 at the age of 66. Remember you must die’). For an image of the plaque, see MZA, Beeldbank, Stadhuiscollectie Arnemuiden, no. 13, https://hdl.handle.net/21.12113/D4F0C6F1896049D9AE3A55971F27E740, accessed on 09.08.2023.[↩]