Europa with Balls: The Abduction of Elisabeth Catharina Schut

Dr Leen Kelchtermans

Shortly after his return from Italy, the Antwerp master Cornelis Schut painted the Abduction of Europa, an impressive scene based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses (II: 868-875).1 Europa anxiously fixes her gaze on the shore as she is carried off into the sea by the supreme god Jupiter, disguised as a ferocious white bull. Her handmaidens try and save the Phoenician princess, but it all happens so fast, illustrated by her raised arm, flowing robes, billowing hair and the broken string of pearls around her crown. The little putto who heroically tries to hold on to her with a ribbon is also tossed aside. Alas, the beautiful Europa was deceived by infatuated Jupiter’s sweet ruse.

The hairy hide of the powerful bull, the play of light and dark on the skin of the frightened princess, and the subtle hues of colour in the drape of her garments enhance the scene. This all came to light following the painting’s recent conservation treatment at The Phoebus Foundation’s restoration studio. As a result, the work is resplendent once more, just as Schut intended. When he began working on it, Schut roughly sketched the composition onto the canvas in colour. During the painting process he decided to make a few changes. He altered the hands of Europa and her handmaidens, and initially envisaged the bull’s nose more to the right.2 When Schut applied the finishing touches to his Abduction of Europa, he couldn’t possibly have known that his own daughter would experience a similar incident some two decades later.

Her voice

Elisabeth Catharina was baptised on 6 December 1634, in St James’ Church, Antwerp, the daughter of ‘Mr Cornelius Schut’ and ‘Miss Catharina Geensins’.3 Her mother died when she was three years old, and just a few months later she had a stepmother, Anastasia Scelliers.4 As a teenager, she received a decent education, for in 1649, her father requested permission to spend two hundred guilders of interest annually on her education.5

In his impressive Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche schilderschool (1883), archivist Frans Jozef Van den Branden was the first to provide the remarkable account of Elisabeth Catharina’s abduction.6 On 31 July 1651, at the age of sixteen, she was abducted for one night by ‘a certain rake, Melchior de Hase’.7 Van den Branden was writing from her father’s point of view. The latter made every effort to rid himself of the blame the incident placed on his family. Van den Branden described Schut’s daughter as ‘well-to-do’, because her mother’s sisters left her a substantial inheritance, but also called her ‘extremely weak’.8 Although his book still serves as a standard and is downright admirable considering the number of archival documents he processed – in a pre-digital era –, the archivist did not always include accurate references for his sources. Recently, several notarial deeds relating to the event were unearthed. Notably, they reveal that it was not so much Cornelis Schut, as Van den Branden suggested, but rather his daughter herself who is speaking.

Events leading up to the incident

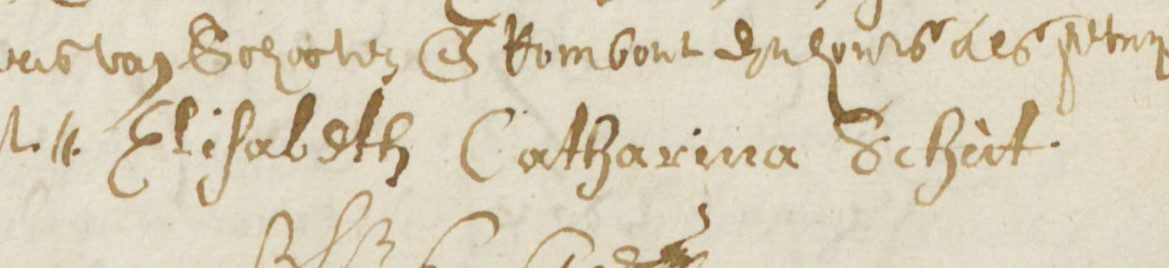

The seven notarial deeds that were traced can be dated between 2 August 1651, and 1 October 1652. Most are statements by Elisabeth Catharina Schut, as well as testimonies of those involved that were recorded at her request. This means the following factual reconstruction only tells her side of the story.

It all began in February 1651, when Elisabeth Catherina went to confession with Father De Haze. Afterwards, he asked how she envisaged her future: did she want to enter a convent or get married? She replied that she wasn’t sure yet, because at sixteen years old, she was still ‘too young’ to take a final decision.9 About five months later, the priest repeated the question and received the same answer, to which he indicated that he did know of a good match for her. This was probably no coincidence, because in mid-July 1651 – on the Sunday of the procession to mark the four-hundredth anniversary of the Holy Scapular – Elisabeth Catharina met her cousin, the wife of bookbinder Cornelis Neefs, at the Carmelite monastery’s church.10 They decided to take a stroll, and as they passed the De Haze family home, her cousin asked if Elisabeth Catharina had already received a marriage proposal. Because some time ago, ‘a young man, a courteous fellow’ had asked her about the painter’s daughter.11 He was also curious about who her confessor was. When she told him it was Father De Haze, the young man had said, ‘that’s rather fortunate because he is our good friend.’12 Therefore, it is highly likely that the courteous fellow was Melchior De Haze. He probably was the nineteen-year-old son of merchant Pedro De Haze and Anna De Haze (his relative?) who lived in Wolstraat, not too far from the house Het Gulden Pansier that Cornelis Schut rented in Paddengracht.13 Soon after, Elisabeth Catharina received several letters from Melchior via the maid who worked at her home. She sometimes went to collect them from her cousin’s house. When Elisabeth Catherina asked her confessor if Melchior De Haze was the good match he had spoken of previously, he claimed he had no idea what she meant.14

The extent to which her confessor was involved is not clear. But it seems very likely that certainly Melchior De Haze, Elisabeth Catharina’s cousin and her maid had jointly devised a cunning plan to convince her to run away from home and marry Melchior against her parents’ will. Indeed, in one of his letters, the young man wrote that he had repeatedly asked Cornelis Schut and his wife for her hand. They refused each time; according to him, because they considered Elisabeth Catharina still a ‘child’ and ‘had also spoken with much malice and contempt for her’.15 Her cousin and maid even managed to delude her into thinking that her parents secretly envisaged a religious future for her and would never give her permission to marry anyone.16 When Elisabeth Catharina herself wanted to ask her parents whether she had actually received many marriage proposals from Melchior, the maid threatened her that if she did, she would be taken to Holland and locked up there. She also took back Melchior’s letters after Elisabeth Catherina had read them and burned three of them in her presence. She presumably wanted to prevent the painter’s daughter from having any evidence and, consequently, from telling her father and stepmother anything about the matter.

Abduction

Running away from home, of course, is quite an endeavour. A plan is needed, even Elisabeth Catherina’s conniving entourage knew that much. The first idea was that the painter’s daughter ‘would leave’ with Melchior on Sunday, 30 July, the day of the St James procession.17 However, she refused. The maid used a whole series of threats to try and change her mind. She did not understand ‘why she was so foolish not to run away then’, because if she continued to reject Melchior, there would be consequences.18 She even persuaded the girl to write a promise of marriage. If she did not, there would be ‘major row’ because the bishop, the dean’s assistant and ‘officiael’ of the city were involved.19 When Elisabeth Catherina indicated that she had no idea what to write, the maid knew exactly what to do. She said: ‘come here, and write down what I tell you.’20 And when the girl told her she was afraid, the maid replied briefly that she ‘had to be brave’.21 Still, Elisabeth Catherina continued to refuse, whereupon a new threat emerged: if she did not run away from home, she would be sent to the convent of the Preacheresses or Dominican Nuns.

If the first plan lacked substance and Elisabeth Catherina was not yet sufficiently brainwashed, the second one rectified all that. The maid said that the painter’s daughter ‘should be prepared and ready on St Ignatius’ Day [Monday, 31 July 1651], and while her mother sat in the confessional, a spiritual daughter would come to her in the church of the English College and lead her away.’ She stressed that ‘she would have to go with her without any arguments’.22 Things turned out a little differently. The two did not go to the Jesuit Church they had agreed upon the morning of that fateful day, but after noon. Was it a spontaneous change of plans by her (unwitting?) stepmother or was it a brave attempt to escape by Elisabeth Catherina? We will probably never know. Anyway, it turned out to be a mere stay of execution: when she went outside after the sermon, the painter’s daughter was still escorted away.23

The spiritual daughter in charge of that was the sister of Melchior De Haze. She took Elisabeth Catharina by carriage to their parental home in Wolstraat. There she explained that she had gone to confession (and rightly so!) to Father Happaert that morning and had told him about the ‘ambush’.24 The plan was to take Elisabeth Catharina away from her reluctant parents so that her brother could marry her. Father Happaert had said he would pray for the plan to succeed, and if it was effective, he did want to be thanked personally in return.

Melchior was also there that evening. He stated that he ‘would keep her in the house that night and in the meantime have someone talk to her father to obtain his consent for them to get married’.25 If he did not agree, he would leave Antwerp with her the next morning so they could get married elsewhere. That was their first – not particularly romantic – altercation, for Elisabeth Catharina indicated in one of her statements that Melchior, other than in his letters, ‘before the date of the aforementioned abduction, never spoke to her’.26 In fact, he should have, because evidently he didn’t even know exactly how old she was. When her age was brought up at the De Haze home and the abducted girl was asked about it, she answered truthfully that she would turn seventeen on St Nicholas’ Day. Her cousin, who apparently was also present, vehemently contradicted her, claiming – albeit misinformed – that she would definitely turn eighteen.14

Denouement

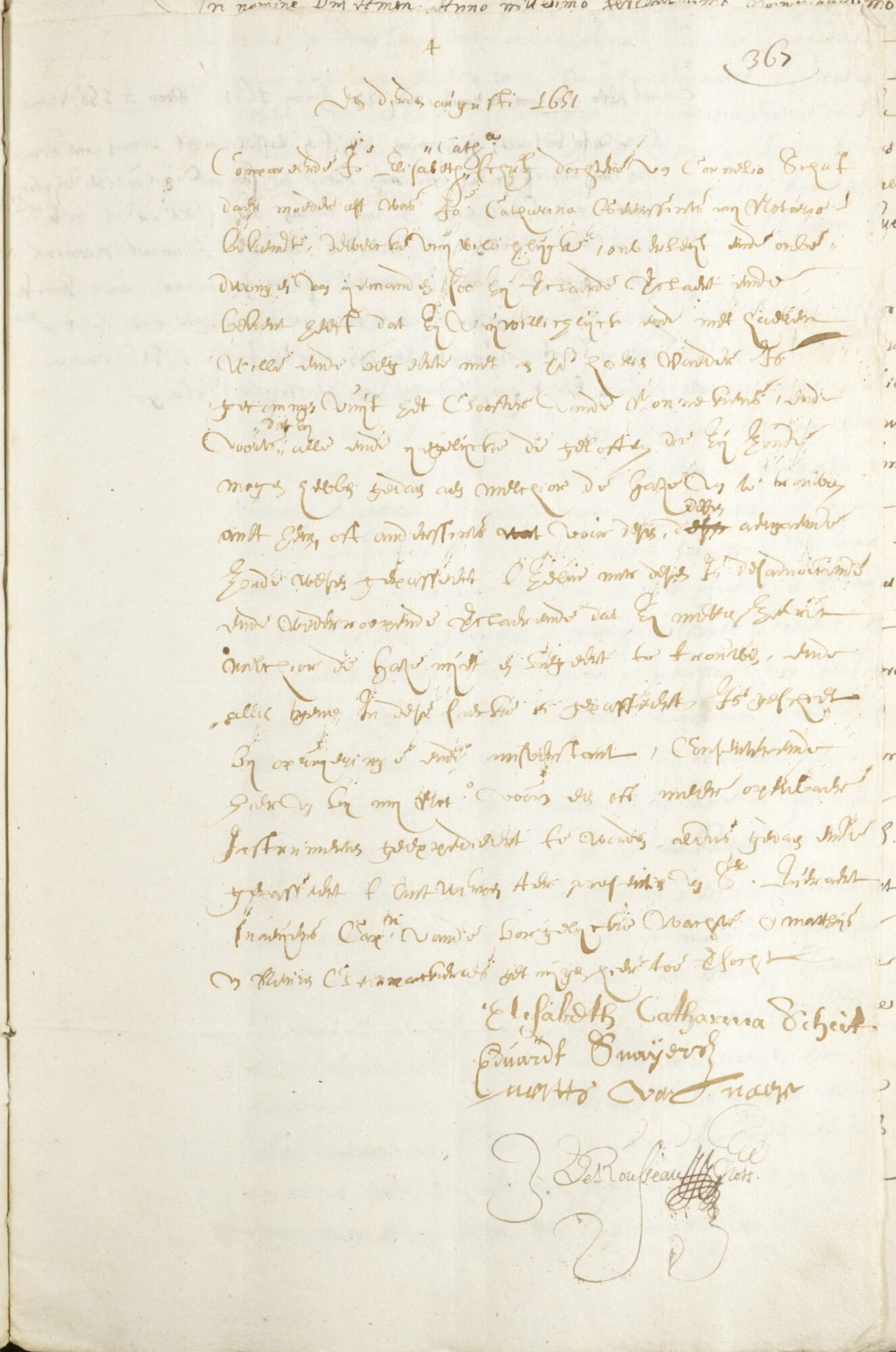

What happened in Pedro De Haze’s home on the night of 31 July is a mystery. What is certain is that Elisabeth Catharina was removed from the house shortly thereafter and was placed under guardianship by the officiael in the ‘convent of nuns’.27 After all, she had made a promise of marriage, and the whole incident needed to be investigated further. On 2 August, Elisabeth Catharina stated that Melchior had visited her there in the morning and threatened her: that he would prevent her from returning to her father, would ‘trample her under his feet and have her detained’.28 A day later, she testified in the presence of her relative, the painter and captain of the civic guard Eduard Snayers, that she had left the convent voluntarily and with her father’s permission. She adamantly refuted ‘the promise of marriage she might have made to Melchior de Haze’ and declared that she ‘did not want to marry him, and that all these matters happened as a result of troublemaking and misunderstanding’.29

But ‘no’ clearly did not (yet) feature in Melchior’s vocabulary. Two weeks later, he was already fervently proposing marriage again – albeit this time in a more civilised manner, through the pastor of St James’ Church Franchois Vanden Bossche. The latter had gone to Cornelis Schut’s house on 17 August 1651, at his request, to ‘find out and examine’ whether ‘Miss Elizabeth Schut’ really didn’t want to become Melchior’s spouse. His findings were crystal clear: ‘the daughter was in no way inclined to marry him.’ Even if her parents did agree to the marriage, the answer was still ‘no’, or in Elisabeth Catherina’s words, ‘I equally wouldn’t want to marry him.’ Thereupon she also mentioned ‘some of the offences she had to endure because of the young suiter who had been accusing her behind her back of being inconstant’.30

Elisabeth Catharina wanted nothing more to do with Melchior. This was also established by notary Jacques Le Rousseau when he was summoned at 8 a.m. on 31 August, by Maximilianus Happaert, the officiael of the diocese of the city of Antwerp (and probably the one who had prayed for the success of the plan to abduct her). Elisabeth Catharina was also there, along with her father and stepmother. She asked why they were there, for ‘in the event it was to speak with Melchior de Haze, she had no desire whatsoever to do so.’ When Happaert confirmed, ‘she protested against the injustice that would be inflicted on her since she could not be forced to speak to someone she did not wish to’.31 Happaert demanded that she talked to him in his presence. If she was not willing now, he would compel her to do so another time. And so it happened: not long after that, Elisabeth Catherina had to visit him again, without her parents this time, and meet her captor against her will. Unfortunately, the notary did not record their conversation. But it seems very likely that the obligatory exchange had to do with Melchior’s statement to the then secretary of the Antwerp bishop, François Hillewerven, also in August 1651. Together with his father, he approached him to inform him that he was resigned to Elisabeth Catherina’s decision. He formulated it somewhat differently: ‘in the event the aforementioned appellant [Elisabeth Catharina] duly declares that she does not wish to marry me, Melchior, and that she releases me from the promise made to her to that effect, we will release her from hers.’32 The secretary reported the news that very hour to the bishop who determined that – in the case of Elisabeth Catharina: the forced – promise of marriage had to be lifted in front of the officiael. Most likely that was why she was summoned to Happaert on 31 August, and the reason for the discussion was much more positive than she had initially expected.

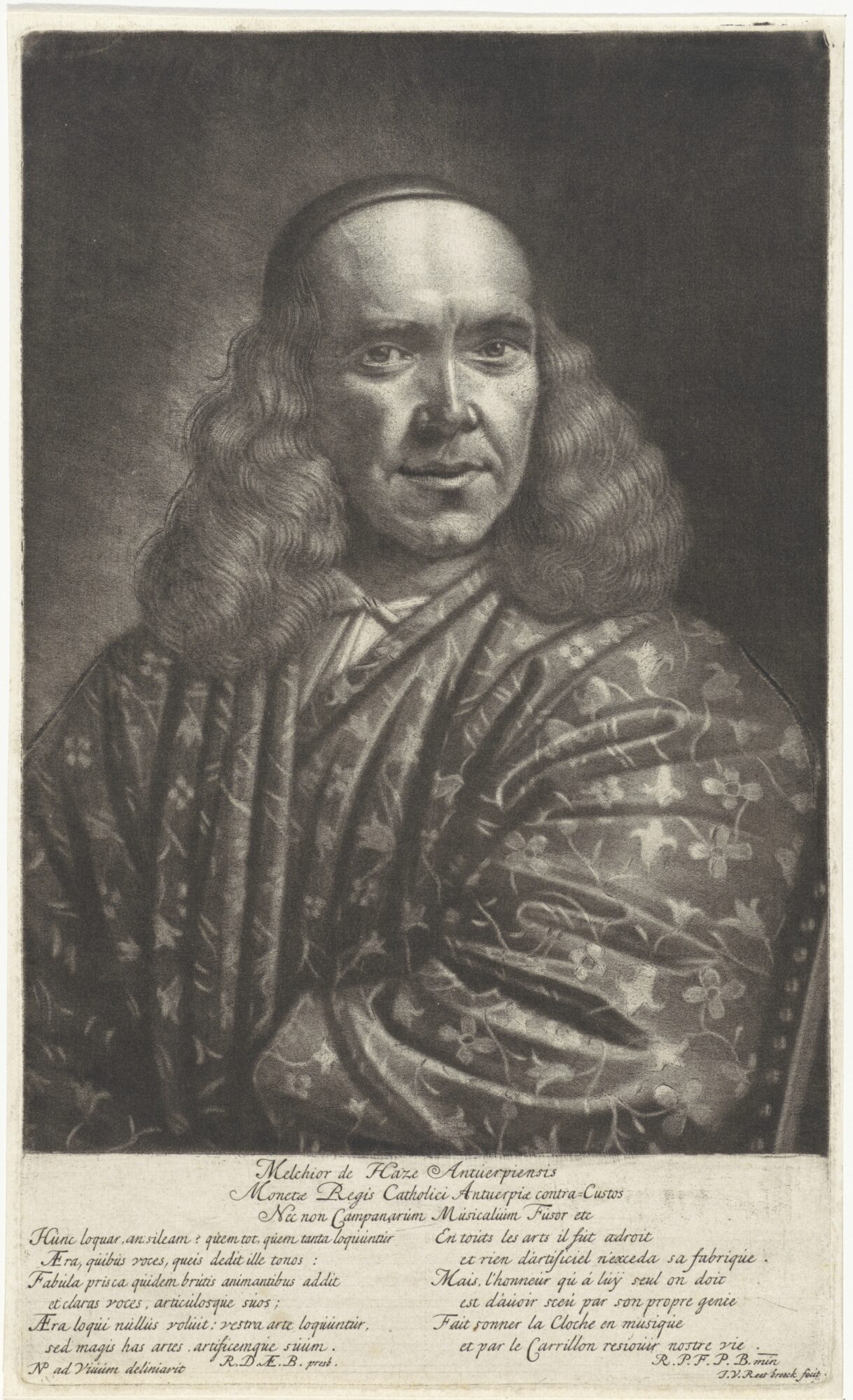

Hillewerven gave his testimony at the request of Elisabeth Catharina on 1 October 1652. A month later, on 3 November 1652, she married Guillelmo Huijmans in Brussels, captured in a portrait drawn by her father in 1647, who held the distinguished position of ‘controller of His Majesty’s water toll’.33 When his daughter married, Cornelis Schut had already left Antwerp more than six months earlier. Perhaps De Haze’s defamation was the reason why he settled in a country estate with a painter’s studio in Borgerhout.34 Just six years later, Melchior De Haze dared propose again: on 25 October 1658, he married Anna Janssens van Dijck.35 He made a career as a bronze and bellfounder.

Antwerp’s Europa?

Printmaker Rombout Eynhoudts acted as a witness to one of Elisabeth Catharina’s statements at Cornelis Schut’s home shortly after the abduction, on 2 August 1651.14 It was him too who produced an engraving after Schut’s Abduction of Europa probably in the 1630s, only a few details of which differ from the version in The Phoebus Foundation’s collection. Below his print, he added a very fitting Latin inscription:

‘Mollia si molli, si dulcia prorsus Amori / Propria, quid præfert Iupiter ora bovis? / O Deceptor Amor! nimium ne crede puella, / Tendit Amor casses, quo minus ipsa putes.’

‘If tenderness is inherent to tender love, if sweetness in short is inherent to that sweet love, why does Jupiter opt for the mouth of an ox? Ah, deceitful love! Don’t believe him too much, young lady. Love devises ruses so you pay less heed.’36

Elisabeth Catherina should have been more critical as well. After all, why did she trust her cousin and maid more than her own father? Why didn’t she talk to him about it, and what does this say about their relationship? What was in Melchior’s letters? Was he just after her inheritance, or was he really in love? And was Elisabeth Catherina initially – before she was threatened – perhaps a little charmed by his advances after all? The notarial deeds give us a glimpse into this early #MeToo story, but at the same time, remain agonisingly vague.

Even though she was abducted, Elisabeth Catharina was not Antwerp’s Europa. For her, no supreme god as a lover, but a mortal, gallant ‘fellow’. (Perhaps his looks weren’t that bad, so that could possibly still work out.) No ferocious bull that dragged her away, but, far less exciting, a spiritual daughter in a carriage. While Europa’s entourage tried to save her, it was precisely Elisabeth Catharina’s that deceived her. If the painter’s daughter had been tricked, she did not suffer her fate lightly. ‘Extremely weak’ was how Van den Branden described her, but Elisabeth Catharina does not appear weak at all in the notarial records. Indeed, she was the one who, as a minor (!), testifies ‘voluntarily, not having been persuaded or forced by anyone’;37 she was the one who personally signed the deeds, often not even accompanied by her parents, and who resolutely refused to marry her abductor. Although perhaps her parents’ initial refusal was (partly) decisive, it is remarkable to hear the voice of the assertive teenage girl in the documents. She fiercely defended herself: she did not want to enter a convent, refuted to speak nor marry a man with whom she did not desire to, and moreover had never wanted to – after all, she had not acted freely; she had been manipulated. Elisabeth Catherina stood up for her untarnished reputation, which was absolutely essential. For an early modern girl, her virginity was her greatest virtue, as poet Jacob Cats emphatically described using all sorts of metaphors in his instructive books. The slightest suspicion that she had been deflowered or lost her cherry meant she would belong to a group of dubious girls whose marriage partners offered fewer prospects and a less favourable future.38 So the stakes were high. Perhaps hence relatively soon after she was released from her false promise of marriage, she wed the distinguished Huijmans and, just to be sure, did so outside Antwerp. Furthermore, regardless of what may or may not have happened during the night she was abducted, she was dismissed as inconstant when, as her testimonies show, she certainly was not. Elisabeth Catherina was a duped Europa, but one with balls.

How to cite this item?

L. Kelchtermans, ‘Europa with Balls: The Abduction of Elisabeth Catharina Schut’, Phoebus Findings, https://phoebusfoundation.org/en/phoebus_findings/6/, accessed on [dd.mm.yyyy].

All rights reserved. No part of this Phoebus Finding may be reproduced, stored in an information storage and retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from The Phoebus Foundation. If you have comments or want to make use of our images, we’d like to hear from you. Contact us at: info@phoebusfoundation.org

Footnotes

- G. Wilmers, Cornelis Schut (1597-1655). A Flemish Painter of the High Baroque, Pictura Nova, 1, Turnhout, 1996: 30, 32, 73-74.[↩]

- The conservation treatment was carried out by Jill and Ellen Keppens between August 2022 and January 2023. J. Keppens & E. Keppens, Restauratiedossier ‘Ontvoering van Europa’ – Cornelis Schut, unpublished report, 2023: 4-5.[↩]

- Antwerp, Felixarchief (AFA), Parochieregisters, St James’ Church Baptisms, PR#49, fol. 109v: ‘S.or Cornelius Schut’, ‘Jouff. Catharina Geensins’.[↩]

- F.J. Van den Branden, Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche schilderschool, Antwerp, 1883: 762 (lists 29 September 1637 as the date of death); P. Rombouts & T. Van Lerius, De Liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche Sint Lucasgilde, onder zinspreuk: ‘wt ionsten versaemt’, Antwerp, [1864-1876]: vol. 2, 69 (lists 29 December 1637 as the date of death); Wilmers 1996: 17, 19.[↩]

- L. Kelchtermans, ‘Portret van een zeventiende-eeuwse schildersvrouw: Anna Schut, huisvrouw en weduwe van Peter Snayers’, Oud Holland, 126, 4 (2013): 184.[↩]

- Van den Branden 1883: 763-764. See also Wilmers 1996: 22-23.[↩]

- Van den Branden 1883: 763: ‘zekere losbol, Melchior de Hase’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘bemiddeld’, ‘uiterst zwak’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163r-v (quote ‘te jonck’ on fol. 163r).[↩]

- This is possibly Margareta Artsens who married ‘Cornelius De Neef’ on 5 February 1628. AFA, Parochieregisters, Church of Our Lady South Marriages, PR#197, p. 41. That year could be consistent with the registration of ‘Cornelis Neefs, bookbinder’ (‘Cornelis Neefs, boeckbinder’) in the Liggeren (‘Ledgers’) of the Antwerp Guild of St Luke: in 1620-1621 as an apprentice and in 1631-1632 as a master. Rombouts & Van Lerius [1864-1876]: vol. 1, 565-566; vol. 2: 31. In September 1617, ‘Cornelius Neefs’ enrolled as a member of the Sodality of the Bachelors. Antwerp, Erfgoedbibliotheek Hendrik Conscience, Register der inschrijvingen in de Sodaliteit der meerderjarige jongmans onder den titel Geboorte van O.-L. Vrouwe, te Antwerpen [1608-1772]: fol. 17v.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 404r-v (quote ‘een Jongman, eenen galanten baes’ on fol. 404r).[↩]

- Idem, fol. 404r: ‘dat is goet want dat is onsen goeden vrient’.[↩]

- AFA, Parochieregisters, Church of Our Lady North Baptisms, PR#33, fol. 110v (5 June 1632); Idem, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163r; Wilmers 1996: 17.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163v.[↩][↩][↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 543r-v (quotes ‘kint’ and ‘veel meer ander quaet van ende misachtingen v[an] haer gesproken hadden’ on fol. 543v).[↩]

- Idem, fol. 543r.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 404v: ‘zoude deurgaen’. The St James procession took place on the first Sunday after the patron saint’s celebration on 25 July. S. Beghein, Kerkmuziek, consumptie en confessionalisering. Het muziekleven aan Antwerpse parochiekerken, c. 1585-1797, doctoral dissertation, University of Antwerp, 2014: 79-80. Since 31 July 1651 was a Monday, as mentioned in Elisabeth Catherina’s testimony of 2 August 1651, 25 July was a Tuesday and the St James procession was organised on Sunday 30 July. AFA, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163r.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 404v: ‘waeromme zij zoo sot was dat zij alsdoen nijet door en gincke’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘groote rusie’. An ‘officiael’ was an official in charge of administering clerical justice. See the entry in the Geïntegreerde Taalbank, https://gtb.ivdnt.org/iWDB/search?actie=article&wdb=VMNW&id=ID33782&lemma=officiael&domein=0&conc=true, accessed on 09.02.2024.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 404v: ‘comt, schrijft gij, ick zalt u dicteren’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘couragie moeste nemen’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 449r: ‘haer dan op Sinte Ignatius dach zoude gereet houden, ende dat als haer moeder zoude sitten inden bichtstoel, datter alsdan in de kercke van het Engelsch collegie eene geestelijcke dochter bij haer zoude commen ende haer wech leyden’, ‘zij sonder tegenseggen met haer zoude gaen’.[↩]

- Idem, fol. 449v.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163r: ‘aenslach’.[↩]

- Idem, fol. 163v: ‘haer voor dijen nacht inden selven huyse souden laten ende ondertusschen haer vader soude doen spreken om sijn consent tot hunne trouwen te hebben’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 449v: ‘voor date van het voorst. wech leyden noijut aengesproken en heeft’.[↩]

- Idem, fol. 163r: ‘gesequestreert’, ‘clooster van nonnekens’.[↩]

- Idem: ‘haer onder sijn voeten soude trappen ende doen vastsetten’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 367r: ‘de geloften die zij zoude mogen hebben gedaen aen Melchior de Haze van te trouwen’, ‘nijet en begeert te trouwen, ende alle tgene in dese saecke is gepasseert, is geschiet by opruyeringe ende misverstant’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2475, fol. 568r: ‘ondersoecken en[de] te examineren’, ‘Jouffrouwe Elizabeth Schut’, ‘dat de selve dochter geene inclinatie oft sin en hadde om den selven te trouwen’, ‘ick en soude hem evenwel niet willen trouwen’, ‘eenighe affronten die den selven iongman haer hadde aengedaen, met achter haeren rugge haer te blameren over haere onstandvastigheijdt’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2474, fol. 423v: ‘ingevalle dat het was om met Melchior de Haze te spreken dat sy den selven in geender manieren en begeerde te spreken’, ‘protesteerde van het gewelt dwelck haer soude geschieden, mits sy nyet gedwongen en conste worden om yemanden te spreken die sy nyet en begeerde’.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Jacob Le Rousseau, N#2475, fol. 572r: ‘ingevalle de voorst. requirante behoorlycken v[er]claert dat zy met my Melchior nyet en begeert te trouwen ende dat zy my ontslaet vande gelofte haer dyenaengaende gedaen, wy zullen haer van gelycken ontslaen’.[↩]

- Brussels, Stadsarchief, Parochieregisters, Church of St Michael and St Gudula Marriages, 1651-1660, fol. 33v; Wilmers 1996: 23: ‘controleur zyne Majesteits water tol’.[↩]

- Van den Branden 1883: 764; Wilmers 1996: 22-23.[↩]

- D. Fagot, ‘Haze, Melchior de’, in: Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek, Brussels, 1966: vol. 2, kols. 287-291; H.B. Van der Weel, François en Pieter Hemony: stadsklokken- en geschutgieters in de Gouden Eeuw, Hilversum, 2018: i.a. 44.[↩]

- Many thanks to Prof Dr Aäron Vanspauwen for the translation.[↩]

- AFA, Notariaat, Notary Willem Le Rousseau, N#2440, fol. 163r: ‘vrywillichlijck, onverleydt ende onbedwongen van yemanden’.[↩]

- J. Cats, Houwelick. Dat is Het gansch Beleyt des ECHTEN-STAETS, Middelburg, 1625: I***ir up to and incl. I****ir (vol. 1: Maeght); J. Cats, Spiegel van den Ouden ende Nieuwen Tijdt, The Hague, 1632: vol. 1, 120-121.[↩]