Behind the Scenes in Tallinn

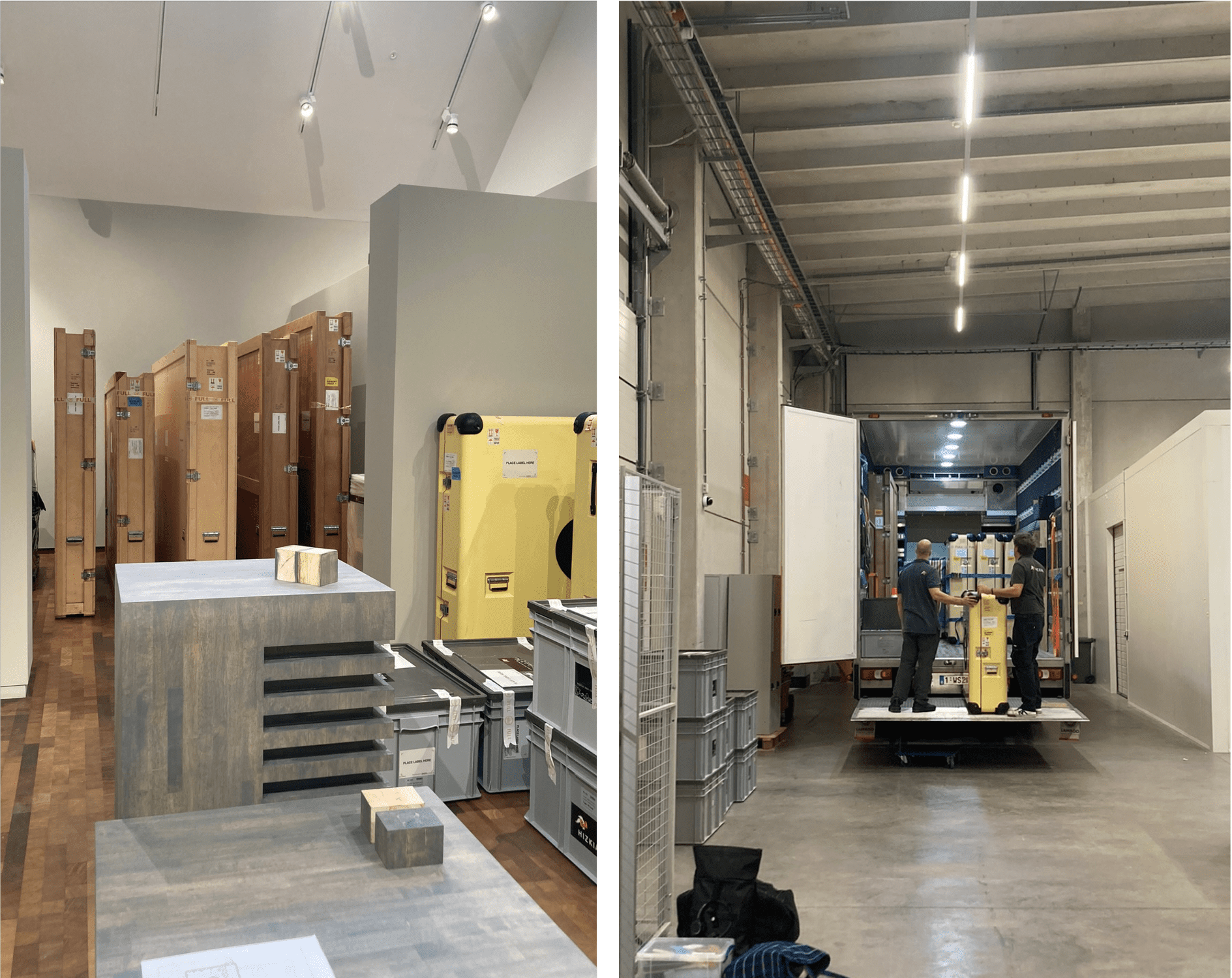

On June 21, 2024, the exhibition History and Mistery: Latin American Art and Europe opened at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn, Estonia. This exceptional installation features 112 Latin American works curated by Sirje Helme and Kadi Polli, whilst offering a unique scenography designed by renowned artist Kristi Kongi. It showcases magnificent works from the Viceroyalties period, alongside a selection of modern artworks by well-known artists such as Joaquín Torres-García, Roberto Matta, and Diego Rivera.

A special space has also been dedicated to the work and life of Leonora Carrington. The Phoebus Foundation has loaned seven works for this part of the exhibition, and the team of curators and project coordinators has traveled to Tallinn to assist with the preparation and installation of these artworks, which are being shown internationally for the first time here.

Special attention has been given to the delicate materials of some artworks, and extensive preparations have been made to ensure the installation proceeds efficiently and safely. Careful restoration has been carried out, and special packaging and installation requirements have been applied. Furthermore, additional security measures have been implemented to protect the artworks from potential vibrations in the space.

History and Mistery: Latin American art and Europe runs until November 3, 2024, and is accompanied by several public events introducing the artistic relationships between Latin America and Europe. For more information and tickets, please visit the museum’s website at kumu.ekm.ee.

Behind the Scenes in Montreal

At the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), a lot of work has been going on behind the scenes over the past few weeks in preparation for the upcoming exhibition Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools, which opens on 8 June 2024. A particularly fascinating aspect of the preparation was the journey undertaken by the artworks, as well as the setup of the exhibition space itself. With dedication and precision, every effort was made to ensure that each artwork would be optimally displayed, allowing the public to enjoy an unforgettable experience.

The artworks from The Phoebus Foundation’s collection have once again crossed the Atlantic Ocean, this time to reach their destination in Montreal, following last year’s stops in Denver and Dallas. In The Phoebus Foundation’s restoration workshop and storage facility, the loaned pieces were meticulously handled and packed in the safest possible manner to ensure they would arrive at the museum without any damage. In total, 130 artworks traveled by plane to Canada, requiring careful coordination and planning for the transport!

Upon arrival at the prestigious Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, after a long journey, the installation of the artworks could begin. Collaborative teams from the museum and The Phoebus Foundation carefully unpacked each piece, followed by a thorough condition check. Although the artworks were packed in airtight and shock-resistant crates, transport is never without risk.

Under the watchful eyes of the restorers and coordinators from both the museum and The Phoebus Foundation, the artworks were carefully installed in their designated places. It is always a significant challenge for curators and scenographers to position the pieces perfectly, ensuring they fit both conceptually and aesthetically within the exhibition space. After a successful installation, the final scenographic adjustments were made, including lighting, signage, and interactive elements.

Behind every exhibition stands a team of curators, transporters, technicians, and other responsible individuals who join forces to bring this vision to life.

Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools runs from 8 June to 20 October 2024. For more information and tickets, visit www.mbam.qc.ca.

Restoration of Wautier’s ‘Bust of a Saint’

Eva van Zuien, independent restorer specialised in old masters, recently completed the restoration of a true artistic gem. Commissioned by The Phoebus Foundation, she breathed new life into Bust of a Saint by Brussels artist Michaelina Wautier.

Michaelina’s distinctive touch is easily recognisable in this beautiful work. The way in which she painted the soft features, the eyes and the drapery embodies her characteristic style. Additionally, the artist signed the work in her typical manner, placing her full first and last name, Michaelina Wautier fecit, in the upper left corner.

The painting was in a moderate condition before treatment. It had been lined in the past, but the edges were damaged, causing the canvas to no longer be adequately stretched on the frame. Furthermore, the paint layers appeared dull due to surface dirt and the presence of a yellowed varnish layer. Notably, a significant portion of the background on the left side of the painting had been subject to overpainting.

Removing the old varnish layer resulted in a notable transformation. Previously obscured original colour nuances, like the blush on the cheeks, became more discernible in the face, and a gradient from light to dark in the background became more visible. The removal of the old overpainting on the left revealed an original underpainting, deliberately left exposed by the artist in a vertical strip. The reason for Wautier’s choice in this matter remains unclear, but it seems that this bust might have been painted on the edge of a larger canvas.

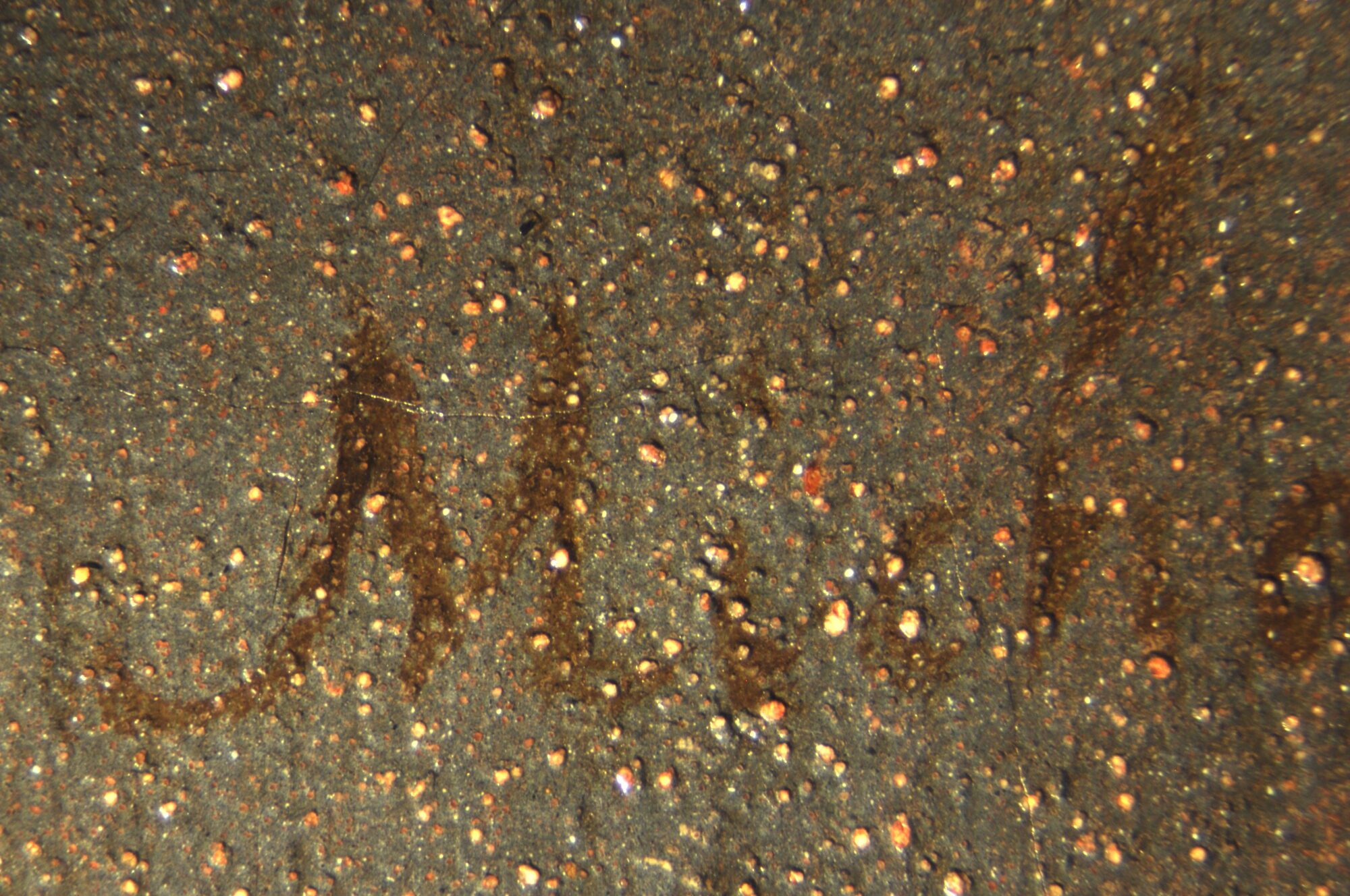

An interesting phenomenon in this painting is the presence of many protrusions on the paint surface. Countless small white crater-like formations are visible throughout the entire work. This is the result of lead soap formation, a chemical ageing process in the paint layer. Considering the disruptive visual effect of these light dots, it was decided to retouch the most distracting ones.

Thanks to this careful restoration, the artwork can once again be admired in all its splendor!

Restoration of ‘Eden’: A Glimpse Behind the Scenes

This month, we take you once again behind the scenes in our restoration studio. Under the guidance of Clara Bondia, Julio Alpuy’s Eden is being prepared for an upcoming exhibition.

Julio Alpuy (1919-2009) was a Uruguayan artist closely associated with Torres García’s inner circle of collaborators. He played a fundamental role in the diffusion of Latin American art in the United States and Europe. His works have been exhibited extensively in galleries and institutions worldwide, attesting to his illustrious career. Painted in 1979, this large-scale oil on canvas is part of a series depicting Eden, featuring a narrative character of naturalistic figures intertwined with depictions of multiple couples.

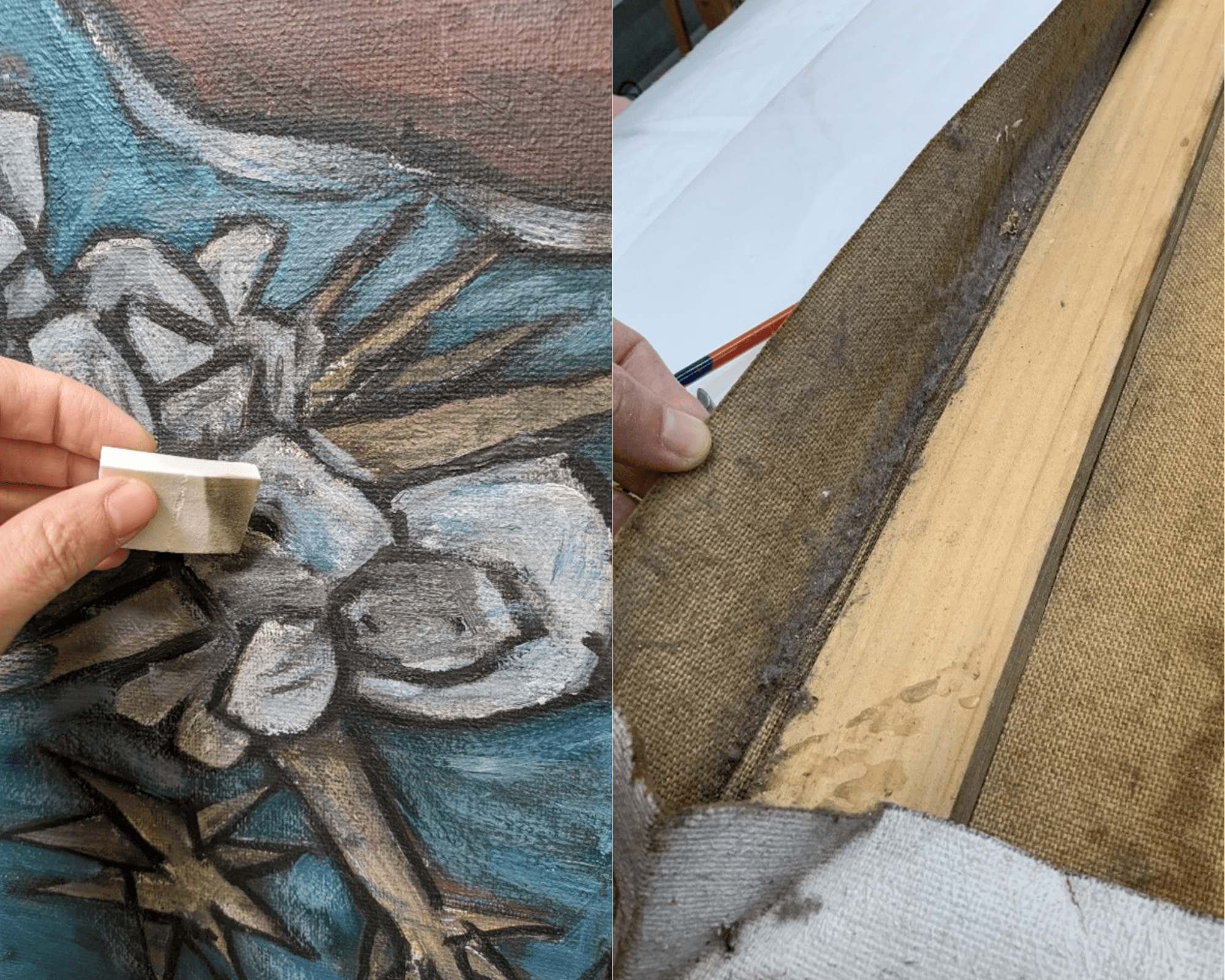

Although the painting was initially mounted on its original stretcher, it quickly became apparent that it did not meet its purpose. The stretcher was not very sturdy due to the thin wooden slats nailed together. As a result, it lacked strength and a movable system to allow for proper tensioning of the canvas, resulting in significant distortions and instability. Additionally, the painting was susceptible to harmful vibrations during any movement or handling, posing a challenge for proper conservation.

Furthermore, the canvas had incurred damage and breakage at the bottom, prompting an earlier restoration attempt. This involved applying a patch crafted from commercially prepared aged canvas, secured with an unidentified synthetic adhesive that had become yellowed and brittle over time. Unfortunately, the patch was visibly marked on the front side, causing a rectangular distortion that hindered the accurate view of the artwork.

After removing the dust, the old patch was treated. The process was highly delicate, but the adhesive was gradually softened and mechanically removed. Additionally, the residue that had penetrated between the fibers was eliminated. The distortion was corrected with controlled weight and humidity, while the original fibers of the canvas were repositioned. Finally, a new reinforcement of synthetic fabric and thermoplastic film layer was applied. As a result, the tear was both volumetrically and chromatically retouched.

As for the stretcher, various options were considered. Ultimately, it was decided to replace it with a new one that meets the requirements necessary for the proper conservation of the artwork. The chosen support is made of high-quality wood with a controlled mobility system.

The artwork was carefully prepared by protecting the edges to prevent potential loss of polychromy during handling. Afterwards, the old stretcher was removed and the back of the canvas was cleaned, removing the accumulated dirt. Subsequently, the artwork was placed onto the new frame and properly stretched to avoid vibrations and aesthetically enhance the accurate representation of the painting.

Curious about where Julio Alpuy’s Eden will be on display? Keep an eye on our website and social media!

Through the art photographer’s lens

In the midst of a bustling schedule filled with numerous projects and publications, these days are also particularly busy in our photo studio. From capturing the intricate details of medieval retables and the timeless allure of baroque portraits to immortalizing the essence of Latin American sculptures, Antwerp postcards, and books of hours, our photographer, Michel, navigates a kaleidoscope of artistic expressions. Each piece demands meticulous attention, often requiring a creative orchestration in order to achieve optimal results.

Aside from capturing a charcoal drawing, Michel focused on photographing two captivating sculptures by Permeke this month: the 1938 pieces titled Bust of a Woman and Niobe. The initial challenge lay in the positioning of these sculptures and prioritizing their safety. Therefore, the decision was made to photograph them horizontally. This choice was inspired by the sculptures’ secure storage space.

Not only the form but also the material from which the sculptures are made posed a unique difficulty: the shiny bronze reflects enormous amounts of light akin to a mirror. While a disguised self-portrait of the photographer might add an artistic touch, it is best avoided for photographs destined for collection registration and publication. To filter out reflection as much as possible, Michel set to work with his lightcube, a white “tent” designed for object photography. Through the strategic use of white cardboard, white cloths and tripods surrounding the artwork, the light cube turned into a small, custom-built photo studio for the sculpture. This process demanded time, presenting the following question: Are all reflections completely eradicated? Does the lighting require softening or repositioning? With each shot, Michel analysed the entire setting.

After capturing the image, meticulous post-processing followed in Photoshop. After all, obtaining the perfect photo requires precise image editing. Photographs with different lighting were combined to create the most natural representation possible. Furthermore, any distracting elements from the background, such as cardboard edges, were skillfully removed.

The end result is truly impressive: the fabric and tent structure are imperceptible, and the photograph is devoid of any distracting reflections. The whole process underscores that photographing a work of art is more than just a quick snap with a camera.

Restoration of the Witches’ Sabbath panel

This month, we take a closer look at the restoration of an intriguing work of art: The Witches’ Sabbath, a 16th-century masterpiece by Frans Verbeek. We focus on the restoration of the oak support, carried out by Brian Richardson, a specialist in the conservation and restoration of wooden objects and furniture.

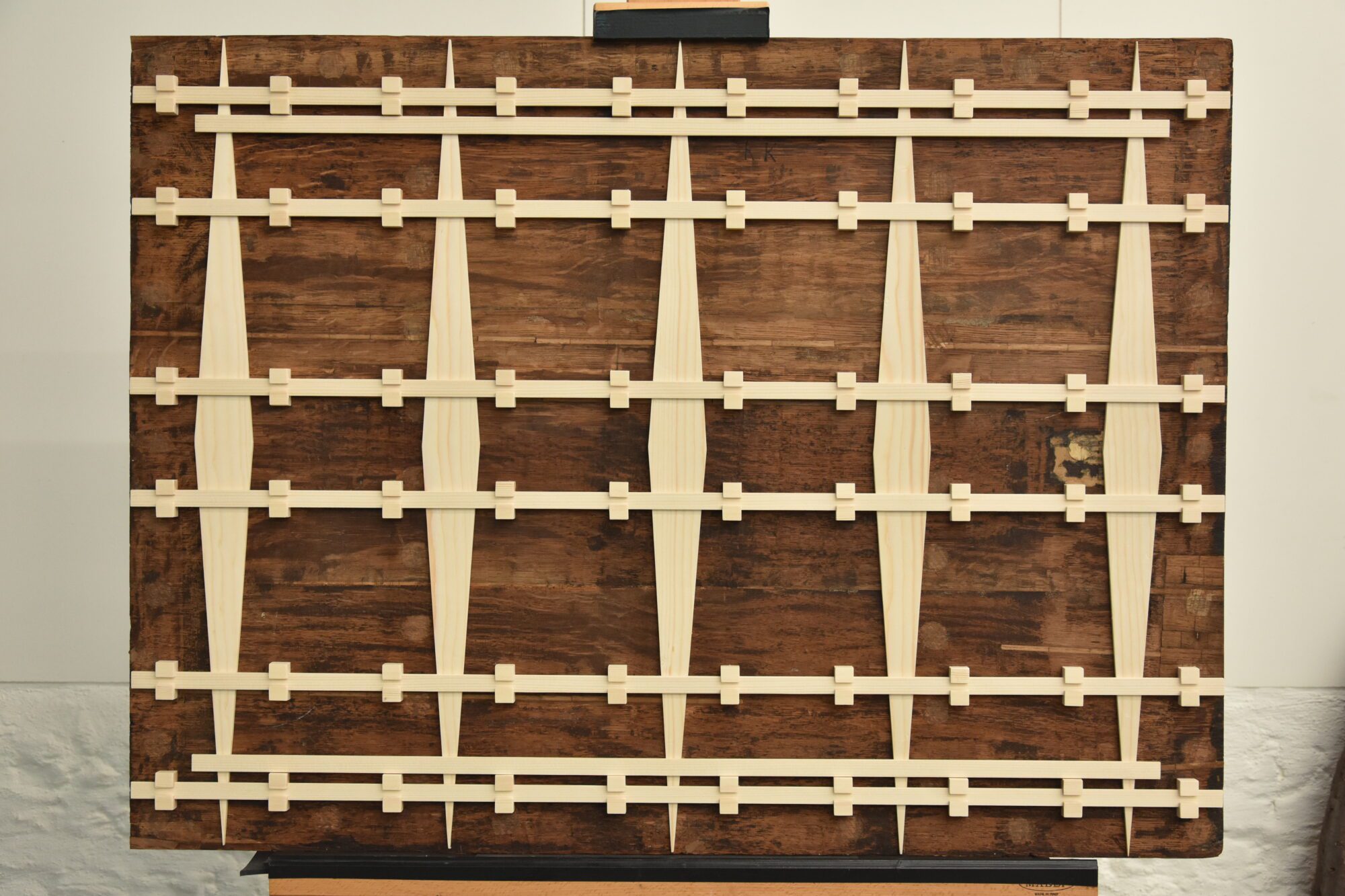

Structure and damage pattern of the wooden carrier

The panel consists of three horizontally oriented oak boards, the top one being 26.5 cm wide, the middle one 21.0 cm, and the bottom one 23.0 cm. This is not clearly visible on the back; during previous restorations, the glue joints were covered with veneer, which made the situation very confusing. It is notable, however, that the panel is only 7 mm thick, which is thin for a panel of this size.

An earlier restoration treatment, presumably from the second half of the last century, included the addition of a support structure at the back to reinforce the panel. Despite the attempt to develop a sprung support structure, the system falls short because the window construction is immobile. Saw marks and serrations in the wood suggest that the panel was thinned, possibly long before the 20th-century support structure. The patina on the backside has been partially removed for the support construction, and the cracks and glue seam have been reinforced with V-shaped inserts in walnut, but not all glueing is even, causing level differences at the front.

Removal of support structure

To improve the condition of the panel, Brian first loosened the support structure, including the screws on the back. He cut away the fastening blocks one by one with a gouge and chisel and finely sanded the panel to smooth the glue residue. The remnants of synthetic glue in the wood structure itself were not removed.

Correction of level difference

After removing the support structure, Brian decided to remove the V-shaped inserts – where the level difference to a crack was most disturbing – to open up the crack and improve the level difference. The expectation was that the V-shaped inserts would follow the cracks nicely. Once the inset pieces of wood were removed, only 2-3 mm would then remain where the crack would need to be loosened. Compresses were used to soak off the glue to then open the crack. Next, Brian carefully cut away the V-shaped inserts on the back with different types of wood chisels. Finally, the white glue, with which the inserts had been glued, was soaked loose with acetone and removed so that the notches were completely clean.

New construction

Without support, the panel was too fragile, so Brian placed a new support structure on the back. This system consisted of slats that were glued to the back with fish glue using small blocks. Each slat was slid into grooves in the blocks, creating an equal distribution of pressure across the backside. After this addition, the panel became considerably more stable and again manipulable.

The Restoration of Archduke Maximilian and Archduchess Elisabeth’s Portraits

Paris-based paintings conservator Perrine de Fontenay, has been a fellow at The Phoebus Foundation for the past three months. Her focus during this period has been on the conservation of paintings from our collection of Latin-American art of the colonial period and our old masters collection. One of her most notable contributions involves working together with paintings conservator Sofia Hennen on two paintings by Jakob Seisenegger (1505 – 1567) depicting the siblings Archduke Maximilian (1527 – 1576) and Archduchess Elisabeth (1526 – 1545).

For the past few months, a long process of painstakingly removing old overpaint has been carried out in order to unveil the original, colourful background intended by the artist.

Jakob Seisenegger (1505 – 1567) painted the portraits in 1537, depicting the siblings Archduke Maximilian (1527 – 1576) and Archduchess Elisabeth (1526 – 1545) at the ages of 10 and 11, respectively. These oil paintings on linden or poplar panels showcase the children adorned in luxurious clothing embellished with jewels and flowers in their hair. The attire and jewels are detailed with gold accents. Both figures are positioned behind a green marble ledge. Initially, the backgrounds were dark brown-black, but in some areas, traces of a colourful layer beneath were revealed after removing oxidized varnishes and tinted layers.

As the court-appointed painter to Ferdinand I, Seisenegger created numerous portraits of the children and other members of the Habsburg court. His artistic skills were highly sought after at the time. Receipts related to Seisenegger’s first commissions from Ferdinand I have been discovered, revealing the artist’s meticulous approach in selecting and preparing the panels for portraiture (Borchert, 2021). Similar to many painters of his era, Seisenegger maintained stringent standards for the materials that he worked with.

Since their creation, these portraits have undergone some alterations and have been subject to several previous restoration interventions before being entrusted to the care of Sofia and Perrine here at the conservation studio.

The portraits were carefully studied upon arrival to establish a general overview of their condition and the previous restoration campaigns they had undergone. Through observations in natural light and UV reflectance, testing, and comparisons with other portraits by Seisenegger, it was determined that the original green and gold brocade of the background was concealed beneath a darkened accumulation of old varnishes, non-original glazes, and greenish overpaint. The overpainting might have been done with the intent of unifying uneven or overly cleaned paint. Another possibility is that the overpaint was an aesthetic choice following a trend. Similar examples of portraits from the same period with brightly coloured backgrounds hidden by non-original layers and overpaint can also be found.

Previous interventions, potentially dating back to the 19th century, were also identified in the panel structures. The planks were split, their joints planed down and subsequently rejoined with wooden half-lap insertions. This was likely done in an attempt to flatten the natural curvature of the wooden panels. The intervention is notably apparent in the portrait of the Archduchess, resulting in a loss of a few millimetres from the top to the bottom of the panel, extending vertically across the entire composition.

It was decided to focus the restoration of the panels primarily on the varnish and paint layers. A structural intervention aimed at correcting the discrepancy in the composition of the Archduchess’s portrait was deemed too risky. Following meticulous testing, the numerous layers of varnish, non-original glazes, and overpaint were gradually cleaned and softened using solvent gels, enabling their mechanical removal with scalpels. Though a time-consuming process, the results were rewarding as the beautiful hidden details finally emerged. Fortunately, aside from the edges, the original paint layer underneath was well-preserved, revealing a luxurious green-and-gold brocade.

Meet our art handlers

For this unique behind-the-scenes feature, we talk with the team of art handlers who work for The Phoebus Foundation. Get to know Idris Sevenans, Claire Dieltjes, Bram Van Broeckhoven, Claartje Borgmann and Florian Sevenans who manage and organize, under the supervision of our COO Luk Van Hove, the operational ins and outs of the artworks from our collection. The team not only ensures the safety of the works of art, but also of the people who come into contact with them. Every piece that enters the depot is carefully checked for potential contamination by micro-organisms and framing problems and then inventoried. This procedure is important for the further progress of the preservation and conservation of the artworks. Although every work is treated with precaution, efficient handling is a must.

The art handlers tell you more about the art of art handling:

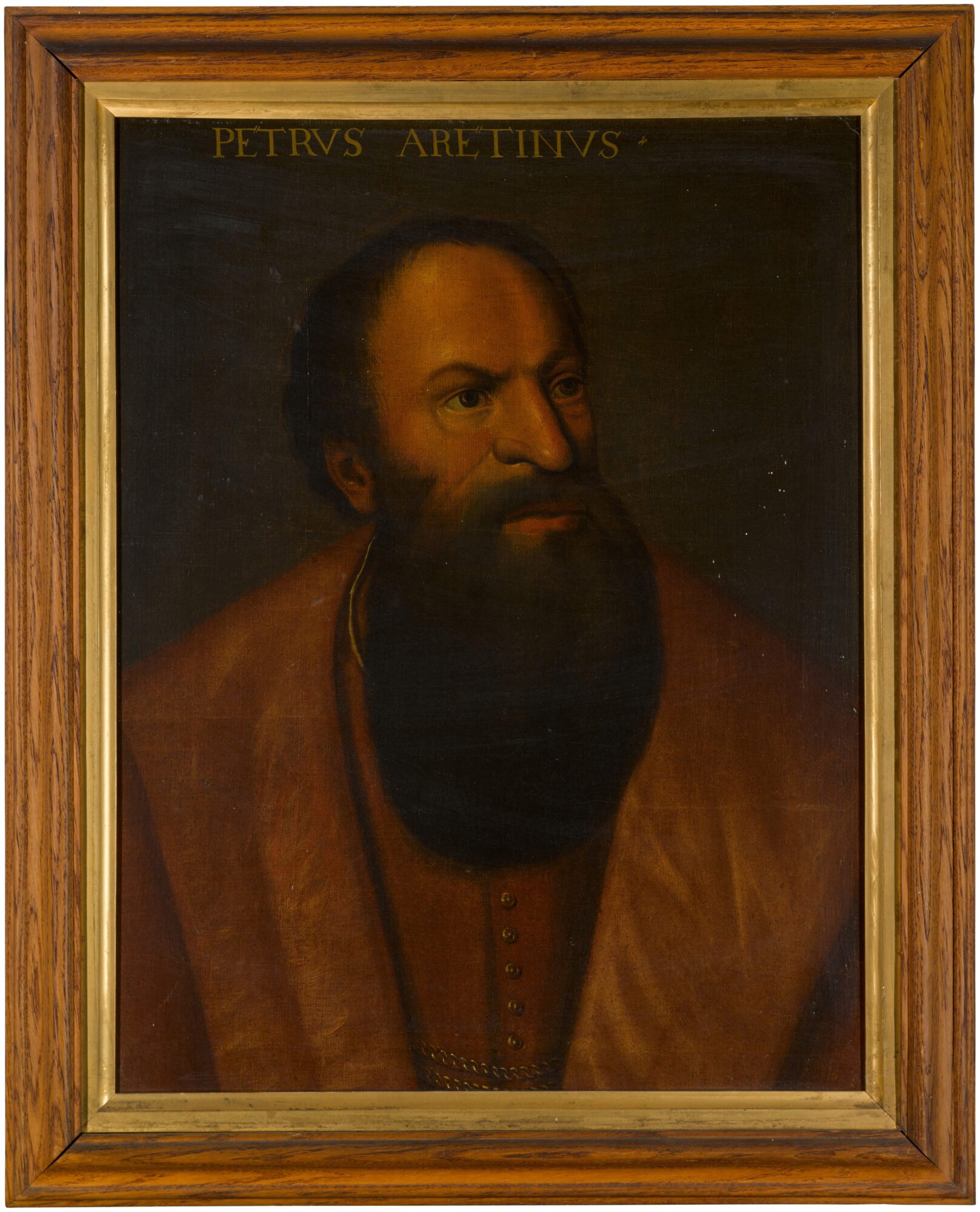

Florian: ‘Although my personal interest and passion are rooted in philosophy, I find the depot a particularly interesting working environment because I come into daily contact with very diverse works of art that are interesting from a historical perspective. Some artworks are not only aesthetically captivating, but are also sometimes a play on historical irony. Certain objects are literally and figuratively being brought closer together. In the depot, for instance, we hung a series of portraits of Italian writers side by side, including a portrait of Giovanni Pico Dela Mirandola (1463-1494). In 1486, this 15th-century nobleman and philosopher wrote an important treatise on the dignity of man in which he set out his views on truth and man’s place within the universe’.

Next to it hangs another historical figure from a later period, Pietro Aretino (1492-1556). In his writings, he highlights the less flattering elements of human existence in his writings, such as the abuses of the church and the tameness of ecclesiastical authority. His writings instilled fear in sixteenth-century high circles. He was considered one of the first art critics and had contacts with great artists. As a result, these two portraits, where a whole story could unfold, suddenly become incredibly interesting when placed in confrontation with each other. It is very pleasant to work in an environment that triggers an almost daily historical sensation and awareness. This creates a connection with the bigger picture and adds value to preserving and passing on artefacts.’

Bram: In the past, I often came into contact with art history due to my academic background but also because of my professional life as a historical art expert for art auctions. It never fails to fascinate me how the value of artworks is influenced by historical facts, and how knowledge of material and technique within the art world adds value to a work of art. For example, I recently came across Catharina Hemessen’s (c. 1527/1528-1567) Portrait of a Lady (1550) where it was thought that a tortoiseshell horn had been used. In collaboration with the conservation team, we were able to reveal that it was merely an imitation. Our expertise thus becomes an added value for the recognition and identification of artworks. Caring for them on a daily basis is truly rewarding!’

Art handler and artist Idris Sevenans also brings a strong dynamic to the team of our art handlers. Additionally, he is involved in analysing and dealing with art (archives) through his organisation AARS (Antwerp Artist Run School), providing a refreshing perspective on the goal of preserving and caring for art objects.

Idris: ‘During my research at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, I was confronted with the transience of art objects and the importance of collecting them. Taking care of The Phoebus Foundation’s collection is a hugely rewarding cross-fertilization for me as an archivist and a teacher at the AARS (Antwerp Artist Run School). I thoroughly enjoy dedicating myself every day to both disciplines.’

Among all the male violence, there are also two amazing female art handlers: Claire and Claartje.

Claire: ”It’s rather a coincidence that I became an art handler. After completing my studies in fashion design in South Africa, I started looking for the next challenge. On the advice of my grandmother, I then came to Belgium to embark on a new adventure, which then brought me here. Walking into the depot every day, I step into another world. Moreover, thanks to my Antwerp-rooted colleagues, I have learned a lot about the country and city I now call home and their rich culture and history. I like the flexibility and variety of my job, but also security and planning. This is why I take on the administration of our team. Good planning and communication are crucial to successful completing our responsibilities. The friendship within our team ensures that no task is too hard and we come to work every day with a smile.’

The art handling team, which is continuously expanding in collaboration with Katoen Natie Art, is currently preparing several large loan projects. The team actively participates in courses and tasks are divided based on experience and expertise. They are an indispensable part of The Phoebus Foundation family!

Conservation treatment of ‘The Party’ by Rafael Barradas

As part of the conservation of The Phoebus Foundation’s modern and contemporary Latin American collection, Rafael Barradas’s painting The Party from 1910 is currently in the hands of Clara Bondia.

It showcases an expressive figurative style that predates Barradas’ renowned vibrationism. Within the artwork, his skills as a caricaturist shine through, evident in the joyful expressions and celebratory atmosphere exuded by the characters.

The oil paint layers on the canvas exhibit a modified format, with noticeable clear edge truncations in several areas. It is possible that these alterations were made either over time or by the artist during the creation process.

Through a comprehensive comparative analysis and empirical research, it was determined that the work was formerly lined using a resin wax system. It is evident that the initial adhesion between the pictorial layer and the canvas was inadequate, likely prompting the decision to conduct the lining treatment in the past.

The tonality of the artwork was slightly darkened by a layer of dirt on the surface, and it had developed a yellowish hue caused by the oxidation of a thin layer of varnish. The white layers of the dresses of the female figures were by far the most affected. Additionally, there were issues related to polychromy, including discoloration and the presence of thick overpainting that encroached upon portions of the original paint layer.

Due to the weak condition of the artwork, it was decided to perform several treatments, prioritizing minimal interventions with absolute respect for the artist’s original intentions.

The restoration process began with a two-stage cleaning procedure aimed at eliminating surface dirt and removing the discolored, oxidized varnish and overpainting. This restoration effort successfully revitalized the work, revealing the vibrant original colors. In the next phase, the missing polychromy was addressed by conducting both volumetric and chromatic reintegration. Finally, a thin protective varnish layer was applied to safeguard the piece.

This conservation project is part of a larger initiative focused on preserving the Latin American art collection of The Phoebus Foundation. It is a pleasure to treat this painting along with several other gems and return it to its original glory.

The restoration of ‘Prometheus Bound’

Giovanna Tamà is an independent conservator specializing in Old Masters. Join us inside the The Phoebus Foundation restoration studio as she unveils her captivating work on various projects, including the restoration treatment of Prometheus Bound. Let’s take a look behind the layers of paint together!

“One of my projects is the restoration of a painting by the studio of Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), Prometheus Bound. A larger-scale depiction by Jordaens with the same subject and composition from around 1640 is currently in the collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne. It was common for Jordaens’ large and successful studio to produce reproductions of pre-existing compositions by the grand master.

Jordaens like to paint mythological and allegorical scenes, alongside genre scenes. In this particular artwork, he portrays the tale of Prometheus, who faced the wrath of Jupiter. His punishment involved the constant torment of having his liver pecked at by the supreme god’s eagle. This cruel fate befell Prometheus for daring to bring fire to men.

Over the years, the painting has already undergone some restoration treatments. It was given a new carrier and has been lined. In this old restoration, the edges of the canvas were cut off, so a small piece of the composition was lost.”

“The painting was not in the best condition. Over time, it had taken on a highly darkened and soiled appearance as the varnish had yellowed greatly. To hide wear and paint loss, large areas of the original paint were carelessly painted over in the past. Numerous unnecessary accentuations were also added to the bodies of Prometheus and Mercury (figure above right).”

“During the removal of the varnish, the old retouching and overpainting, the original colors were restored to their glory. The details came back to light, and we could finally see the painting technique. After cleaning, an isolating varnish was applied to create a barrier between the original paint layer and the restorer’s interventions.”

Currently, Giovanna is working on the final stage of treatment. The next step is to fill and retouch the gaps in order for the painting to receive a final varnish.

Restoration of ‘Theatrum Orbis Terrarum’

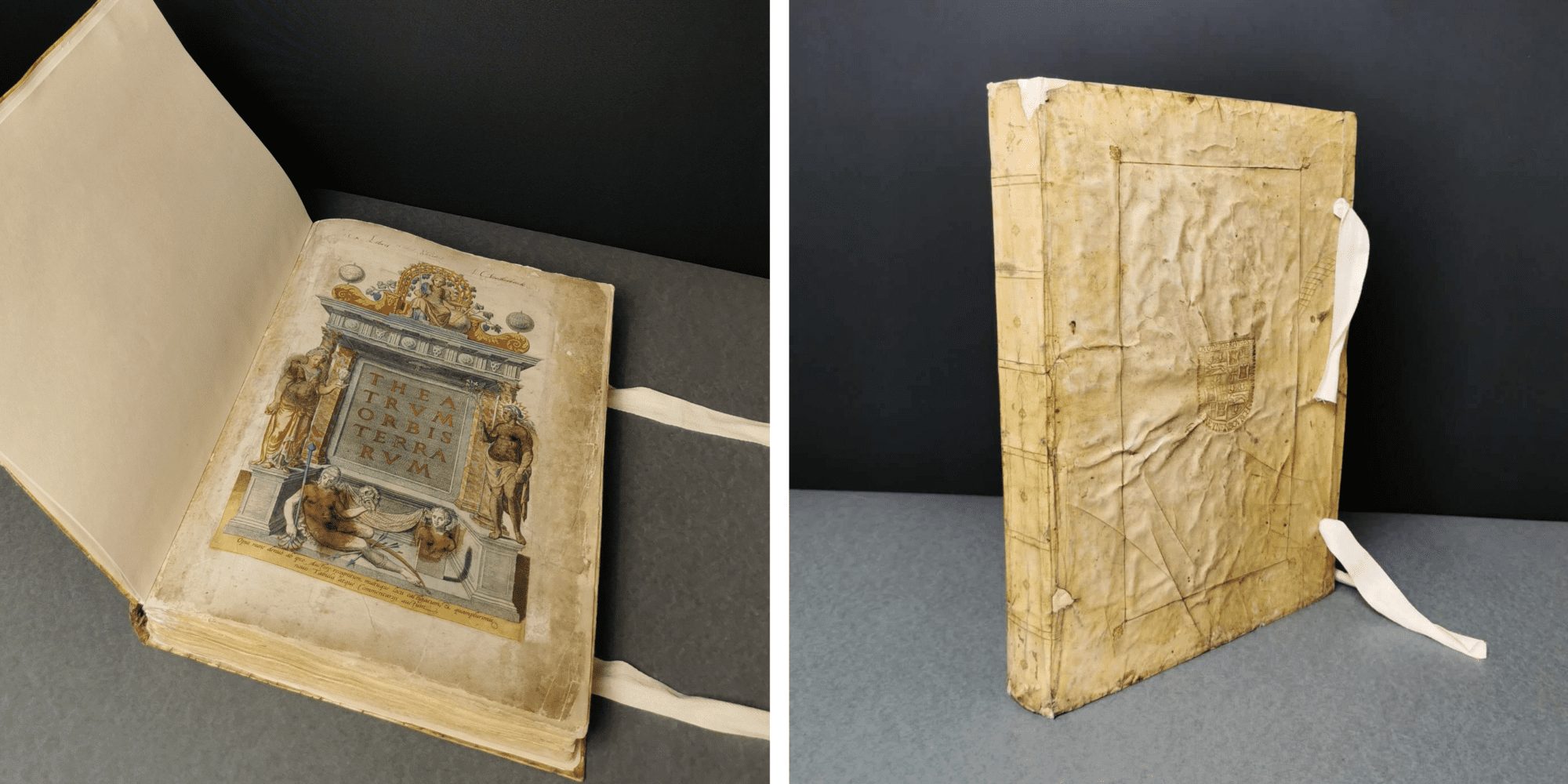

Oliver Claes has now been working as a paper and book conservator for more than a decade and is currently in charge of the conservation of the topographical and historical book collection from The Phoebus Foundation collection. For the last couple of months, Oliver’s work included the restoration of Abraham Ortelius’ sixteenth-century masterpiece Theatrum Orbis Terrarum.

“The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (‘theatre of the world’) is the very first world atlas, published on the 20th of May 1570. The volume was created by the Antwerp-native Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) and published by Gillis Coppens I. Ortelius compiled the best and most reliable maps of his time into one volume. A unique feature of it is that all the maps were engraved in the same style and size on copper plates, and were arranged by continent, region and state. This ensured that the atlas remained popular for decades and was even translated into other languages.”

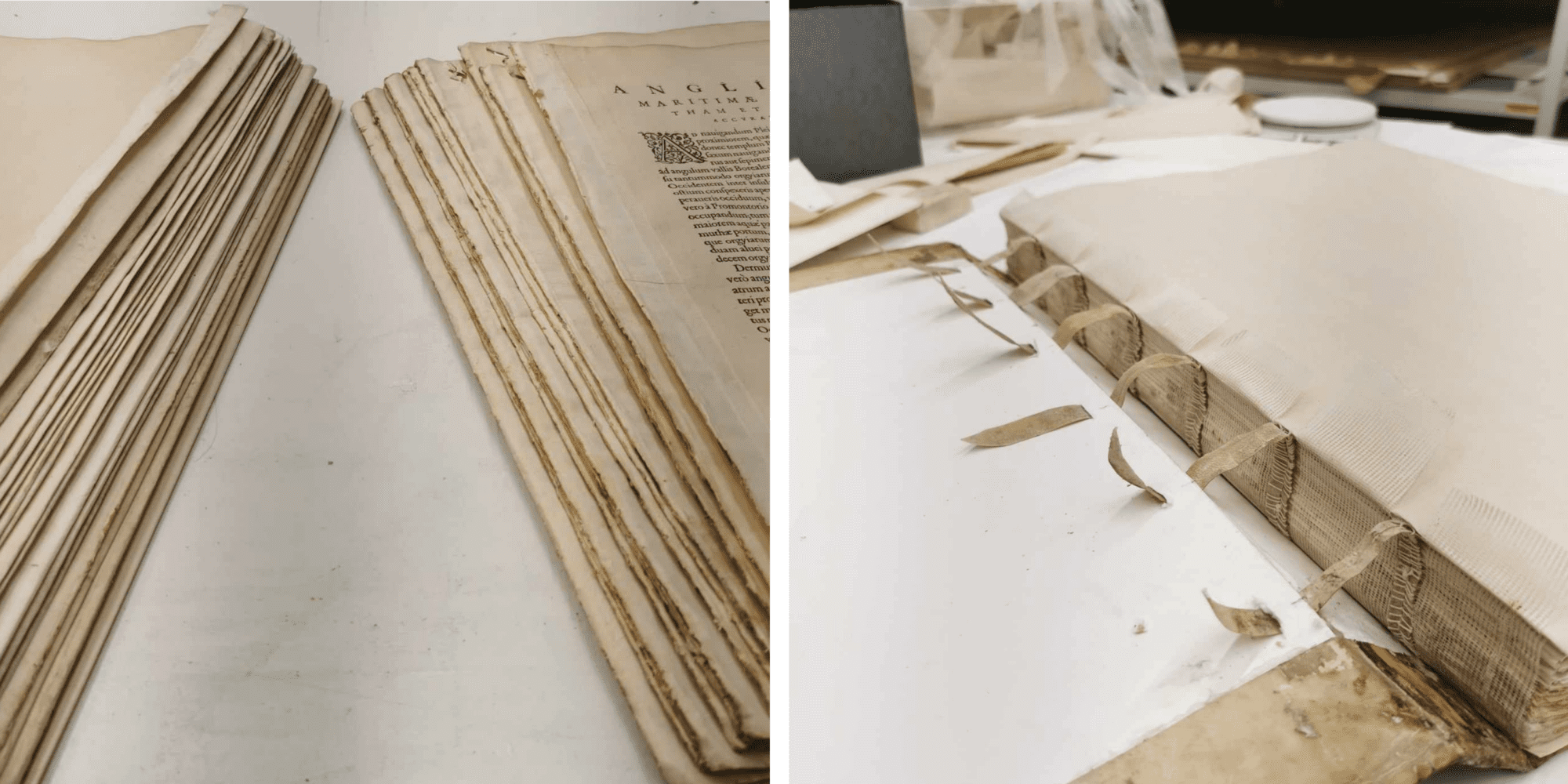

“The condition of the book was very poor. The book block (the collection of quires) was very soiled, and the binding distorted. Moreover, it had also come loose, and the various quires revealed multiple damages and gaps. The binding made of parchment was broken and could no longer fulfil its role of protecting the book block. Furthermore, the sturdiness that a binding should provide to the book block had completely disappeared due to the lack of sturdy cartons. Upon opening the book, the fragile and coloured title page immediately became visible.”

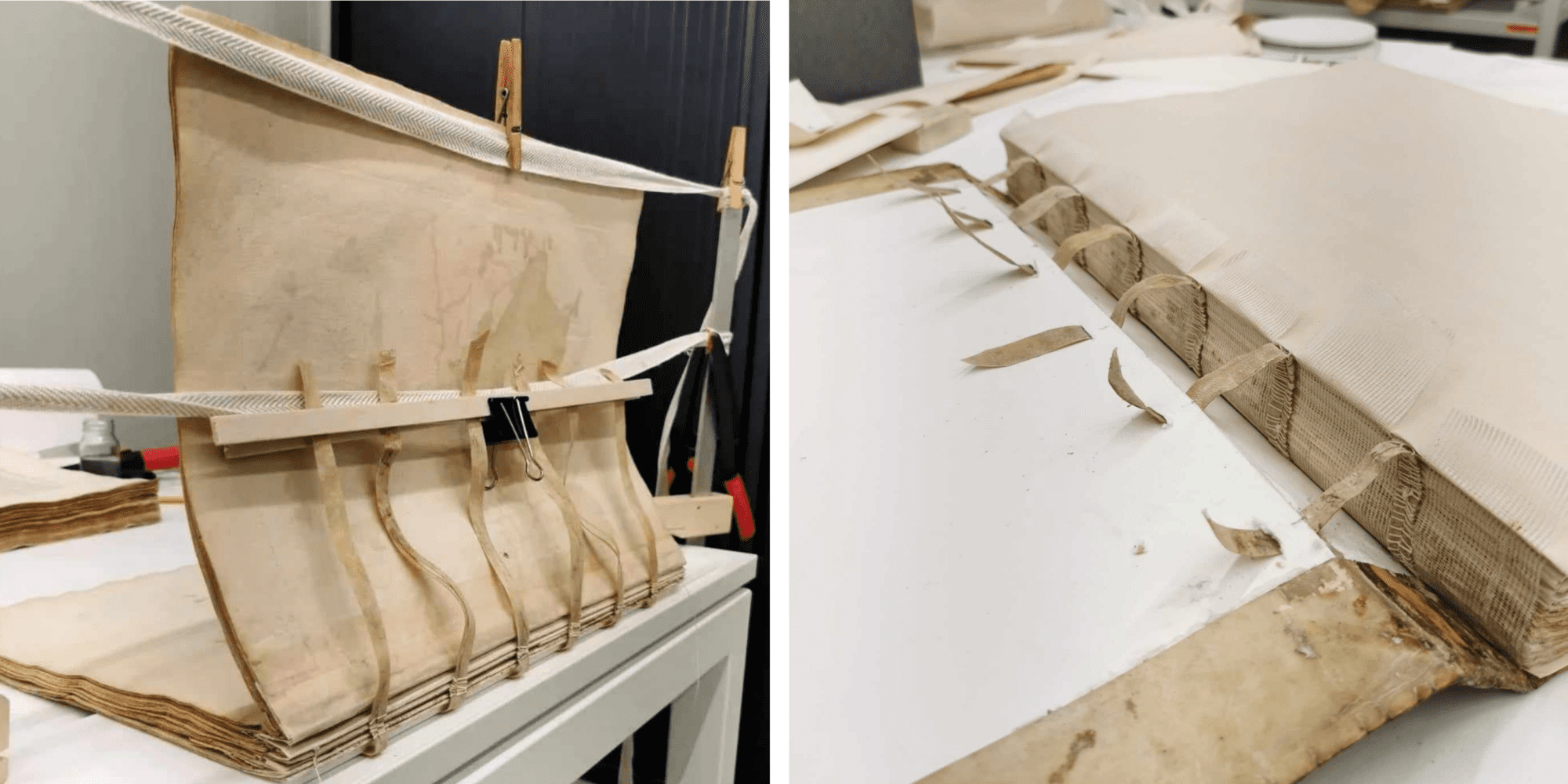

“The outline of the restoration was a thorough cleaning of all parts, filling in and reinforcing the book’s binding and strengthening it. For this, the book had to be completely dismantled. All the quires were reinforced piece by piece with Japanese or Western paper (and starch glue).”

“Afterwards, all the quires were similarly bound with twine on parchment strips. The title page was also cleaned, completed and retouched. A fun finding during the restoration of this book was that a drawn “little man” was discovered on the inside of the parchment folded over the cardboard (of the book binding). Presumably, this was a personal addition by the bookbinder.”

“The vellum of the book binding was repaired with similar vellum and the lost cartons (covers) were filled in with acid-free cardboard.”

“A big problem was also the lack of endpapers. These are needed as protective pages at the front and back of the book. After a fruitless search in various art and paper shops, I finally had the paper artfully made by the Walloon master papermaker, Pascal Jeanjean. Based on a sample of the original paper (part of a flyleaf at the back of the book), he produced a similar paper for these books which, like the original sheets, are also handmade. Handmade paper can be recognised by the water lines or watermarks you see when you hold the paper up to the light.”

Pascal explained more about this himself:

“I’m going to try to give you an idea of how I made the paper. Because it was for the restoration of an old book, I chose to use raw materials similar to the original of the atlas’ paper, namely cotton rags and cloth. After treating the cotton rags in a bath, I started loosening the cotton into pulp in a Valley Beater, a modern version of a “Hollander”. This pulp thus forms the basis for the later paper. To create the right paper colour, mineral powders were added to the pulp. Calcium carbonate was added to increase its alkaline reserve.”

“After the right pulp was manufactured, a scoop window was chosen with a similar pattern of thin copper wires as in the original paper sample. Then, from a large bin, the paper was scooped. Subsequently, a pile of paper with felt interlayers was stacked on top of each other. Then, a large paper press was used to remove most of the water from the paper (60%). With intermediate sheets of special cardboard, the remaining moisture was removed from the sheets.”

“The straps on which the book was joined were glued through and onto the cartons of the book binding during the rejoining of the binding and book block. This ensures that both parts stay tightly together. The new endpapers were glued to the inside of the boards (plates) of the book binding. Finally, new ribbons were added to the book binding.”

‘Noli me tangere’

In July, we welcomed a new Phoebus Fellow into our conservation studio: the French-Dutch painting restorer Annika Roy. For the next three months, Annika is taking care of Hendrick De Clerck’s Noli me tangere.

“This painting, dated between 1560 and 1630, depicts a famous passage from the New Testament, Noli me tangere (“Do not touch me”). It reads a little bit like a graphic novel. The first scene on the foreground shows Maria Magdalena, encountering Christ, after his resurrection. Mistaking him first for a gardener because of the shovel he is holding, she recognizes him, and Christ speaks the famous words ‘Noli me tangere’. You will also notice a second scene in this painting. On the right side, you can recognize the three holy women at Christ’s tomb and Maria Magdalena among them. They find the tomb empty, and an angel announces Christ’s resurrection. Your gaze is then guided to the Golgotha hill in the centre of the painting and in the background, you can see the city of Jerusalem.”

“Even before the treatment, it was clear that the painting has very bright colours and that the paint layer is in good aesthetical condition. The paint is rich in oil, and the glazes used by Hendrick De Clerck in the red and purple drapery of Christ and Maria Magdalena for example, are well preserved. It is very satisfying to notice this painting was not overcleaned in the past. De Clerck’s burshstrokes are very visible in the brown colours, where we can see the preparation in transparency. Furthermore, smalt pigment (blue coloured glass) has likely been used for the blue parts of the painting (sky and some draperies). The pigment unfortunately discoloured a little with time.”

“The oak panel, consisting of four horizontal planks, underwent some structural treatment after which I could focus on the paint layer. The main damage was the up-lifting paint around the fills near the joints of the panel. The other alterations were mainly aesthetical: the fills were uneven, and the retouches were visible, especially the ones containing white. The varnish was also slightly yellowed.”

“The first treatment consisted in fixing the paint around the joints. I could then start the cleaning process, consisting mainly of the removal of the former restoration material: varnish, old retouches and fills around the joints. Some fills were overlapping on the paint layer. By removing them, it was exciting to uncover hidden original paint.”

“In the upcoming weeks, the losses around the joints will be filled again, the painting varnished and then I will be able to start the retouching phase. It is a real pleasure to work on such beautiful panel and appreciate every detail of it.”

Curious about the results? Keep an eye on our website and social media!

Discover the unique portraits of the Inca emperors and Francisco Pizarro

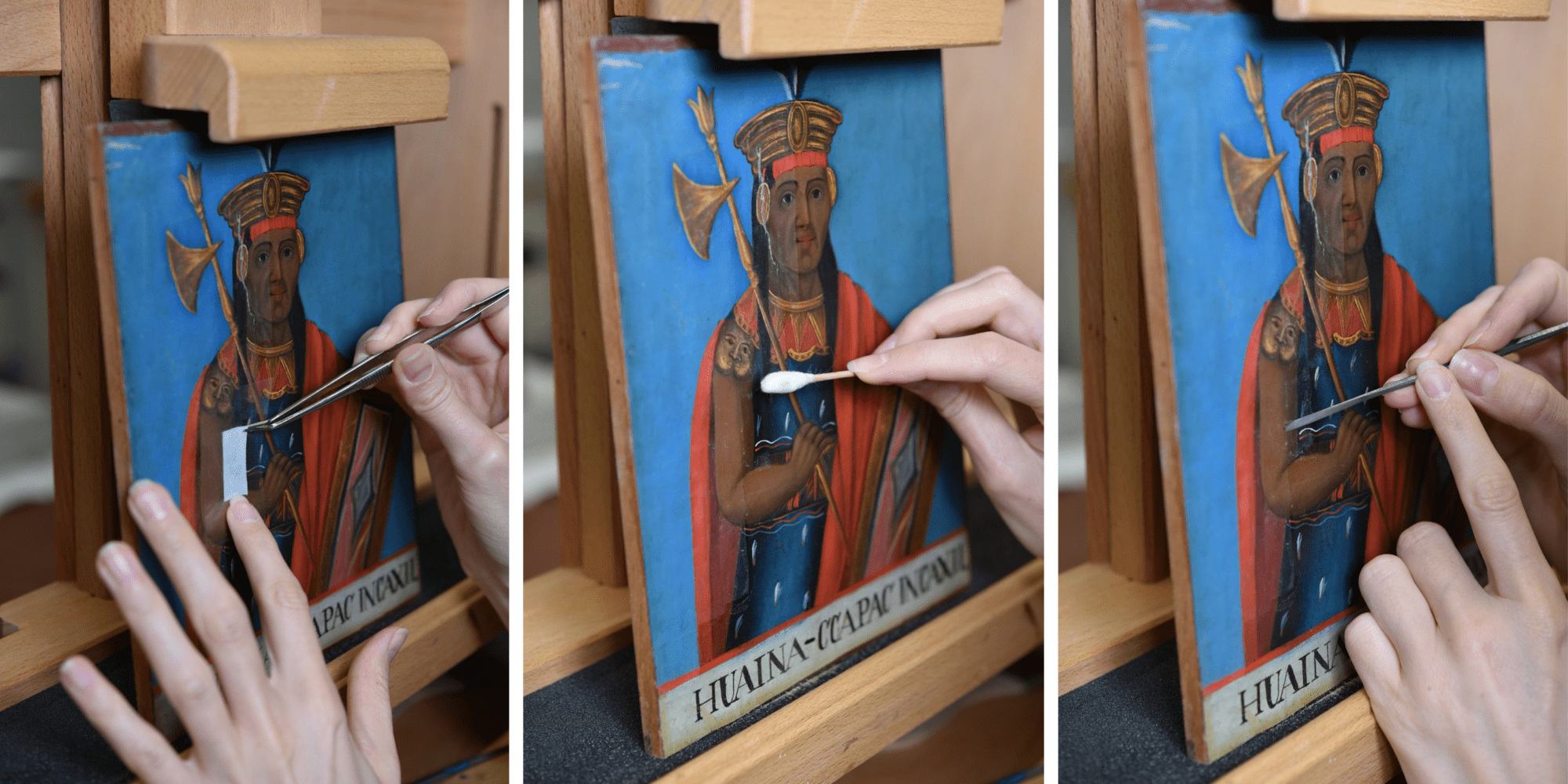

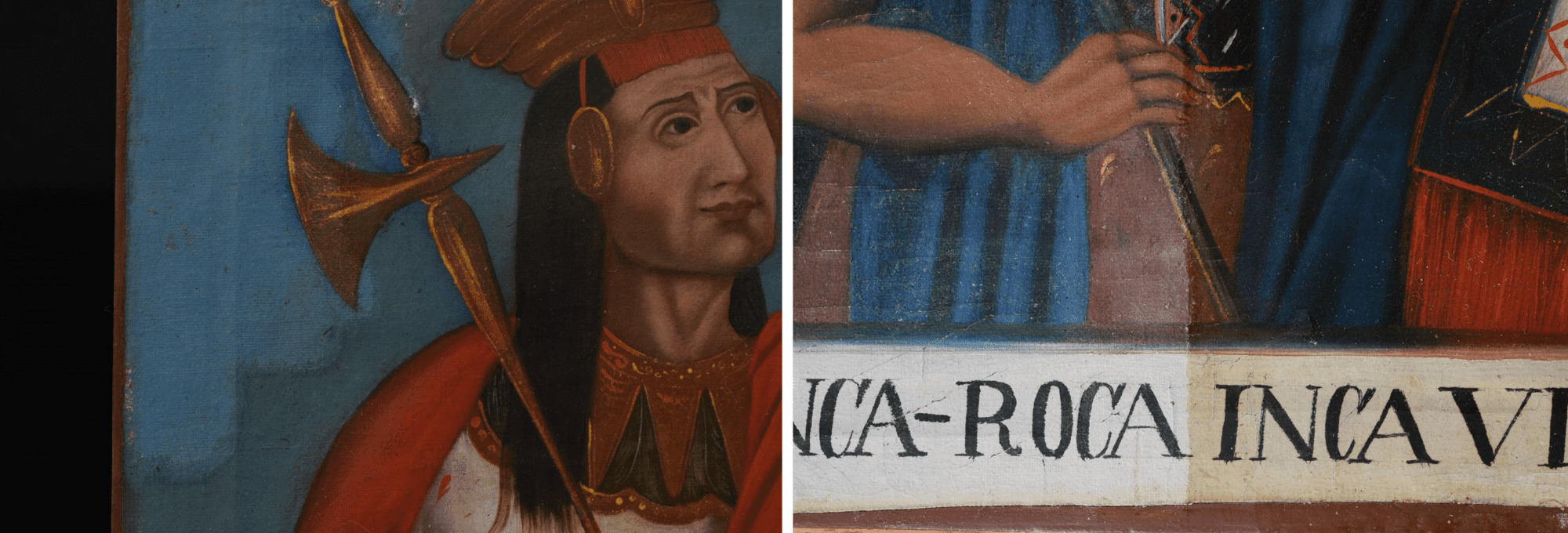

At The Phoebus Foundation’s restoration studio, conservator Carlos González Juste and former Phoebus Fellow, Kaisa-Piia Pedajas, are currently restoring a unique series from the Phoebus collection, namely twelve portraits of Inca emperors and Francisco Pizarro. This month, we dive behind the scenes and take a closer look at this fascinating project.

Anonymous, Portraits of Inca Emperors and Francisco Pizzaro, c.1790-1810

These portraits, each no larger than an A4, depict an idealised representation of the Inca emperors and the figure of Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of the Inca Empire. Portrait series such as these were very popular in the Viceroyalty of Peru during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Moreover, they were eagerly used as political tools. The iconography is based on an engraving by priest Alonso de la Cueva (1684-1754), in which the genealogy of the Inca emperors is succeeded by the Spanish monarchs. In this way, the Spanish rulers strengthened their claim as heirs of the Inca empire.

Throughout time, this message took on other meanings. The iconography was also used to document and confirm aristocratic Inca blood in certain families. As a result, family members linked themselves to Spanish nobility and were entitled to special privileges, including exemptions from taxes. As feelings of independence grew throughout the Viceroyalty, links with the Spanish monarchs were removed as an effort to restore the Inca empire.

Complex carrier and damage

Time to take a closer look at the portrait series. Studying the stretchers, it is clear that the portraits were produced on canvases, presumably made of cotton, and glued to strainers. However, this was not their original display. The irregular profiles reveal that the canvases were once cut from their original stretcher frame and then glued onto a new strainer. The canvases themselves are extremely thin with flat, regular waves, suggesting they were machine-made.

Beneath the blue background, we see a reddish ground, which is visible thanks to the transparency of the paint layers. These are so thin that it is almost impossible to see brush strokes!

Before the paintings came to the restoration studio for treatment, they had a dark, yellowish varnish layer and several overpaintings covering the canvases’ damages and edges. This varnish layer and retouches were also very irregular. The supports themselves were also particularly distorted due to the gluing to the strainer, creating strong tensions between the glued edges and the canvases.

Behind the paint layers

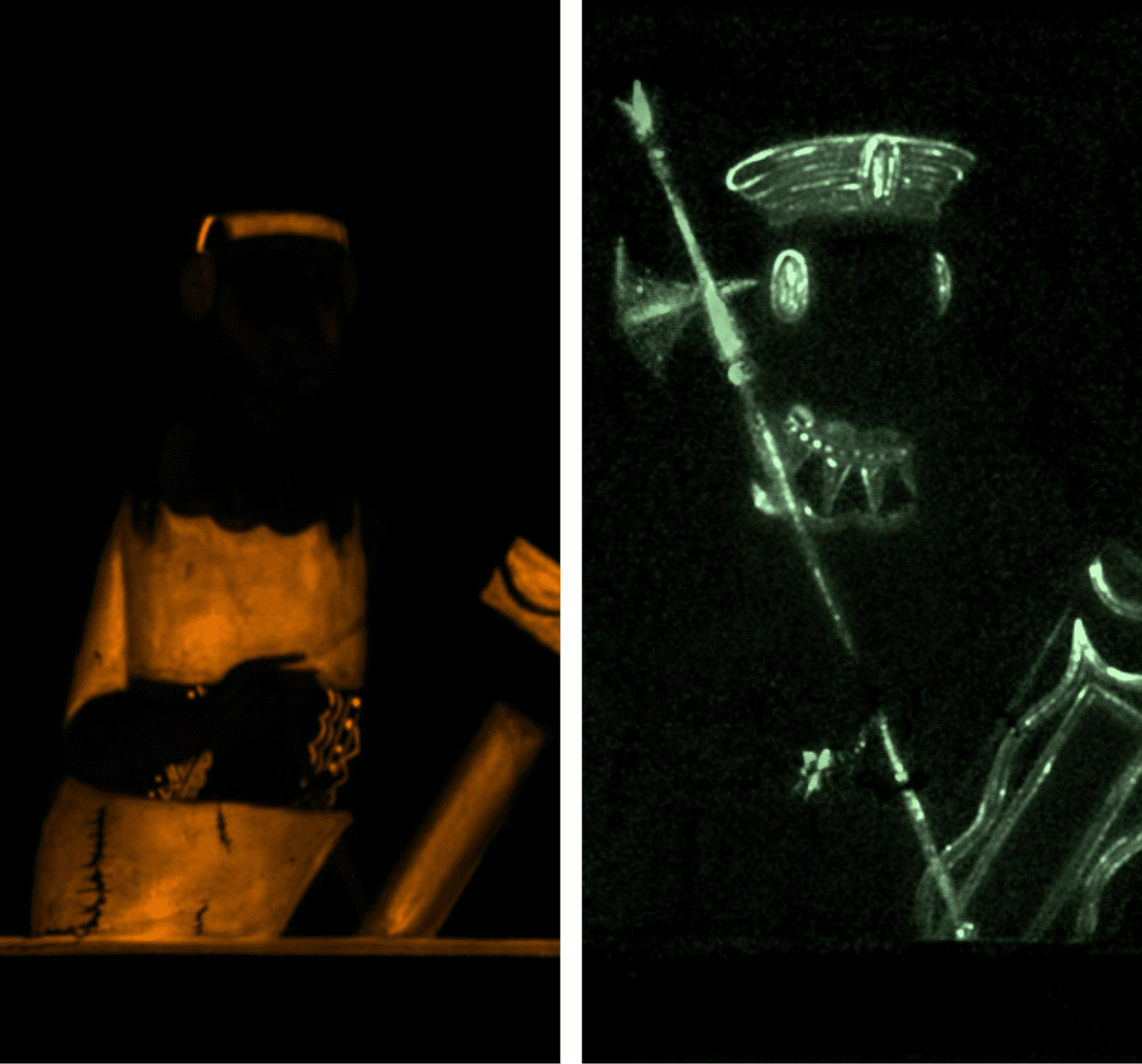

To find out how the portraits were created, we analysed one of the paintings using the imaging technique Ma-XRF. This scientific technique allows us to distinguish the different chemical elements of the painting and thus identify the pigments that make up the work. The resulting research showed the use of pigments from the last decades of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, confirming the possible execution date. Among other things, the Ma-XRF images showed us the presence of mercury, indicating the use of vermilion for the colour red, while arsenic points towards orpiment for the gold areas.

Before starting the restoration treatment, thorough tests were first carried out to find out the best method to remove the varnish. This was because it had darkened and had not only changed the colours of the paint but also made the supports, and the cloths, enormously stiff, resulting in various deformations. For cleaning, we opted for a non-woven Evolon® fabric and solvent mixtures that swell the varnish layers and can thus be easily removed with a cotton swab. In some areas, we also combined these techniques with gentle mechanical cleaning.

Certain pigments showed greater sensitivity and required extra attention. Additionally, we noted that the paintings had been only partially cleaned during previous restoration treatments and that a darker layer remained in some places (such as the incarnate and accessories of the portraits). After taking off the varnish layers, we also removed several overpaintings from the surface and reduced stains where necessary. Although the paintings initially looked the same, it became clear during and after the cleaning that the conditions of the paint layers and supports were vastly different for each portrait.

Thanks to the removal of the rigid layer on the paintings, the canvases also became looser and distortions reduced significantly in most cases. Many paintings were placed under weights to make the canvas slightly flatter. Areas and distortions that required extra effort were carefully treated with moisture and underwent thermo-treatment.

Furthermore, we also repaired the tears that were present in the canvas of some portraits. To minimise the damage, these tears were flattened and the edges were also aligned. They were then consolidated and supported on the back with a suitable adhesive.

After the structural treatment, a thin layer of natural varnish was applied. This layer acts as an insulation layer for the original surface and helps to saturate the colours after removing the old varnish layers.

The restoration of this exceptional portraits series is still in full swing! After varnishing, our conservators will also continue to fill and retouch the gaps. As a result, the Inca emperors and Francisco Pizarro can soon be admired again in all their glory!

Curious about the results? Keep an eye on our social media and website!

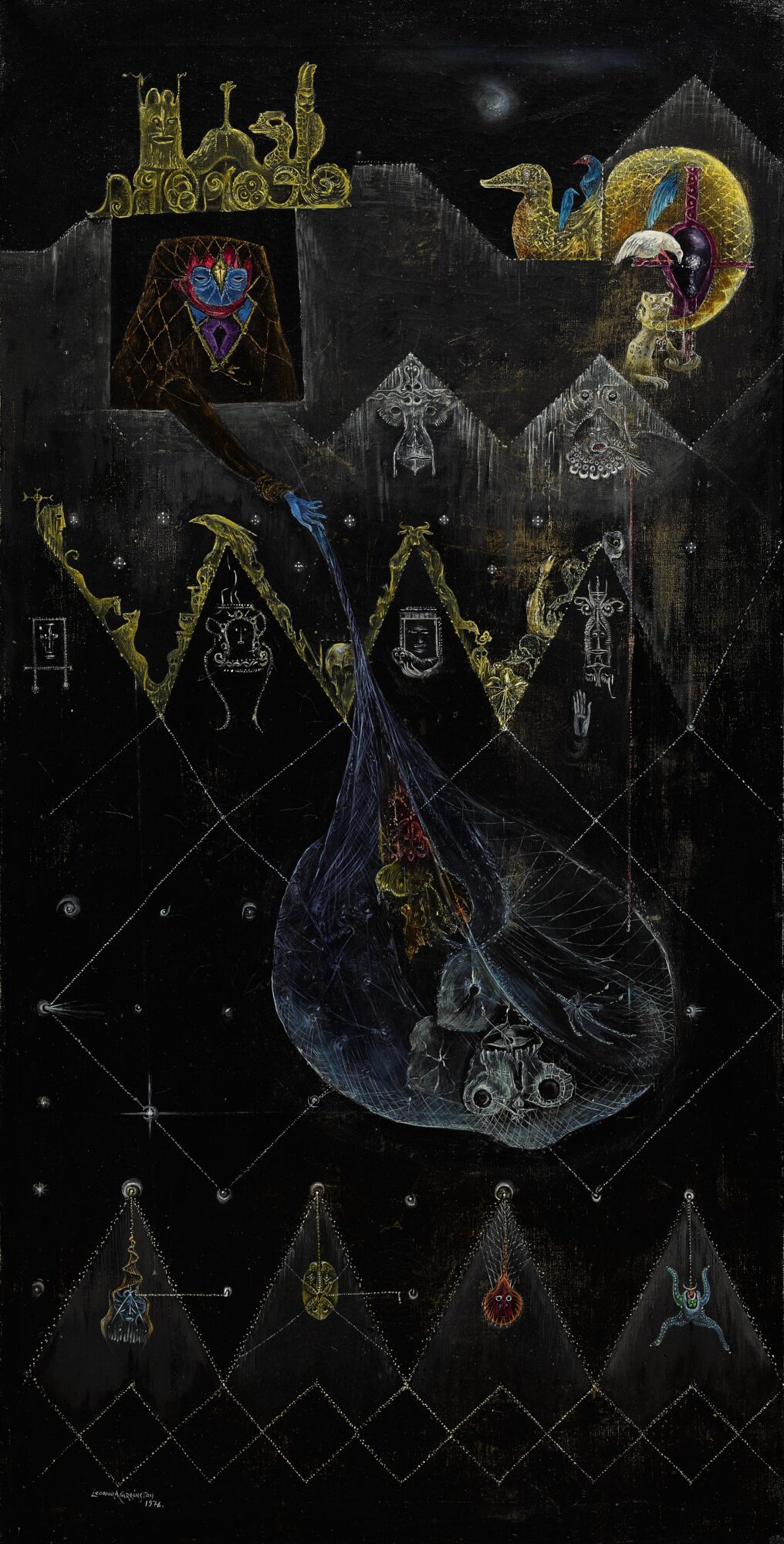

Take a step into the wonderful world of Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington’s work, The Dark Night of Aranoë is part of the Latin American sub-collection of The Phoebus Foundation. Restorer Naomi Meulemans is in charge of the foundation’s modern and contemporary collections and started the restoration of this work following a future loan project. This month, she takes us behind the scenes of the research, the restoration and the wonderful world of Leonora Carrington.

“Leonora Carrington’s work seems to lean close to her own life. It is fragile, almost velvety at times, but also dark and analytical. Although she often painted for an unfamiliar audience, it seems as if, for a moment, we may look deep into her hidden dreams, deep happiness and at the same time, raw trauma. All these symbolic figures and sophisticated elements are also present in The Dark Night of Aranoë. Usually, only the figures or decorative elements were thickened in the paint. This way of working creates space and quickly takes the viewer far away from our “recognisable” world because of the absence of any kind of technical perspective.”

Details of The Dark Night of Aranoë

“A major comparison study with some of Carrington’s other works and a study of her methods lead us to suspect that the work was varnished at a later date, long after the work was created. Indeed, Carrington’s paintings are always very matte or even unvarnished. Because of the damage the layer does to the work, it was decided to remove it during the conservation campaign. With the restoration, we hope that this captivating work will find its strength again to inspire the viewer.”

Behind the scenes with Jill and Ellen Keppens

This month, we go behind the scenes with twin sisters Jill and Ellen Keppens, who are currently restoring the seventeenth-century portrait of a nobleman from the Volpi family with his wife and children.

“A while ago, we were introduced to the Volpi family. This intriguing family of important diamond merchants, some with Italian roots, was active in 17th-century Antwerp. The fact that they were good at doing business is amply demonstrated in this portrait, through the depiction of white silk, pearls, diamond jewellery, lace, feathers, impressive buttons, a horse, a greyhound, their coats of arms and even the imposing footwear.”

“Besides all this opulence, something else extraordinary catches the eye. The extremely pale incarnations of the woman in the white silk dress and the two children immediately catch the eye. Why their skin is so white is still a mystery. Has the pigment become discoloured and transparent? Does the white skin show their privileged position? Or were they already deceased when this portrait was painted? More research on the family may provide an answer here.”

“The white incarnate is not the only ‘strange colour’ that stands out. The clouds also look bizarre. This is because the sky around it is discoloured. At one time, it must have had a strong blue colour, but the artist used smalt as a pigment. 17th-century artists often used this pigment containing cobalt because it was cheaper than the expensive ultramarine, yet could still obtain a nice blue colour. Unfortunately, it is also very unstable and over time, it often turns brown, yellow, grey, or becomes transparent.”

Curious about the final result? Keep an eye on our social media and website!

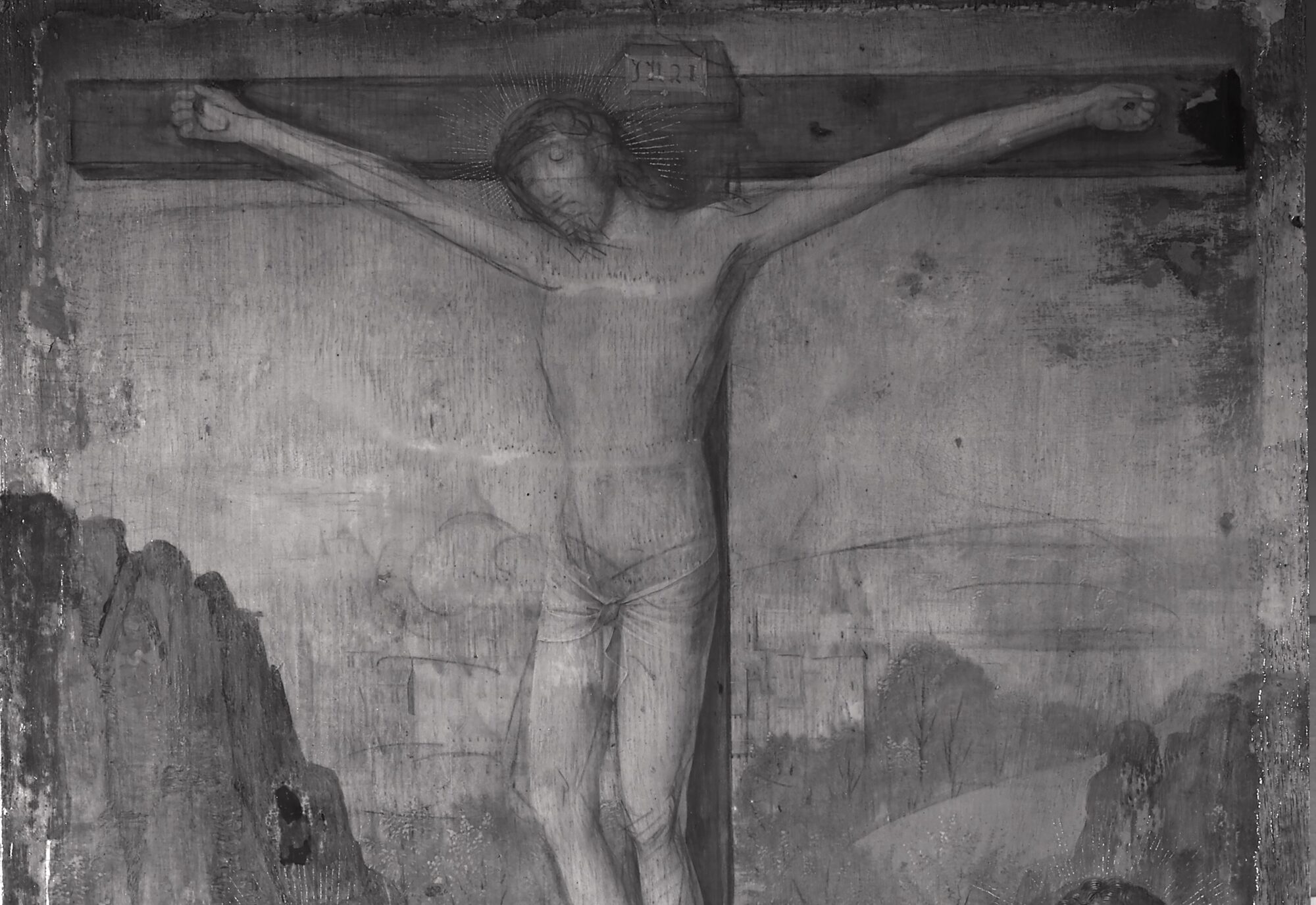

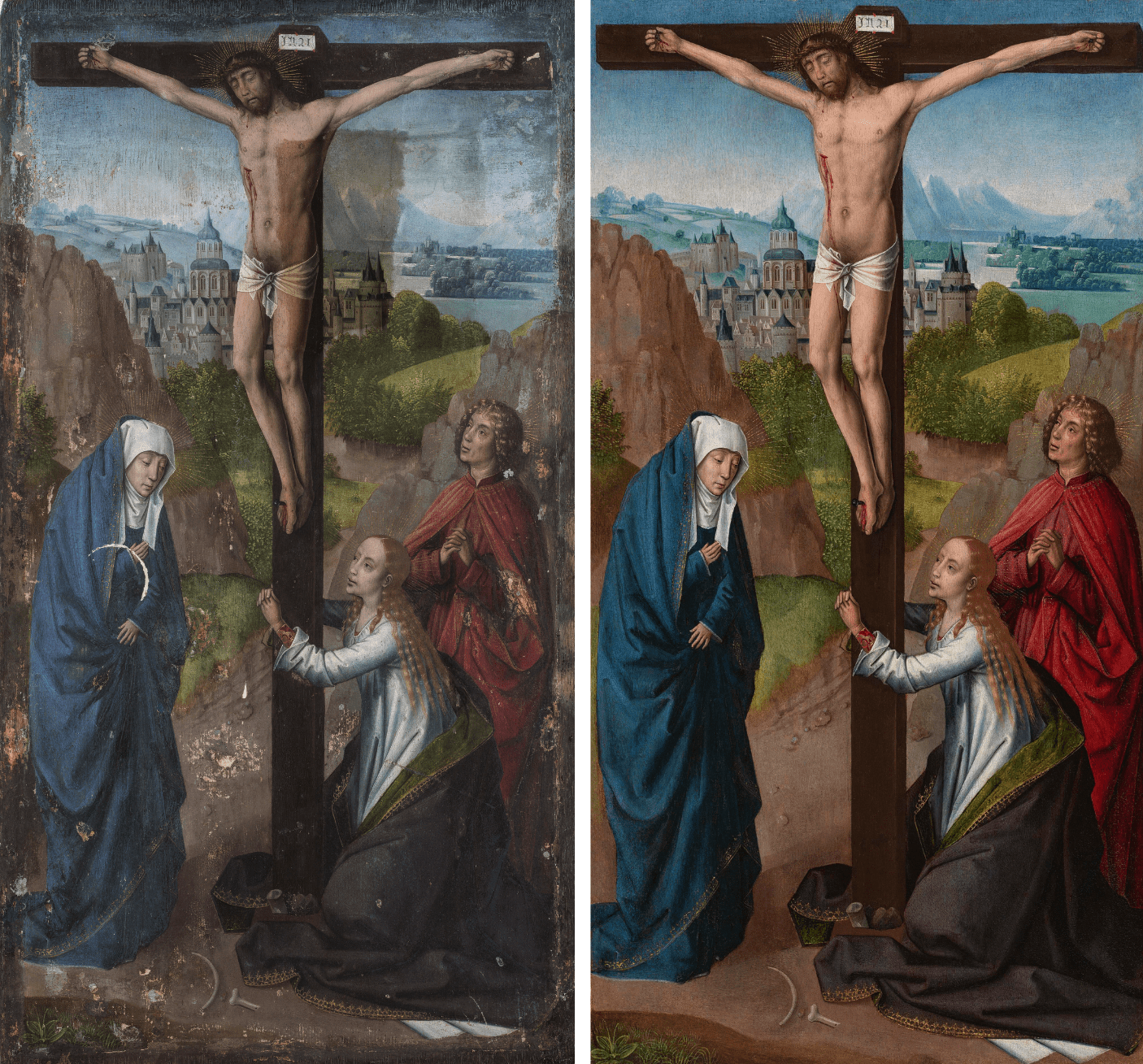

Conservation treatment of The Crucifixion panel by Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy

This month, Chief Conservator of The Phoebus Foundation Sven Van Dorst tells us about the conservation treatment of The Crucifixion panel by Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy. He masterfully describes how this work was created, where the stylistic influences come from, and what the damage phenomena can teach us. The power of this restoration emerges when we get closer to the heart of it through research techniques Sven employs in the process.

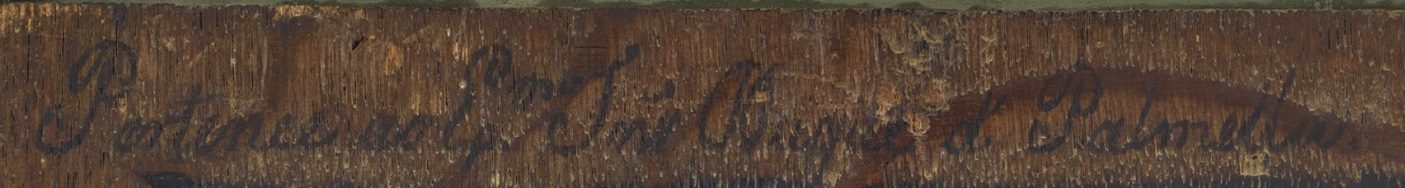

Before restoration

“This small panel depicting the crucifixion was painted by the Master of the Lucia Legend. His work is close to that of Hans Memling, so it is assumed that he was active in Bruges at the end of the 15th century. Based on an inscription on the back of the panel, we discovered that the little work ended up in Portugal during the 19th century in the collection of the Dukes of Palmella.”

“Before the restoration began, the painting looked dull. The colors had a greenish appearance because the varnish was heavily discolored. With the help of Infrared Reflectography (IRR) and radiography (X-ray), it was possible to evaluate the condition of the painting in detail. As a result, we found out that the edges of the painting were completely overpainted. Originally, there was a border of about 1cm of unpainted wood around the work. This is typical of 15th-century paintings because the wooden panel was held in the frame using a groove. On the IRR, we can see some minor damage in the paint layer and the underdrawing that the painter used to draw his composition on the panel. The lines are angular, indicating the use of a “dry” drawing medium such as chalk.”

“After the examination, the restoration could finally begin. It took some work to remove the old layers of varnish. Using homemade gels, the varnish could be swollen in several stages and removed from the paint surface with a cotton swab. Immediately, the original vibrant colors and some of the old damage reappeared. In the next stage, the old overpaintings at the edges were removed. This was done under the microscope to avoid damaging the underlying paint.”

“Once the original surface was exposed again, the final phase of treatment could begin. First, a varnish was applied to protect the original. Next, gaps were filled and retouched to no longer stand out. The result was stunning and one of my most enjoyable projects. Now it is again possible to appreciate the refined technique and palette of the mysterious Master of the Lucia Legend.”

Behind the paint layers with Sofia Hennen

This month, we take you behind the scenes with Sofia Hennen, paintings conservator and art historian, who recently restored the work titled Tavern Interior by Pieter Pietersz from our collection.

“The conservation-restoration treatment of Tavern Interior by Pieter Pietersz, dated from the second half of the sixteenth century, was trusted to me in May last year as my first project with The Phoebus Foundation. This beautiful oil painting on canvas immediately impressed me with its refined artistic technique. However, its condition also instantly startled me.”

“From the beginning, I noticed the painting was full of problems. Only after removing the varnish and overpainting did the real image emerge. The oxidized varnish and the altered past retouching concealed an excessively worn original paint layer that had endured harsh incidents over the past five centuries. Inadequate conservation conditions and past inappropriate restoration treatments, such as aggressive cleanings, invasive linings, old overpainting, etc., are some of the interventions worth mentioning.”

“Thus, the retouching of the painting after the cleaning was quite tricky and needed progressive and critical decision-making processes. As the painting showed generalized abrasion, it was necessary to bring retouching solutions that could conceal the damages in an “illusionist way” while respecting its material history. In other words, I had to subtly reintegrate the damaged image by imitating at the same time the abrasion and maintain this approach constantly. Keeping a homogenous and coherent aspect with the same quality of retouching all over the composition was difficult. Deciding when to stop was also challenging, as you could easily overdo it and keep retouching forever.”

“To conclude, this has been one of the most challenging treatments I have ever done, so I can only be proud of the result. I am already excited for future Phoebus challenges like this one!”

After restoration

Restoration of a Wim Delvoye display cabinet

This month, we take you behind the scenes with Brian Richardson, a specialist in the conservation and restoration of wooden objects and furniture. Brian recently worked on an unusual installation by contemporary Flemish artist Wim Delvoye, which consists of a display case containing 12 saw blades and a gas bottle, each piece painted in Delft blue. This finely crafted antique cabinet references the Flemish neo-styles with their richly carved auburn wood and glossy varnish.

Wim Delvoye, Installation of 12 Saw Blades and 1 Gascan

“The antique “look” of the cabinet does not immediately suggest how it is constructed. In fact, the entire structure is dismountable. The walls, base, and crowning are not fixed with wooden joints but are held together with a few bolts, making the whole thing rather unstable. The additional problem is that the glass door at the front is different from the usual format for such a cabinet. An antique display case would usually have two doors that open from the center with several small panes of glass. When this door is opened, it drops down. With the cabinet also dangerously lifting forward, there is a real chance it could topple forward.”

“The removable aspect of the artwork did make its restoration easier. The furniture was completely taken apart in order for me to work on the structure. After much thought and consultation, the approach was outlined. At the bottom of the side walls, four new wooden joints were provided to connect the walls to the base. This invisible intervention significantly improves the stability of the cabinet and counteracts toppling. Lastly, four L-shaped brackets were installed on the back of the furniture.”

“In addition to these major structural interventions, smaller treatments such as gluing cracks, filling gaps in the wood, and retouching old impact damage were also performed.”

“Due to its complexity, restoring this antique/contemporary display case presented an enormous challenge, but the result was all the more satisfying.”

Behind the scenes in Sudbury

Collection Consultant Katrijn Van Bragt and Conservator Naomi Meulemans take you along on their journey to Sudbury, Suffolk (UK), for the installation of the Painting Flanders exhibition at Gainsborough’s House!

The works of art arrived safe and sound in Sudbury

Katrijn and Naomi made sure more than 40 masterpieces by Emile Claus, Gustave Van de Woestyne, James Ensor, Rik Wouters, and other Latem School artists could travel safely to Sudbury. Not an easy task in Brexit times! Each artwork was extensively analysed before departure and was packed in a custom-made crate. Aside from that, all customs formalities were arranged so the artworks could travel to the UK.

After crossing the channel and arriving in Sudbury, the paintings and sculptures were thoroughly checked to see if any damages would have occurred during transport. After everything was all cleared, a specialized team of art handlers installed each artwork under the critical eye of Naomi and Katrijn. Then, after applying labels and introductory texts to accompany the exhibition, testing the audio guide, and adjusting the lights, the exhibition was finally ready to be shown to the world!

With Painting Flanders, The Phoebus Foundation presents the story of an essential piece of Flemish art history from the end of the 19th century to the UK. The exhibition is a real debut as it is the very first at the newly built museum, Thomas Gainsborough’s House, in Sudbury, Suffolk. Discover the unique show until the 26th of February!

Phoebus Fellow of the month: Clara Bondia

This month, we take you behind the scenes of our conservation studio, where a new Phoebus Fellow joined the team for three months: Clara Bondia! Clara tells you more about her projects at The Phoebus Foundation:

“On the one hand, I am studying and working on an 18th-century Latin-American sculpture of The Immaculate Conception catalogued as Quito School, one of the most prestigious names in colonial imagery. The technique is gilded, stewed, and polychromed wood, and the carving and decorations are of the highest quality”.

“After the preliminary and analytical study using X-ray photography, I began stabilising the pictorial layer. The piece had been previously restored, so it was interesting to find out which parts were adhered to or overpainted. In this way, the degree of intervention could be determined. Once the pictorial layer was stable, selective cleaning was carried out, and some of the disturbing overpaint that distorted the view of the piece was removed. When the restoration is finished, it will allow for a better aesthetic reading of the piece.”

“On the other hand, I am also collaborating on an interesting research project on the work Muñecos (Dolls) by the Italian-Argentine artist Líbero Badii, which is an installation of several polychrome wood sculptures with oil. According to the artist, they represent “the figure of the massified contemporary man, and his need for vital cosmic projection, materialised through the strings that unite all the figures”. I enjoy working with contemporary art because of the great challenge it presents in confronting new techniques and new materials.”

“During my stay at The Phoebus Foundation, I will also be able to collaborate in the revision of some other works in the Latin American collection of modern and contemporary art, carrying out condition reports and specific interventions. Ultimately, the pieces will be ready to travel and be admired. It is fantastic to work closely with an organization like this, which takes care of the conservation and research of each piece with the best possible means.”

A look behind the preparation of a condition check

Our exhibition Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools at the Denver Art Museum is getting closer! However, preparations for such a large-scale project involve a lot of work. Our colleague Laura Geudens is happy to take you behind the scenes.

“As I have a conservation and restoration background, I support my colleagues in reviewing the condition reports for this exhibition. Before an artwork leaves for an exhibition, it is subjected to an extensive condition check. Based on that, I examine whether the condition of the work corresponds to the expectations. For me, it was particularly interesting to examine and document the collection of silver objects. These pieces are travelling for the first time and thus received a completely new condition report.”

“An example of this is A Silver Relief with the Temptation of Christ, a silver plaque forged by Arent van Bolten (1573-1633). Damage views were drawn up of the piece, which are images showing with a colour code the main damages and points of interest. Based on these images and for the exhibition’s purpose, the specific needs of the objects are determined. For this piece, it was decided to apply a felt layer to the contact points between the support and this object, allowing the piece to be displayed vertically safely.”

How do we date wood?

This month, we had the honour and pleasure of welcoming Dr Andrea Seim to The Phoebus Foundation’s art conservation studio. With her exceptional knowledge and research in dendrochronology – the scientific method of dating annual rings of trees (also called growth rings) to the exact year in which they were formed – Dr Seim is able to date and identify the wood used in paintings on panel.

During her stay, Dr Seim examined the wood from the panel Virgin with Child and Two Putti in Floral Wreath (c.1600) by Andries Daniels ( active 1599-1602) and Ambrosius Francken I (ca. 1544/1545-1618). For the occasion, she expressed her interest in different research methods, pointing out the importance of documentation and research on environmental and climatic changes around the world. These historical changes are an important anchor point in the analysis of historical and archaeological wood. In addition, she explained the new developments in dendrochronological research. The Phoebus Foundation was delighted to facilitate this visit with a small workshop on wood research.

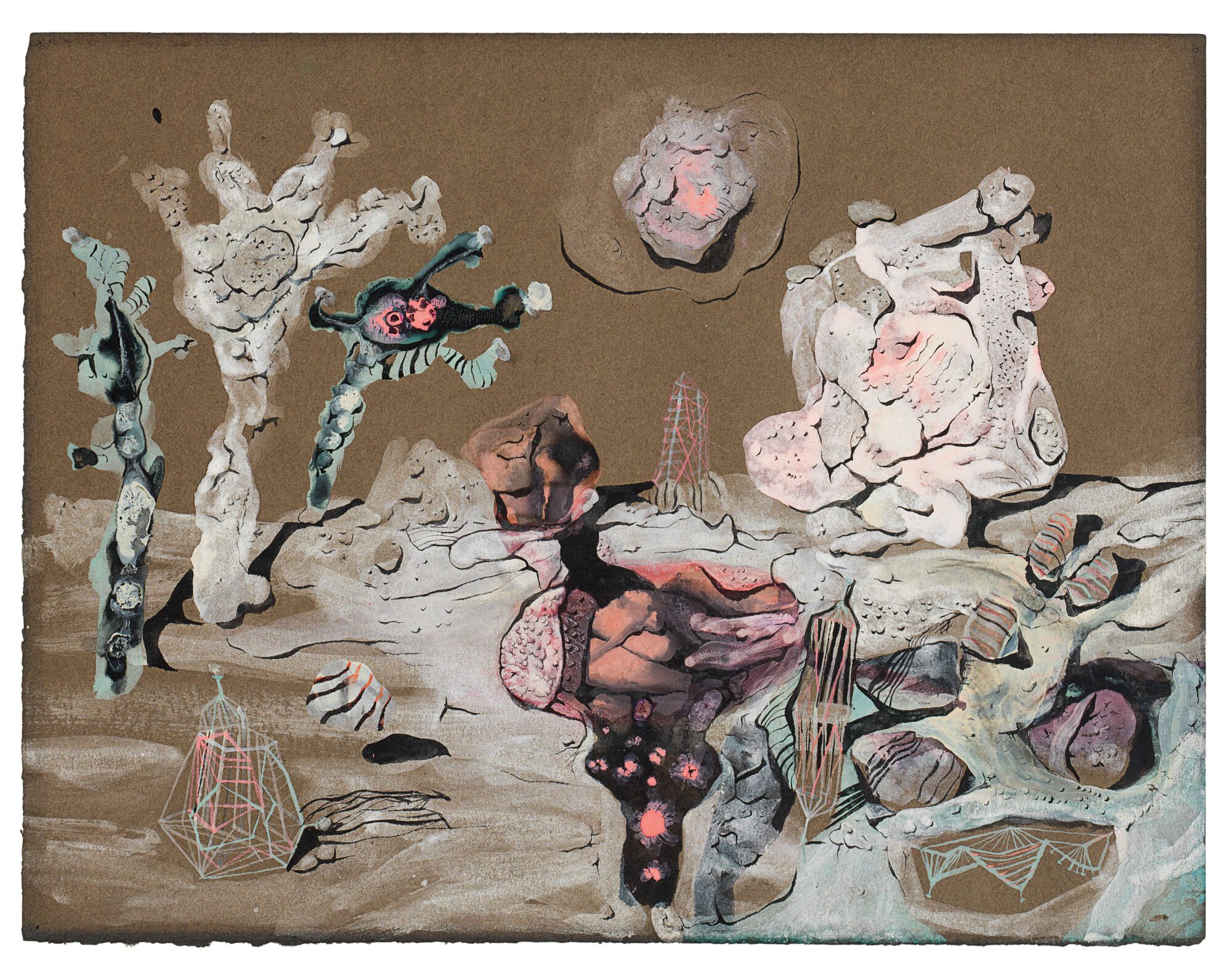

Discover the neon paint layers of Roberto Matta

Our sub-collection of Latin American art is also undergoing conservation treatments! Phoebus Conservator Naomi Meulemans is happy to take you behind the paint layers of Amorphous Figures by Chilean artist Roberto Matta (1911-2002).

“Matta created this painting in 1940, at the beginning of a pioneering period in his career. Not only his surrealist artworks but also his original choice of materials made him a progressive modernist. Did you know that he even used fluorescent pigments for Amorphous Figures? Before the Second World War, this was very unusual in the art world! Research shows that he not only added the pigment for an aesthetic, illuminating effect but also to give deeper meaning to the artwork. The painting lights up when exposed to UV (ultra violet) light and lets the underlying figures flicker.”

“In 2016, together with Conservator Giovanna Tamà, I investigated the ageing characteristics of the fluorescent pigment, with quite a dramatic result: after fifty years, the paint samples showed clear signs of ageing and after one hundred years, the fluorescent effect would even have varnished completely. Obviously, we want to avoid this! Therefore, it is important to protect the artwork against strong UV radiation. We opted for an adapted retouching method and a special frame. In order to protect the fluorescent layers but still be able to admire them from time to time, we installed a light switch on the frame to provide the artwork with controlled UV light when necessary. Doing so, we also created a surprising effect for the spectator!”

Take a look at our loans

You may have noticed… Our loan activities do not stand still! Moreover, ever since the end of the (worst) Covid-19 pandemic, we have a particularly large number of artworks that are leaving our warehouse on a short or longer journey to be presented in Belgium and abroad. Fortunately, Collection Consultant Katrijn Van Bragt and Conservator Anke Van Achter are there to keep everything on track!

“From Los Angeles to Mechelen, from Old Masters to alabaster sculptures, … The variety of works of art that are requested on loan is enormous! The institutions that call upon our collection are also extremely diverse: from historic churches to ultramodern museums. Each loan request therefore requires a unique approach.”

Conservator Carlos González Juste is taking care of Susanna and the Elders by Jan Massys

“First, we consider whether the requested artwork is available during the demanded period of time and whether the object may travel and be presented in the institution. After all, everything depends on the fragility of the object and the circumstances of the venue. Is the exhibition space airconditioned and safe? Does the artwork require additional transport or installation requirements, such as a climate box or shock-absorbing crate? Some works even get a full conservation treatment so that they are perfectly ready to be exhibited.”

Saint Barbara and Charles V in their custom-made packaging

“After all agreements with the borrower and the transport company are final, we draw up an extensive condition report. Once the artwork is packed and loaded into the truck, the journey can start!”

Meet our Phoebus Fellow: Alexandra

Meet our new Phoebus Fellow: Alexandra Taylor! All the way from New Zealand, Alexandra joined our conservation team last month. She will assist our conservators in various projects for the next three months.

Alexandra immediately started with the treatment of Jan Miel’s Figures Feasting at a Fair in Prati, outside the Walls of Rome, with the Basilica di San Pietro and Monte Mario beyond. This painting was commissioned by Marchese Tommaso Raggi (1595/6-1679) in Rome around 1650.

‘The analysis and technical research which precede a conservation treatment really fascinate me! They are the ultimate way to get closer to the master and discover his materials and techniques. These are skills I would like to develop further. The Phoebus Foundation is strongly committed to these analyses, so it is a great opportunity for me to collaborate in the Phoebus studio for a few months. Thanks to infrared reflectography, for example, I discovered inscriptions and pentimenti in Jan Miel’s painting, which are barely visible with regular light and therefore much harder to understand!’

‘The restoration treatment is not a piece of cake! Not only do we need to remove dark layers of varnish and overpaint, we also need to tackle the canvas completely. The painting will look so much more colourful and stable after the treatment!’

Curious about the final result of Alexandra’s work? Keep an eye on our website, newsletter, Instagram and Facebook!

Behind the scenes with Dymphna

Crazy about Dymphna opened a month ago in Geel! Project coordinator Niels Schalley is happy to tell you more about the construction and installation of this fascinating exhibition:

“After a two-year delay because of Covid-19, it was fantastic to finally be able to bring the exhibition to the Saint Dymphna Church in Geel. We were eagerly looking forward to the installation of the Dymphna altarpiece in this unique setting. Thanks to the Crazy about Dymphna exhibition in Tallinn, we had already carried out the entire set-up once before and therefore, we were confident that everything would go smoothly.”

“After a two-year delay because of Covid-19, it was fantastic to finally be able to bring the exhibition to the Saint Dymphna Church in Geel. We were eagerly looking forward to the installation of the Dymphna altarpiece in this unique setting. Thanks to the Crazy about Dymphna exhibition in Tallinn, we had already carried out the entire set-up once before and therefore, we were confident that everything would go smoothly.”

“In tegenstelling tot de locatie in Tallinn, de ontwijde Niguliste kerk, is de Sint-Dimpnakerk nog wel actief. Dit is een enorm voordeel aangezien het Dimpna-altaarstuk op die manier huist tussen de vele verborgen kunstschatten in een van de mooiste kerken van Vlaanderen. De acht panelen van het altaarstuk zijn zo opgesteld dat ze een echte ommegang vormen. Bijhorende sokkels met video’s vertellen razend interessante weetjes en emotionele getuigenissen. Op die manier ontluikt het verhaal van de heilige Dimpna in al haar glorie en facetten.”

Curious? Book your ticket now for only one euro!

Conservation treatment of Jordaens’ Christ Triumphant

Conservators Titania Hess and Laura Guilluy take you behind the scenes of the Phoebus conservation studio!

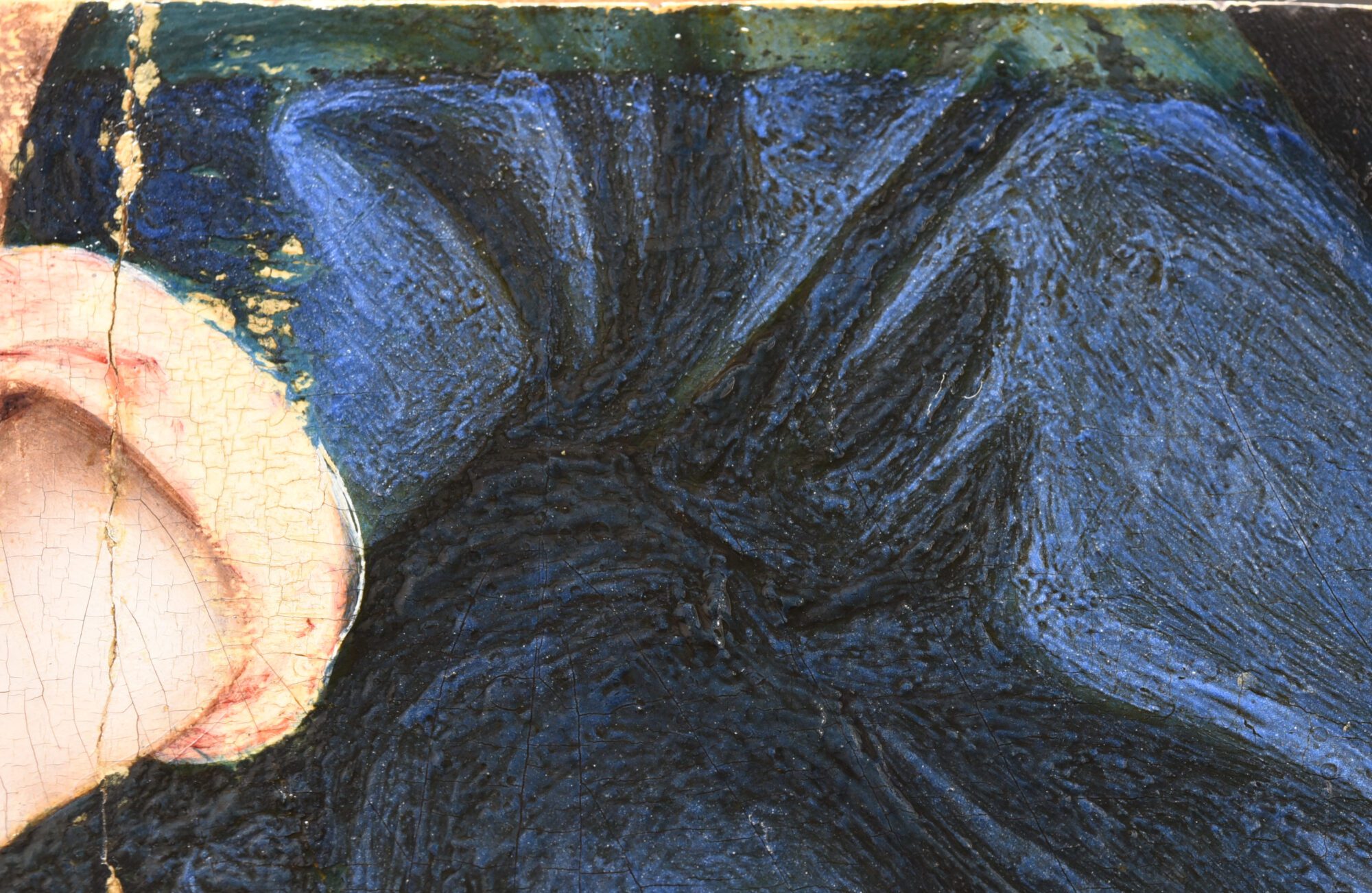

‘Christ Triumphiant, by Jacob Jordaens, has undergone a full restoration treatment! As the painting was relined during a previous treatment, the canvas was in excellent condition. Therefore, the treatment consisted mainly of the removal of oxidized varnish and encrusted soil. With gentle solvents and aqueous gels, we managed to reveal the original paint layer and its astounding palette. A few retouches and two layers of varnish were the final operations to our conservation treatment.’

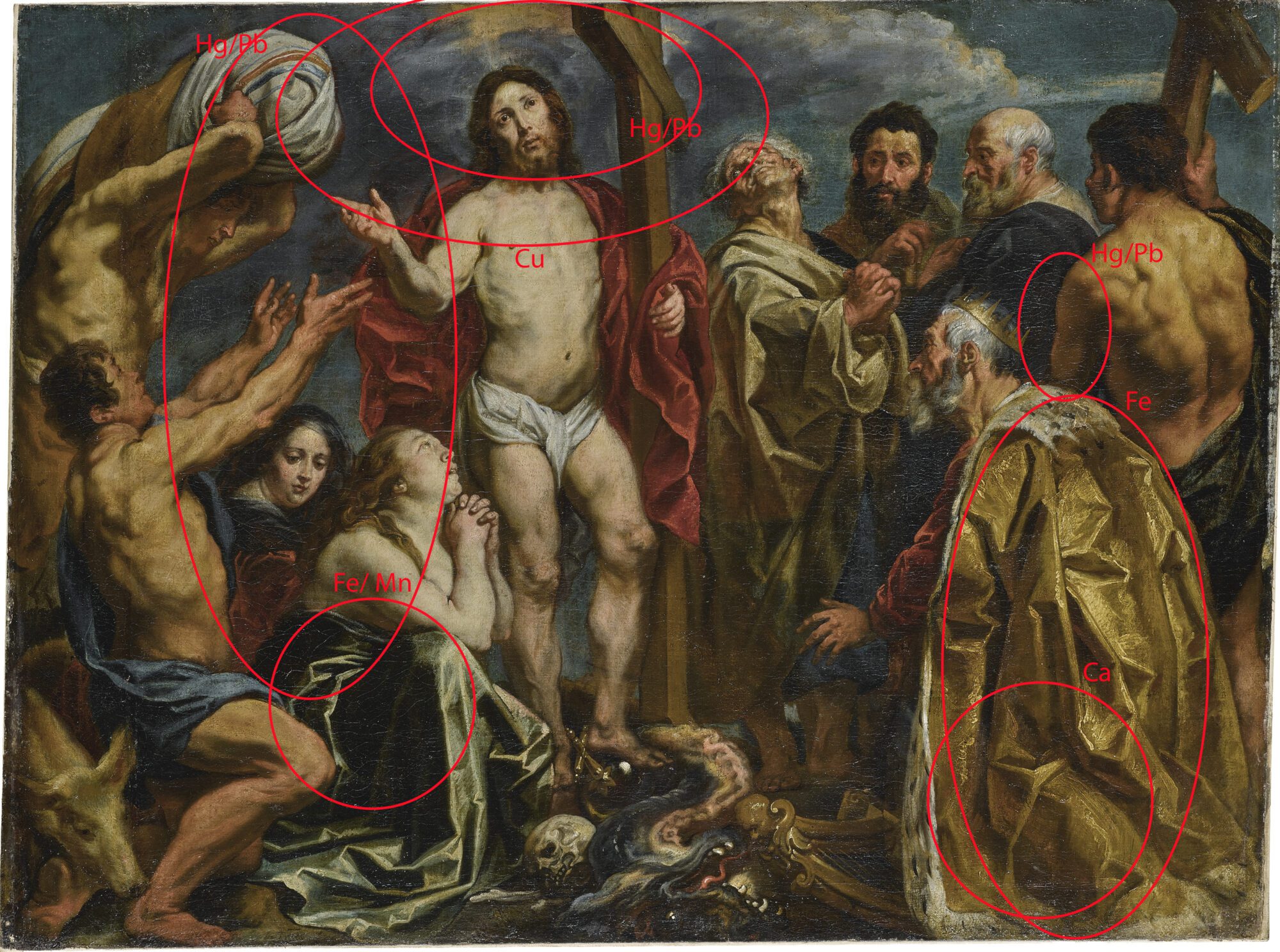

‘Prior to this treatment, the painting was subject to an intensive research, realised by Phoebus head conservator Sven Van Dorst. Using technical analysis such as Ma-XRF scans, various changes in the composition were discovered probably due to changes in the sizes of the canvas.

It turned out Jordaens painted a first composition on a less wide canvas! After a time, the Antwerp master enlarged the painting so he could realize the final composition. This enlarging of the canvas has already been observed in other paintings attributed to Jordaens, which are part of The Phoebus Foundation collection. The observation of these paintings was crucial in understanding the technics of the Antwerp great master.’

Conservation treatment of Los Muñecos

We start this new year with launching exciting conservation projects at the Phoebus conservation studio! Naomi Meulemans, conservator of the modern and contemporary sub-collections, oversees the restoration campaign of the installation Los Muñecos, created in 1960 by Italian-Argentinian artist Libero Badii (1916 – 2001).

Los Muñecos or The Dolls is an impressive installation of 14 wooden painted sculptures of almost 5 meters high. The instability of the wood and the drastic flaking of the paint layer demand an extensive restoration treatment.

Each doll bears a title that refers to a social personification. Just like our social connections in society, the sculptures are connected to each other in space by a cable. Moreover, they are also attached by a ‘Tablero’, symbol for the wheel of fortune.

Conservator Naomi started this campaign already in 2017, with a preliminary study in collaboration with collaboration with conservator and contemporary art specialist Frederika Huys. Additionally, a material analysis was performed in the studio. With surprising results: x-ray photography showed that the current damage is partly a result of the manufacturing process! Together with conservator Giovanna Tamà and the Royal Institute for Art Heritage (KIK-IRPA), the final conservation and research will be executed throughout 2022.

Stay tuned for the result!

Discover the secrets of The Virgin of the Candlelight

As usual at The Phoebus Foundation, conservation and research go hand in hand. A beautiful example is The Virgin of the Candlelight, an anonymous Peruvian work on canvas from the 18th century which is part of the collection Latin-American art from the Colonial period. Conservator Carlos González Juste offers a glimpse behind the scenes of the research and conservation of this remarkable painting!

‘Due to the thinness of the paint layer, it was already visible to the naked eye that there might be a previous painting underneath the current composition. Technical studies (IRR photography, x-ray images, MA-XRF scanning and wood analysis) have confirmed our suspicions and have revealed the existence of a completely finished painting underneath!’

‘With the conservation treatment and research of The Virgin of the Candlelight, we not only try to preserve the physical integrity of the artwork and recover its original colourful and delicate appearance. We also increase our knowledge about the techniques, materials and habits of the 17th and 18th century painting practices in Peru.’

Behind the scenes of the Ensor exhibition in Mannheim

For the exhibition James Ensor in Kunsthalle Mannheim (DE), conservator Naomi Meulemans travelled in 2021 as a courier to Germany to help with the installation of no less than 5 artworks that The Phoebus Foundation gave in loan for this project.

The work of the Belgian artist James Ensor (1860-1949), the famous “painter of masks”, is deeply rooted in the history of the Kunsthalle Mannheim. As early as 1928, the painter was celebrated there in a solo exhibition as an important contemporary exceptional artist. The exhibition in Mannheim focused on Ensor’s famous self-portrait-mask-death-still life motif, which claim an important place in his oeuvre.

The restrictions due to Covid-19 made it quite a challenge for our courier to attend. Naomi, however, managed to oversee the installation of all 5 artworks and made sure that the climate in the museum rooms was controlled correctly – an absolute requirement for these valuable and fragile artworks.

Dive behind the paint layers of Joos Van Cleve

Phoebus Fellow Anna Rota (IT) is happy to offer you a glimpse behind the scenes of her conservation project at The Phoebus Foundation:

‘Despite its small size (25 x 25 cm), this painting by the studio of Joos Van Cleve (1485-1541), immediately attracts our attention. The unusual diamond-shaped support seems to be unique in the artist’s oeuvre and raises questions about the distribution of diamond-shaped paintings in Renaissance painting.’

‘The facial tones, with such a soft transition between light and shadow, can be compared to Leonardo Da Vinci’s “sfumato.” The artist was particularly attentive to detail and used various material tricks: just look at the thickness of the colour layer of the pearls in Mary’s hair or the folds of the white veil along her neckline. Mary’s hair and the faces and hands, on the other hand, are rendered with very thin brushstrokes.’

‘The removal of varnish and retouching has brought back the beautiful colors of the facial tones, as well as some details that were previously less visible. The conservation treatment has allowed us to discover more about the painting technique of Van Cleve and his studio.’

Discover the project of Phoebus Fellow Anne-Rieke

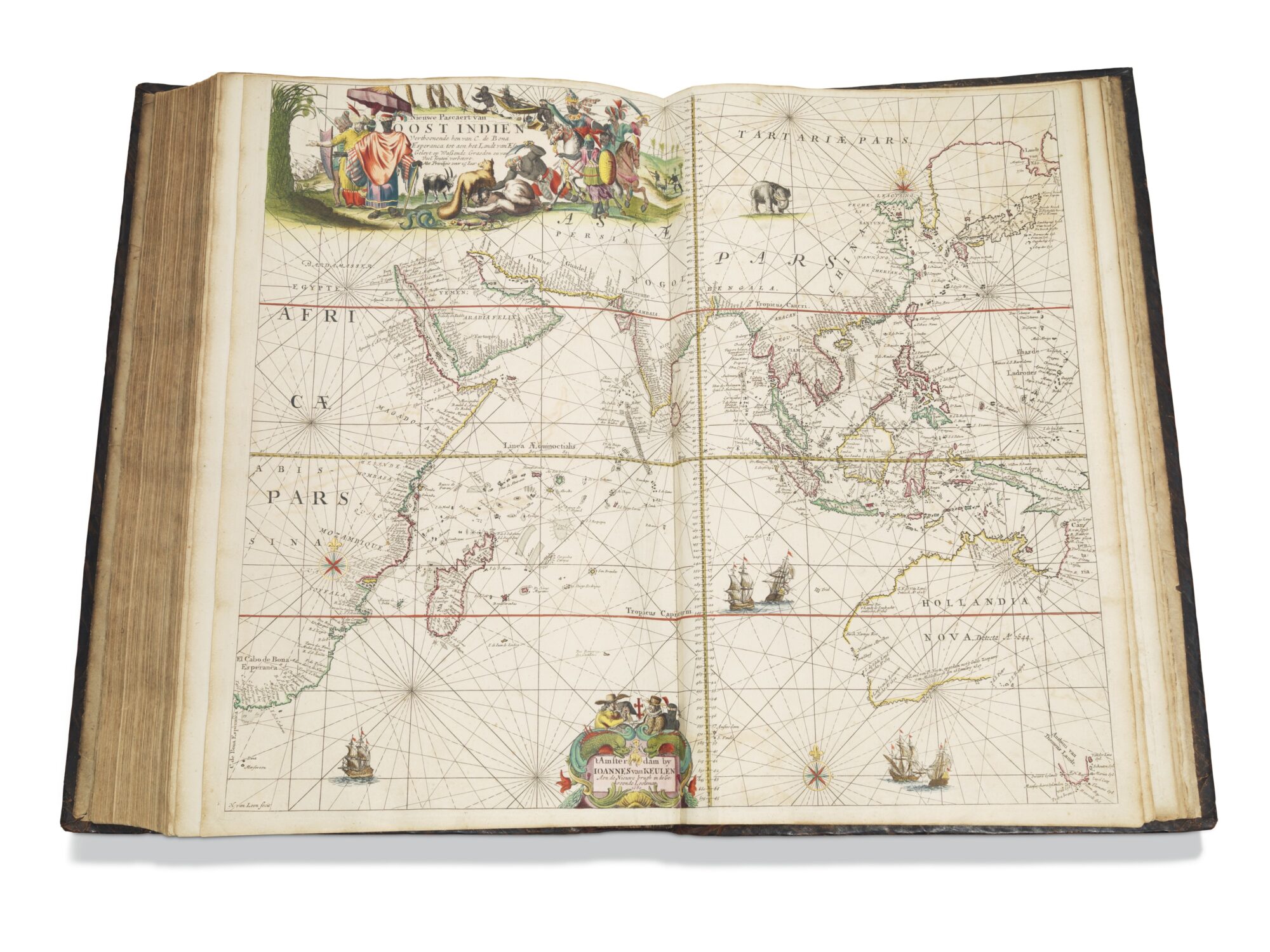

Art historian Anne-Rieke van Schaik (NL) focused during het fellowship on the sub-collection Topography and Cartography. Anne-Rieke is glad to give an insight in her Phoebus Fellowship program:

‘Early modern media, the narrative qualities of cartography, and the intertwining of maps, books and prints in this period are really my cup of tea. As member of the Explokart Research Programme on the History of Cartography (University of Amsterdam) I am working on various projects such as a specialized database and a handbook of historical cartography.’

‘During my Phoebus Fellowship, I examined the wide variety of objects in the rich Topography and Cartography collection of The Phoebus Foundation; ranging from sea charts, military news maps, cityscapes and early world maps to colored atlases, travel books and globes. My job was to perfection the inventory of the objects and to improve the catalog descriptions. The striking research results and treasures of the collection will be made accessible to a wider audience later on, for example in an exhibition or publication.’

Goodbye, Tallinn!

Time flies! After more than seven months, we said goodbye to the city of Tallinn at the end of November 2021, where we organized the exhibitions From Memling to Rubens and Crazy about Dymphna at the Kadriorg Museum and the Niguliste Museum. It was such an honour to travel abroad for the first time ever with our extensive collection of old masters! We are extremely grateful to our partners in Estonia for this unique opportunity. Due to their great success, both exhibitions were extended by one month so that visitors could enjoy these masterpieces even longer. At the beginning of December 2021, the team of The Phoebus Foundation travelled to snowy Tallinn to supervise the dismantling of the exhibitions and to bring all the art works back home.

Take a look through the lens of our photographer

Collection registration and beautiful books don’t exist without perfect images. Take a look behind the scenes of our photo studio where our photographers capture various artworks with their lenses. Michel is happy to tell you more about this fascinating and challenging task.

Is there a great difference between the photography of artworks and other photographical genres?

‘Fine art photography really is a specialization. Most people think we just put a painting or sculpture in front of a white fond, we press a button and that’s it. It’s not that easy in reality. The photography of artworks is very technical because of the large diversity of objects. A glass vase, a manuscript or a painting each demand their own setting and lighting. Moreover, they need to be adjusted over and over again during the photoshoot. In fashion photography for example, the lighting is fixed and the model tries different poses to get a perfect picture. In art photography it’s the photographer who needs to play with light and shadow because the object doesn’t move obviously! (laughs). It’s always a new puzzle that needs to be solved.’

Where does your specialization and fascination for fine art photography come from?

‘By accident! One of my first jobs was the photography of two terra cotta vases of the Dominican Republic for an advertisement. I have been photographing for various institutions and projects ever since. After all these years, it is still an enrichment for me. The variety of objects I get to see through my lens is extraordinary! I also get the chance to have a close look at the artworks and I often discover remarkable details.’

Which type of object do you like the most?

‘Definitely sculptures. In most cases, every side of the artwork has been embellished as if the sculptor wants you to walk around. As a photographer I always try to find the best angle in order to display the sculpture as vividly as possible. It really is an experiment with light and shadow.’

A glimpse behind the scenes of our Maritime and Logistic Heritage Volunteers

Discover a very special part of The Phoebus Foundation’s collection: Maritime and Logistic Heritage! A team of enthusiastic volunteers is in charge of the daily routine of this extraordinary collection. As retired dockworkers with a passion for heritage they know this collection of historical risers, tractors, trucks, and measuring and weighing devices like the back of their hand. Every week, the group gathers together in the warehouse Argentin in the northern part of Antwerp to work on the conservation and the accessibility of the collection.

For some of our volunteers, a port heritage day already starts before dawn. Early bird Juul is always out and about at 6 AM. One after another, colleagues arrive and join the group. Around 8:30 AM there is a small meeting to discuss the daily schedule whilst enjoying a cup of coffee. All volunteers have their own unique background and expertise which makes everyone an essential member of the team. Juul and Roger are specialists in welding; Freddy knows all the secrets of tinkering and electrotechnics is Fred’s cup of tea. This diversity makes it possible to work on multiple large projects at the same time. An important element of their tasks is also the conservation of rare heritage objects. “The current major project we are working on is the Antigoon crane”, Fred explains. “It is a port vehicle of the early fifties and probably the last example left of its type. With lots of patience and effort, we managed to complete the mechanical work. It certainly wasn’t a piece of cake because we didn’t have a single plan or piece of documentation. Luckily we could count on the craftsmanship and expertise of our team members to solve these problems together.”

In small groups, the volunteers diligently continue their work. Painting, sanding, welding, restoration of all possible tools,… before you know it, it is time for a well-deserved coffee break where our volunteers share their memories from ‘good ol’ times’. “This is very important to us”, Harry, the youngest of the group, explains. “After retiring as commercial manager in the port industry after 43 years, I am grateful I could become part of this team. I have always been intrigued by history and I am happy I can contribute to the Logistics and Maritime Heritage here. Even though I don’t have a lot of technical expertise, I can cooperate in the large valuation project of the collection. We make sure every object is measured, catalogued and photographed. Some pieces are truly unique and have an extraordinary history, which always fascinates me. The many stories and interesting anecdotes bring the items back to life.” The other volunteers share the same passion and motivation.

The team has completed many large conservation projects throughout the years. This is essential to volunteer Martin. “Our aim is to preserve the maritime heritage for future generations. The Antwerp port and her workmen are world famous because of their craftsmanship and professionalism. Sadly, this history is getting lost rapidly. The generation of whom I learned the tricks of the trade is now between 75 and 91 years old. Acts and tools from back then are no longer in use. Therefore, it is our task to pass on this important heritage to the future generations. We hope to realize this with our efforts in the Argentin warehouse.”

Until 12 PM the team collaborates on various port heritage projects. Then, it’s time for a well-deserved lunch. Volunteer Jacques, who has been a ship’s cook for years, often surprises the team with soup or a home-cooked meal. Old memories and various port anecdotes are shared around the table. Together, the volunteers dream about the future. “Hopefully, we can reopen our doors for group visits soon. This way, we can share our passion and moreover this exceptional collection with a broad audience again.”

Conservation treatment of the oldest oil painting in our collection

Take a look behind the scenes at the restoration treatment of one of the oldest oil paintings from the collection of The Phoebus Foundation. Dating from c.1418-25, the artwork is even older than the famous Ghent Altarpiece by the brothers van Eyck (1432). Consisting of four panels, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, it was probably originally part of a larger altarpiece.

If you look closely, you can see that the artist was already very progressive by casting shadows on his figures, giving them a three-dimensional character. However, a technical cast shadow is still missing, which indicates that we are at an important turning point in Western art history. For this reason, we recently decided to start an extensive conservation treatment. During the treatment we hope to learn more about the geographical origin of the panels and about the methods and materials used by the painter.